Art Photographers

On This Page

Seeing and understanding the work of master photographers shows us what is possible with the medium. Of course, what is possible today wasn’t always the case. In the earliest days of the medium, a variety of constraints held photographers back.

Some limitations were technical. The processes of the mid- to late nineteenth century were rather complex and cumbersome even compared to what followed a half-century later. The available equipment was mechanically and optically crude. Photographers carried the burden of handling and mixing raw chemical ingredients many of which were hazardous to one’s health. All of this limited what photographers could accomplish.

By the 1890s, however, things began to change. Wet glass plates gave way to dry plates and film. The speed of emulsions increased. The optical quality of lenses improved, and handheld box cameras freed photographers from their tripods. And the availability of commercial developing and printing services all aided the expansion of the practice of photography and the kind of subject matter photographers captured in images.[1]

Beyond technical limitations, however, another far more important factor restrained the evolution of the medium: reluctance to accept photography as a form of art.

The Challenge: Establishing Photography as Art

Since photography’s emergence in the middle of the nineteenth century, those who were active in the world of art debated whether or not a mechanical device like a camera could make art. Early proponents faced a steep challenge. Gustave Le Grey, Julia Margaret Cameron, Peter Henry Emerson, and many others had broken new ground by the end of the nineteenth century. Yet in the eyes of most artistic observers, photography simply did not exist on the same plane as painting or sculpture. Instead of collecting or exhibiting it, museums largely ignored photography, and they refused to accepted it as a legitimate artistic medium.[2]

Compounding matters was the widespread use of photography for non-artistic purposes. The invention of dry plates and the development of faster shutter mechanisms allowed faster exposure times. Photographers could now go anywhere and record anything. The medium proliferated in a multitude of applications. In the minds of some critics, newspaper and magazine images and picture postcards cheapened photography. With its famous advertising slogan, “You press the button—We do the rest,” Eastman Kodak brought photography to the masses.[3] Images were suddenly everywhere.

How could one take a medium that allowed the proliferation of such dreck and use it to make art?

To counter the idea that photography was simply a pursuit for the masses, advocates established organizations for promoting the medium’s acceptance as fine art. The Wien Kamera Klub (Vienna Camera Club); the Linked Ring in London; the Photo-Club de Paris; and the Berlin, Munich, and Vienna Secessions all had international memberships, mounted exhibitions, and published journals centered on photography.[4]

The dominant aesthetic among these groups was Pictorialism. As a counter to cheap newspaper, postcard, stereoscope, and snapshot images, Pictorialist photographers attempted to replicate a painterly aesthetic in their work. They often rendered their subjects out of focus and on rough, highly textured paper.[5]

Although the Pictorialist movement helped gain photography acceptance as a form of high art, its reach across time was short.

Early Modernists in America

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946)

In America, Alfred Stieglitz did the most to organize a network of like-minded photographers than anyone else in Europe. With the help of Edward Steichen and Alvin Langdon Coburn in 1902, he founded the Photo-Secession, a marked break from the dominant style of amateur photography societies of the time and an assertion of the spiritual expression of the artist himself over the mimetic nature of some photographic practitioners. Also in 1902, Stieglitz also began publishing the highly influential journal Camera Work, which remained in print until 1917. And in 1905, he opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue, a place that was known simply as Gallery 291.[6]

Although he drew inspiration from the Pictorialist movement at first, Stieglitz dispensed with Pictorialism over time. In 1904, art critic Sadakichi Hartmann called for “straight photography,” a rejection of Pictorialism’s gauzy aesthetic. Stieglitz eventually shifted his own focus to practicing photography using this approach. Using his considerable position at the center of the art world in America, he also promoted the work of other modernists.[7]

In Alfred Stieglitz’s own photography, one can see a gradual movement away from the airy and gossamer aesthetic of Pictorialism. With “The Terminal” (1893), Stieglitz demonstrated a move toward a harder-edged realism in subject matter and approach.[8] I also see this photograph as a very early example of street photography—after all, it is an image that depicts a candid view of a street scene, albeit one well over a century old.

