Documentary Photographers and Photojournalists

On This Page

In 1920s, mass media grew at astonishing pace. Berlin alone had 45 morning and 14 evening newspapers. Hundreds of magazines and illustrated journals were devoted to everything from automobiles to fashion. The term photojournalism entered the lexicon. In Germany and Central Europe during the hard interwar years, many art photographers turned to photojournalism to make a living. In America in the 1930s, Life took its cue from European models. Technical advances in photomechanical reproduction technology, 35mm cameras, safer flash bulbs as replacements for unshielded bursts of magnesium flash power, and improvements in film speed all contributed to an increasing glut of images. In response to the rise of radio, newspapers and especially tabloids competed by using dramatic pictures like the ones from the Hindenburg crash in 1937. People started to see photography as ephemera. But some publications resisted the race to the sensationalistic bottom. More thoughtful forms of newer photojournalism include the photo essay, whose content was often not time-sensitive and whose popularity persisted even after instant transmission of photographs became possible.[1]

Early Practitioners

Lewis Wicks Hine (1874-1940)

Well before the emergence of photojournalism as a distinct undertaking were trailblazers like Lewis Wicks Hine, who was an early practitioner of social documentary photography. He gave up the security of a teaching job and turned to photography to promote social reform in America during the early twentieth century. Notable was his work with the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) in 1906.[2]

Technically, compositionally, and artistically, two images of Hine’s stand out in my mind. In 1908, Hine photographed Sadie Pfeifer, a young 48-inch-tall spinner who worked in a cotton mill in South Carolina. His simple but powerful image showed the abhorrent nature of child labor to a wider audience and helped bring about meaningful reform.[3]

