Blog

Tags: Lunar Astronomy, Astronomy, Astrophotography, Photography, Film Photography, Local Events, Camera Gear, Travel, Book Reports, Adapted Lenses, Everyday Minutiae, Classic Movies, Solar Astronomy, Out and About, Single Frame, Baseball, Classic Cars, Nature, H-alpha Solar Astronomy, Database Development, Advertising, Fashion, Fruits of the Internet, Old TV, Sunsets

“No Kings” Protest on Film

October 28, 2025 | Another opportunity to do some people photography and personal photojournalism on film.

I Did Not Buy a Leica, Part Two

October 2, 2025 | A recent experience with a Voigtlander Vito II folding camera confirmed that owning a Leica rangefinder is not for me.

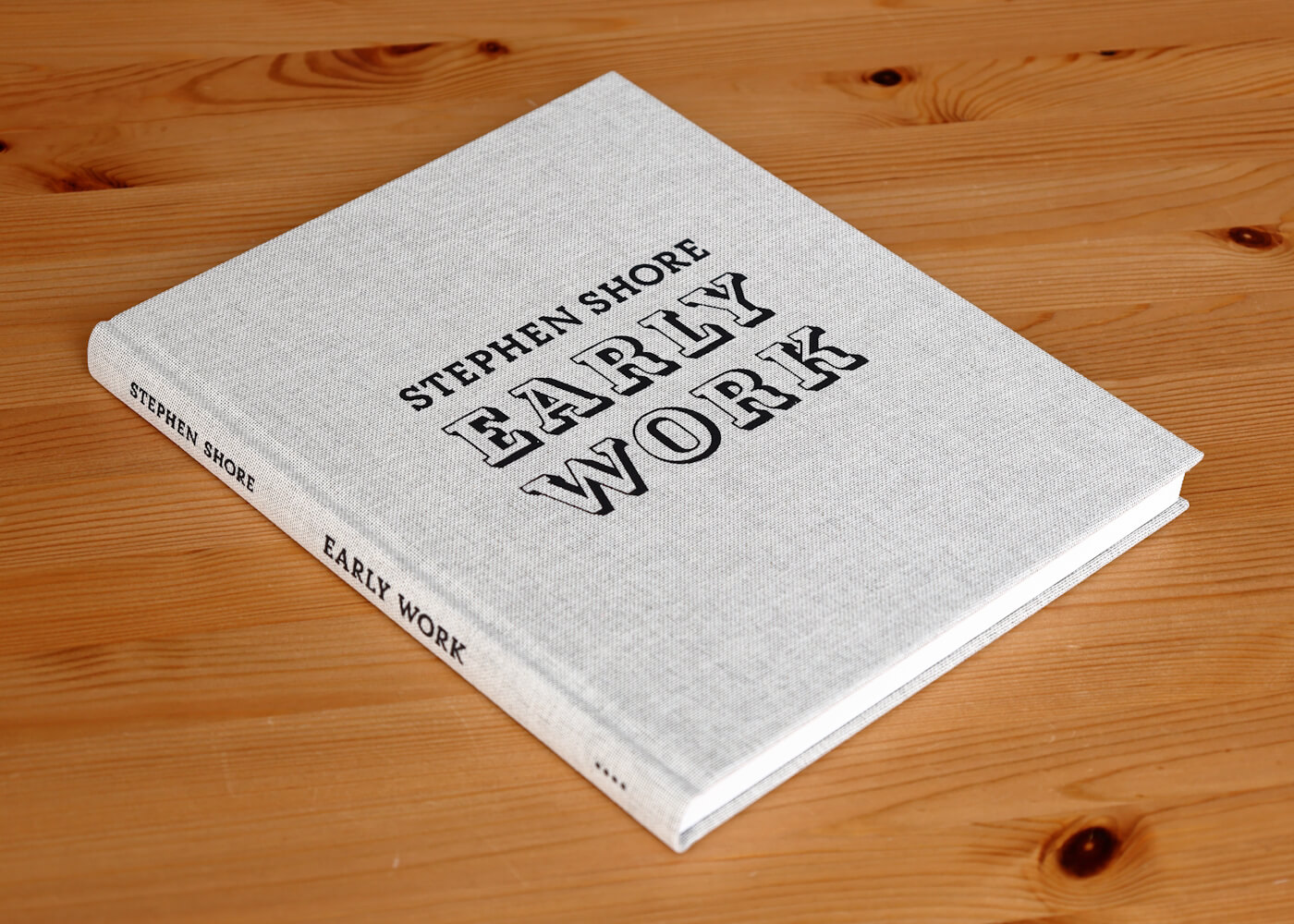

Favorite Photographers

September 16, 2025 | I have greatly expanded my discussion of individuals whose work I admire.

Fire Dancers

August 7, 2025 | Serendipity brought me an opportunity to do some rather unconventional people photography.