Another of my favorite photographs by Alfred Stieglitz is “From the Back Window—291” (1915). Taken from a back window of his art gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue in New York, it’s a compelling example of nighttime urban photography after a fresh snowfall.

The thing I admire most about Alfred Stieglitz’s many accomplishments is the way he operated at the center of the art and photography world in America. In any reading of the history of early twentieth century art, one doesn’t have to wait long before encountering his name and the way he was connected to an incredibly large number of photographers both old and young.

More information:

Edward Steichen (1879-1973)

One photographer who figured prominently in Stieglitz’s Camera Work was Edward Steichen, who was that publication’s most frequently published and discussed photographer.[9]

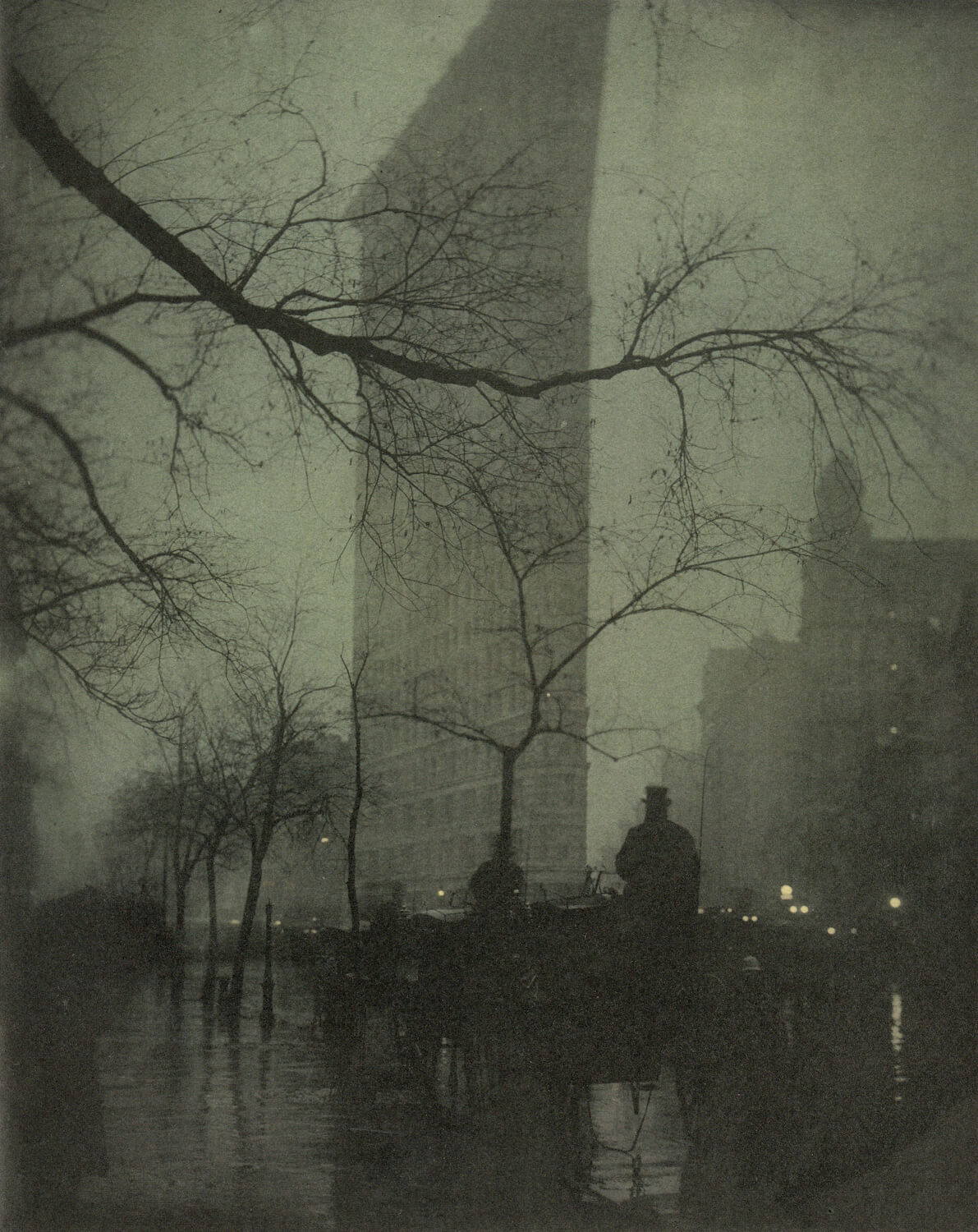

In his earlier years, Steichen blended techniques from painting and photography.[10] Among all of his works from this time period, my favorite is “The Flatiron” (1902), which superbly renders a dreary early evening next to Madison Square Park in Manhattan. I love its moody quality.

Although Pictorialism helped define his career’s early work, Steichen’s service as a war photographer in World War I changed all that. Horrified by what he had seen, Steichen resolved to make art that reflected the new age. Across a wide range of genres—fashion photography, celebrity portraits, still lifes, and commercial advertising photography—he shifted markedly to a kind of precision that was absent in his earlier photography.[11]

In the end, Steichen’s position as director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York marked the medium’s acceptance as a legitimate form of art, one that could still be appreciated by the masses. In particular, his 1955 exhibition Family of Man emphasized the commonality and universality of humanity over political polarization and other divisiveness. The book that came out of it was the best-selling photography book of all time.[12]

More information:

Paul Strand (1890-1976)

Another photographer in Alfred Stieglitz’s network was Paul Strand. In 1909, he completed his studies at the Ethical Culture School under noted documentary photographer Lewis Hine, who introduced him to Stieglitz. Since the age of seventeen, Strand had been visiting Gallery 291. Eventually, he befriended Stieglitz and many other artists whose work appeared at the gallery.[13]