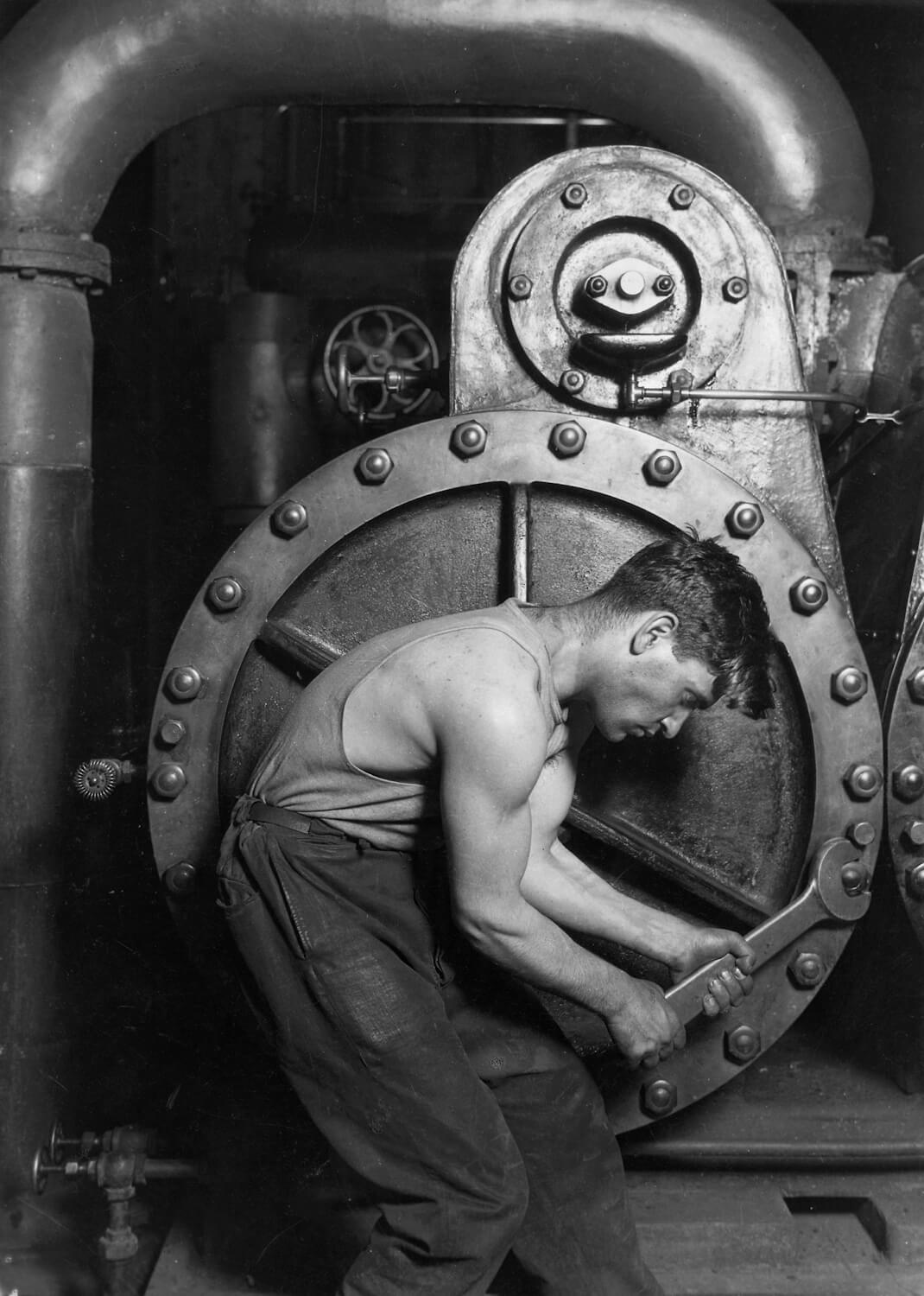

Later, Hine turned his attention to powerhouse workers. In 1920, he photographed a mechanic hard at work on—or perhaps subservient to—heavy machinery.

Both instances demonstrate Hine’s first-rate ability to capture what it must have felt like to spend one’s existence in such exhausing and soul-crushing environments.

More information:

Erich Salomon (1886-1944)

Circulating in more elegant but no less compelling environments was Erich Salomon, one of the first pioneers of modern photojournalism. With an unobtrustive Ermanox camera as his tool of choice, discretion was his forte. He worked his extensive social connections to gain access to behind-the-scenes political dealings, and he used his social graces to gain the respect and appreciation of his subjects. His candid work was highly sought after among illustrated weekly magazines. It led their readership to expect the right to see into what had been an opaque world of politics.[4]

Contrary to the pressures to produce wiz-bang photography replete with drama and sensation, the power of Erich Salomon’s photojournalism lies in its quiet candor.

A German Jew, he fled to the Netherlands as the Nazis came to power. He was ultimately captured by German forces and sent to Auschwitz, where he and his wife died in 1944.[5]

More information:

The Great Depression

During the Great Depression in America, documentary photography became far more tightly defined as a genre with a focus on depicting others as “people like us.” At the Resettlement Administration, which was formed in 1935 and which reorganized as the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in 1937, Roy Stryker supervised the photographic activities of these federal agencies and helped create one of the most powerful records of this period in history.[6]

Walker Evans (1903-1975)

One of Stryker’s first hires was Walker Evans. Influenced by Eugène Atget,[7] who wandered around the streets of Paris and surrounding areas with a camera during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Evans discovered a love for photography at the end of the 1920s and abandoned his earlier intention to be a writer.[8]

With a large format camera, Evans took a formalist approach while also using a 35mm camera for candid shots of everyday subjects. An austere man, Evans mistrusted political or social groups, slogans, and agendas. He disliked modernist abstraction and instead favored socially-committed documentary photography.[9]

Perhaps my favorite Walker Evans photograph is his image of a roadside stand near Birmingham, Alabama, in 1936.

As I was finishing graduate school, I encountered the Library of Congress’s Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection for the first time. Evans’s image was among my favorites. There was obviously great pride among those who operated this stand, and Evans conveys that in this photograph.

More information:

Dorothea Lange (1895-1965)

Largely in response to the growing hardship around her, Dorothea Lange shifted from art to social documentary photography in the early 1930s. In 1935, economist Paul Taylor hired her to help create a report on migratory labor. The project’s approach, which used a combination of statistics, social science, and photography, would become a model for Farm Security Administration and other such future efforts in the decades to come.[10]

My favorite Dorothea Lange photograph is one entitled “Tractored Out” (1938).

With a derelict and abandoned farm house sitting in the background, we see leading lines which draw our eye to it and which underscore its loneliness. Late afternoon or early morning light casts its shadow across the valleys of plow troughs. The irony of the house sitting in the middle of a plowed field raises the question in the viewer’s mind about what happened to the inhabitants of the house. Did they get pushed out? Did the land surrounding the house get gobbled up by the increasing mechanization of farming?

More information:

Life Magazine

During its golden era from the 1930s to the 1960s, Life magazine published a kind of photojournalism and visual storytelling that endures as a powerful record of the period.

Margaret Bourke-White (1904-1971)

Margaret Bourke-White began her career in 1927 as an industrial and commercial photographer with a modernist approach. She made dramatic use of perspective, light, and shadow on hard industrial edges. By the mid-1930s, she had shifted to more of a candid social documentary style. In 1936, Henry Luce hired her as one of the first four staff photographers for his new magazine, Life. The publication was a phenomenal success. Working for the magazine came to be considered the pinnacle of photojournalism, and she was one of the most respected photographers there.[11]

“Two Tractors Plowing” (1954) is but one example of her first-rate work.

In this photograph, we see a bold aerial abstraction of a rural setting. The subject is clearly the patterns being made by the two tractors captured on the edge of the plowing.

