Introduction

It was the culmination of years of planning and even more years of tinkering, collaborating, and dreaming. After maintaining a lifelong interest in astronomy, Lawrence Braymer was on the eve of bringing a revolutionary telescope to production.

Together with his wife Marguerite, Lawrence made preparations to begin the marketing for his new product. The Korean War and the subsequent restrictions on materials had temporarily frozen his progress.[1] After hostilities ended in July 1953, those restrictions finally lifted, and Lawrence eagerly began operations. By the spring of 1954, he had an attractive twenty-four-page promotional booklet for the Questar telescope on the way, a booklet that demonstrated his flair for writing, his innovative spirit, and his deep interest in the history of astronomy and the place of his creation in it.

Paging through his copy of Sky and Telescope for March 1954, Lawrence saw the current state of astronomy as both a hobby and a science. Humanity’s first baby steps beyond the gravitational confines of Earth were still over three years away, and our vision of what lay beyond our home depended on the imagination of illustrators like himself. On the cover, Sky and Telescope included an artist’s drawing of what the zodiacal light might look like from space.

Turning into the magazine, Lawrence encountered an announcement written by the famous astronomer Harlow Shapley informing readers that Harvard Observatory had appointed Donald Menzel—a future Questar owner—as director. Next was a piece on the zodiacal light and the solar corona. Its authors speculated about what “pioneers on the earth’s first artificial satellite” would be able to see. Otto Struve, the renowned cataloger of double stars, contributed a discussion entitled “Quantitative Spectral Classifications” in which he presented an in-depth discussion of the topic based on stellar absorption lines and bands.[2] And in subsequent pages, Sky and Telescope presented other content in the same tradition that the magazine follows even today: it reported on other news from professional and amateur astronomers, offered observing tips, and included its monthly map of the night sky.

But perhaps most eye-catching both then and now, numerous advertisements by a wide range of companies beckoned readers. On the inside front cover, a full-page spot by J.W. Fecker highlighted a massive twenty-four-inch Cassegrain-Newtonian reflector that the company had designed and manufactured for Vanderbilt University.[3] Few if any amateurs would have been able to afford let alone maintain such an instrument. More attainable products appearing in other advertisements included the 3.5-inch Skyscope reflector, a bevy of surplus optics sold by Edmund Scientific, Unitron’s signature refractors, and a series of orthoscopic eyepieces offered by Chester Brandon.[4]