At first, Strand had been producing work characteristic of soft-focus Pictorialism. But with Stieglitz’s urging and under the influence of Cubism, he shifted his approach and began producing sharper and more abstract photography. Stieglitz heartily approved of Strand’s movement toward modernism. He described Strand’s work as “brutally direct.” In fact, he devoted the final issue of Camera Work in 1917 entirely to Strand’s work.[14]

Among all of Paul Strand’s works, his “Wall Street” (1915) is by far my favorite. The daunting void of blackened window recesses that tower over the passersby on the sidewalk below demonstrates Strand’s adoption of abstract modernism and help underscore the commentary he was making about his subject.

Paul Strand’s social consciousness continued later into his career. In 1936, he helped establish the Photo League, a cooperative of photographers bound together by a variety of social and creative causes.[15]

More information:

Edward Weston (1886-1958)

On America’s West Coast in the early 1930s, numerous other photographers coalesced. Members of Group f/64 sought image sharpness from foreground to background as a result of the effects of small lens aperture (thus the group’s name). Their work was a direct counter to Pictorialism.[16] At the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco in November 1932, the group had their inaugural exhibition.[17]

Among the several members of Group f/64, Edward Weston was perhaps the best known. He moved to California in 1906 and had already established himself as a photographer by the time he met Alfred Stieglitz in New York in 1922. Like Steichen, Weston photographed a wide range of subjects including landscapes, still lifes, nudes, and portraits. He was particularly interested in capturing light, shade, and texture. Above all, he was concerned with the realism of straight photography. His motto was “presentation instead of interpretation.” Completely dedicated to his craft, Weston sacrificed emotional and financial stability to pursue photography.[18]

I still remember how struck I was upon seeing Weston’s “Pepper” (1930) in my introduction to art history textbook in college. It’s a wonderful example of Weston’s use of sharp focus, deep blacks, and silvery grey tones to convey the texture and lighting of something as simple as a pepper.

More information:

Surrealism

In stark contrast with the sharp realism of Group f/64, Surrealism offers a rather different approach to photography. There is no doubt in my mind that it has had an effect on my own practice.