More information:

Alfred Eisenstaedt (1898-1995)

Another of Luce’s original four staff photographers for Life magazine was Alfred Eisenstaedt. After emigrating from Germany to America in 1935, he began working with Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, and Town and Country shortly thereafter. Eisenstaedt’s images of people did the most to earn him a place in the history of photography.[12]

Setting aside his better-known work—think for instance of that ubiquitous image of an American sailor kissing a nurse in Times Square upon Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II—I find that Alfred Eisenstaedt’s more understated candids are far more interesting.

At the top of my list is a photograph he took at a puppet show in Paris in 1963.

Rather than shoot the photograph from behind the audience looking forward, he positioned himself in front with the puppet show to his back. He captured the climactic moment with all manner of expressions on the faces of the children in the audience. This is one of my all-time favorite photographs.

More information:

Andreas Feininger (1906-1999)

Roaming the streets of New York when not on assignment, Andreas Feininger worked as a staff photographer for Life magazine between 1943 and 1962. Later, he continued his work as a photographer and expanded his activities as a writer.[13] Indeed, Feininger was a precise and rather prolific author whose contribution to photography went well beyond the images he created.

Feininger demanded that a photograph should have something to say to the viewer. It should be able to stand on its own and tell its own story without a lot of supporting text.[14]

In both his photographic technique and his style of writing, Andreas Feininger’s work possesses a level of precision that I admire. Perhaps lacking a kind of human warmth that makes the work of other photographers come alive, Feininger’s photography has a great deal of power nonetheless. It effectively uses perspective to convey a sense of what he must have felt when he experienced those expansive landscapes or those close-up objects he photographed.

One excellent example of Feininger’s street photography is his 1945 photograph of rush hour in New York.

Rather than use a wide-angle lens to capture the enormous buzz of activity around him, Feininger selected a telephoto lens to compress near and far and to add an energetic sense of density. Feininger captured what it must have felt like to experience that environment first hand, something I try to keep in mind when I have a camera in hand.

In 1948, Feininger shot a depressing scene filled with oil rigs in California.

In this photograph, we see another instance of Feininger’s use of perspective to capture the feeling of another kind of environment. Seeking to add a sense of both ugliness and grandeur to the scene, Feininger himself said that he:

did that deliberately because that way, people remember what oil stands for, what this pursuit of oil does to the environment. I had to go pretty far back to find the perspective that puts all these derricks close together. That is how I got this feeling of their importance and their dynamic and their horror. They have totally ruined the whole landscape as far as you can see... It is dead, totally dead.[15]

When I was in college, I bought and framed a poster-sized copy of his 1953 image of Route 66 in Arizona. It’s been hanging on my wall for decades now.

The lonely two-lane highway and the buildings alongside it appear small and ancillary to the sky filled with cumulous clouds that dominate the composition. Feininger succeeds in capturing on film what he must have felt when he experienced Arizona’s expansive and empty landscape.

I understand that Feininger could be somewhat detached, a personality characteristic that I can often relate with. But I think Feininger knew himself well enough to be comfortable with that. In his 1965 book The Complete Photographer, one of my very favorite photography books, Feininger made an honest assessment of himself when he wrote:

Whatever my shortcomings, I have learned to accept them because I have found through experience that it is impossible to change basic traits. Instead, I try to make the best of what I am, to express myself through my pictures as precisely as possible, and to use my camera to give people new insight into some of the endlessly varying aspects of our world.[16]

Rather than try to be someone that I am not or mimic the kind of photography that I might admire but that my own personality type will never easily lend itself to, I have grown more and more comfortable with my own character traits and use them to their fullest potential in the way that Feininger encouraged his readers to do.

More information:

Notes

1 Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002), 239-242.

2 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 575-587; Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 254, 259.

3 “Sadie Pfeifer, a Cotton Mill Spinner, Lancaster, South Carolina,” Art Institute of Chicago, n.d., https://www.artic.edu/artworks/23336/sadie-pfeifer-a-cotton-mill-spinner-lancaster-south-carolina, accessed May 2, 2025.

4 Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 559, 563; Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002), 241; William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 627.

5 “Erich Salomon,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Salomon, accessed May 1, 2025.

6 Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002), 280-282.

7 Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002), 282.

8 Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 164.

9 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 594-595.

10 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 597-598.

11 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 588.

12 Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 149-151.

13 William Johnson et. al., Photography from 1839 to Today (Koln: Taschen, 2000), 612.

14 Museum Ludwig Cologne, 20th Century Photography (Koln: Taschen, 2012), 170.

15 The Great Life Photographers, ed. Robert Sullivan (New York: Bulfinch Press, 2004), 178.

16 Andreas Feininger, The Complete Photographer (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1965), 326.