André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto of 1924 declared the primacy of the irrational and a belief in truth beyond realism. Deeply indebted to Freud’s theories about the unconscious and his methods for revealing unconscious desires, Surrealism emphasized imagination over the concern for social change that was widely prevalent in post-World War I Europe. Perhaps counterintuitively for a medium that many thought was primarily objective, photography was central to Surrealism. By taking photographs particularly through unconventional techniques, one could sidestep the rational mind and explore the subconscious.[19]

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky, 1890-1976)

Although his ties to the Dada and Surrealist movements were informal, Man Ray nonetheless made significant contributions to both. One of the first abstract painters in America, he turned to photography in 1915. In collaboration with Lee Miller, with whom he had a brief love affair, he developed the solarization process, whereby light and dark tones are reversed as a result of overexposure and specialized developing techniques.[20]

Man Ray employed the solarization process in his 1929 portrait of a 22-year-old Lee Miller, which I find fascinating in technique and beautiful in form.

A lot of Man Ray’s work is just weird, and I don’t really connect with much of it. But what I like about it—and about Surrealism in general—is the way it offers another view of the world around us. Photography doesn’t always have to be about realism or a faithful portrayal of the people and places before us. Sometimes exploring the subconscious can yield something rather interesting and refreshing.

More information:

Umbo (Otto Umbehr, 1902-1980)

Perhaps not quite a Surrealist, Umbo is still worth considering under that movement’s rubric considering that his work also offered an alternate view of reality. After studying at the Bauhaus in 1921, Umbo worked as a photojournalist and artist in Germany. He was influenced by Hungarian painter and photographer and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy, and he was friends with Robert Capa, the noted American photojournalist. His photographs of large cities earned him international fame as one of Germany’s leading avant-garde artists of the 1920s.[21]

Two photographs by Umbo demonstrate his abilities. “Mysterium der Straße” (Mystery of the Street) and “Unheimliche Straße” (Sinister Street) show the view of a streetscape from above in a reimagined way.

In both photographs, long shadows in early- or late-day sunlight are larger than the persons who cast them. By using simple inversion, Umbo unsettles things by placing imagination over concrete understanding,[22] which is what Surrealism is all about.

World War II was not kind to Umbo. During the conflict, he lost his entire photographic archive.[23]

More information:

Subjective Photography

Related to Surrealism, subjective photography, was a 1950s-era movement in Germany which held the inner human psyche and a sense of disorientation as having primacy over the outer world. Partly as an attempt to separate themselves from the photojournalism and documentary photography of the time, subjective photographers sought to explore the complexities of the inner state through the experimental techniques of the Bauhaus but with a darker and edgier style.[24]

Otto Steinert (1915-1978)

Subjective photography’s chief proponent was Otto Steinert, a German doctor during World War II who abandoned medicine in favor of photography. He was interested by the prewar accomplishments of the Surrealists and the Bauhaus movement, and he sought to pick up where those two movements left off. In 1949, Steinert helped found the “fotoform” group, which, as he intended, would carry the torch of the pre-war avant-garde.[25]

Three of Steinert’s images stand out in my mind.

Each one of these photographs demonstrate Steinert’s use of a hallucinatory view of individuals moving through urban environments in an almost dreamlike, subconscious way.[26]

More information:

Harry Callahan (1912-1999)

Another exponent of the subjective photography movement was Harry Callahan. Although he came from the same generation as Otto Steinert, his experience as a young man in America was rather different from the German doctor-turned-photographer.

Callahan worked at Chrysler before studying engineering at Michigan State University. He then dropped out, returned to Chrysler, joined the camera club there, and began teaching himself photography in 1938. Two years later, he attended a talk by Ansel Adams, an experience which led him to practice photography more seriously. He made great strides in the years that followed. In 1946, László Moholy-Nagy invited Callahan to teach at the Institute of Design in Chicago. And in 1961, Callahan established a photography program at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he stayed until his retirement.[27]

His method was to go out nearly every morning and shoot numerous photographs. Later in the day, he made proofs of the best negatives from his outing. Yet by his own estimation, he made no more than a half-dozen final prints every year.[28]

Callahan tended toward detail shots which have an abstract effect. He experimented with double exposures and overexposure to create unique effects.[29]

His wife Eleanor, who he met at Chrysler, was his steadfast muse in many of his photographs.

Out of his entire body of work, I am partial towards Callahan’s Surrealist-inspired street photography. His use of unconventional techniques to depict people as they go about their day led him to produce for first-rate images.

More information:

Notes

1 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 434.

2 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 348, 390.

3 Penelope J.E. Davies et. al., Janson’s History of Art, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2011), 936, https://archive.org/details/history-of-art-janson, accessed May 20, 2025.

4 Penelope J.E. Davies et. al., Janson’s History of Art, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2011), 936, https://archive.org/details/history-of-art-janson, accessed May 20, 2025.

5 Penelope J.E. Davies et. al., Janson’s History of Art, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2011), 936-937, https://archive.org/details/history-of-art-janson, accessed May 20, 2025.

6 “Photography,” Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism, January 10, 2017, https://www.rem.routledge.com/articles/overview/photography, accessed May 1, 2025; William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 391, 394; Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 672, 678.

7 “Straight Photography,” Art Institute of Chicago, n.d., https://archive.artic.edu/stieglitz/straight-photography/, accessed December 15, 2024.

8 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 390.

9 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 391.

10 Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 650.

11 Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 650-660; William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 542-550.

12 Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002), 312-314.

13 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 478; Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 686; “Paul Strand,” Art Institute of Chicago, 2016, https://archive.artic.edu/stieglitz/paul-strand/, accessed December 5, 2024.

14 “Paul Strand,” Art Institute of Chicago, 2016, https://archive.artic.edu/stieglitz/paul-strand/, accessed December 5, 2024; “Straight Photography,” Art Institute of Chicago, n.d., https://archive.artic.edu/stieglitz/straight-photography/, accessed December 15, 2024.

15 “Paul Strand,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Strand, accessed May 1, 2025.

16 Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002), 272-274.

17 “Group f/64,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Group_f/64, accessed December 15, 2024.

18 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 489-494; “Edward Weston,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Weston, accessed May 1, 2025; Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 730-735; Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002), 278-280.

19 Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002), 257.

20 “Man Ray,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Man_Ray, accessed May 9, 2025; Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 512, 521; Marley Marius, “The Deep Bond (and Short Affair) Between Lee Miller and Man Ray,” Vogue, September 12, 2023, https://www.vogue.com/article/lee-miller-man-ray-relationship, accessed July 10, 2025; “Solarization (photography),” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solarization_(photography), accessed July 10, 2025.

21 “Otto Umbehr,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otto_Umbehr, accessed May 11, 2025; Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 709.

22 “Umbo (Otto Umbehr) | [Mystery of the Street],” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, n.d., https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265563, accessed December 16, 2024; Shira Wolfe, “Umbo. Photographer at Berlinische Galerie,” Artland Magazine, n.d., https://magazine.artland.com/umbo-photographer-at-berlinische-galerie/, accessed December 16, 2024.

23 Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 709.

24 “Subjective Photography,” Tate, n.d., https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/subjective-photography, accessed December 15, 2024; “Otto Steinert | Call,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, n.d., https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/266349, accessed December 16, 2024.

25 Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 666-667; Stacy Platt, “Consideration of an Image: Otto Steinert’s Ein-Fußgänger,” The Space in Between, April 4, 2015, https://the-space-in-between.com/2015/04/04/consideration-image-otto-steinerts-ein-fus-ganger/, accessed December 15, 2024.

26 “Otto Steinert | Call,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, n.d., https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/266349, accessed December 16, 2024.

27 “Harry Callahan,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Callahan_(photographer), accessed May 2, 2025.

28 “Harry Callahan (photographer),” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Callahan_(photographer), accessed May 1, 2025.

29 Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 87.