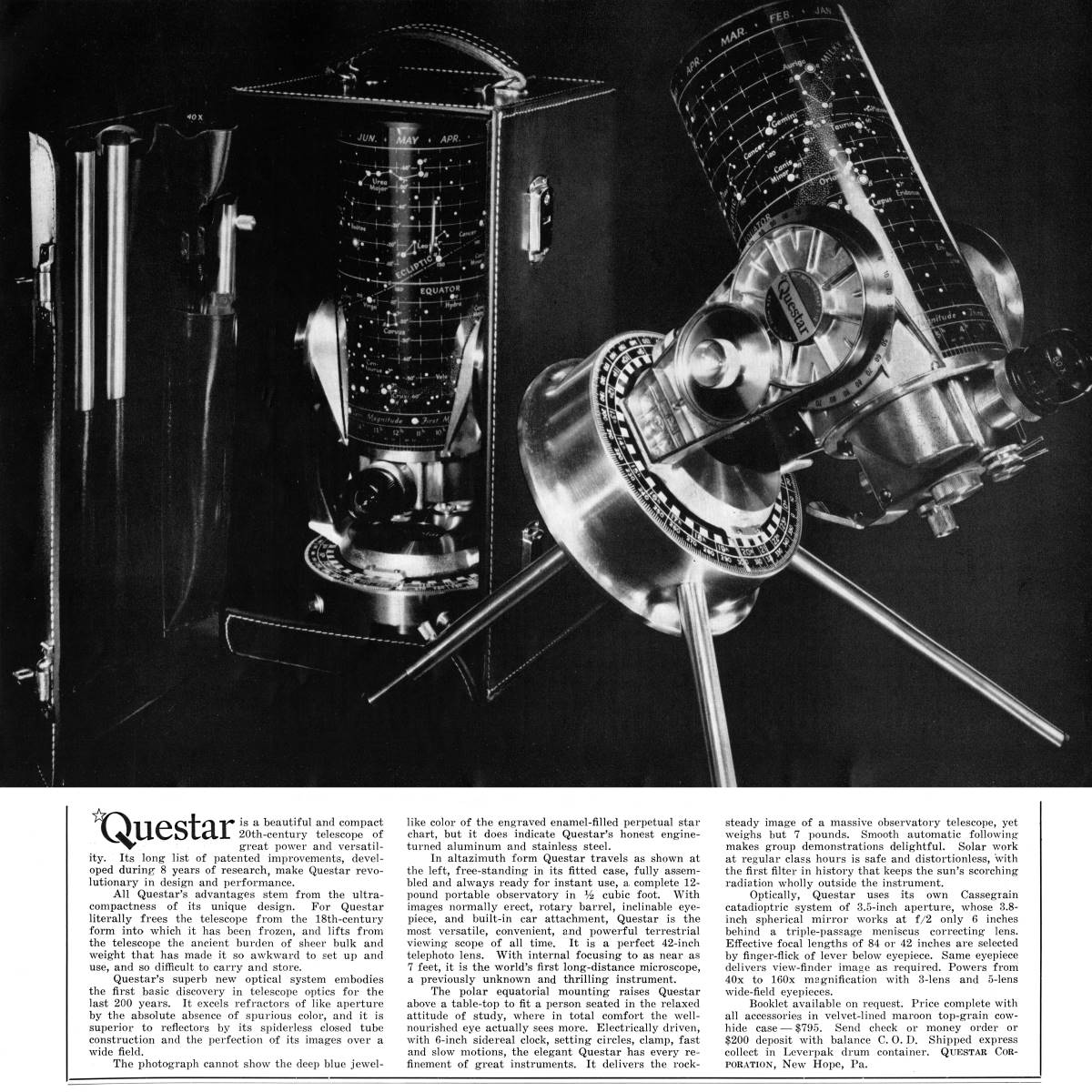

It was this marketing parade that Lawrence Braymer sought to join. Meeting Sky and Telescope’s deadline for the June 1954 issue, he submitted an advertisement containing full-page photograph of a unique 89mm telescope. Its accompanying copy lauded this new catadioptric instrument, the first commercial Maksutov-Cassegrain to reach the market, as a breakthrough in twentieth-century optical design. “All Questar’s advantages stem from the ultra compactness of its unique design,” Braymer wrote in that first advertisement. “For Questar literally frees the telescope from the eighteenth-century form into which it has been frozen, and lifts from the telescope the ancient burden of sheer bulk and weight that has made it so awkward to set up and use, and so difficult to carry and store.”[5] Considering that the vast majority of telescopes that appeared in the magazine were either long-focus refractors or reflectors on bulky equatorial mounts—and considering that first word of the design on which this new telescope was based had been published only ten years before—his claim was not unwarranted.

That first advertisement for the Questar telescope continued to describe how it emerged from eight years of research. Had its focal length been housed in a more conventional telescope tube, it would have been over four feet long. But thanks to its novel design, the Questar folded that light path into a tube not more than nine inches long. Including features like a set of tabletop tripod legs, an electrically-driven fork mount, a rear axial port for attaching a camera body, a built-in diagonal and amplifying Barlow lens, and a solar filter, the whole package—“a complete 12-pound portable observatory,” as Braymer dubbed it—fit into a saddle leather case a half-cubic foot in volume. And it was beautiful to look at.[6]

The earliest Questars had their imperfections. Their spherically-figured optics focused light at different points, and they delivered somewhat of a blurred image as a result. The diagonals were made from Amici prisms, which were less efficient for transmitting light than other materials. A narrow axial port and other optical limitations caused vignetting when the telescope was used for photographic applications. And perhaps most notably, Questar placed the secondary mirror spot on the outside surface of the corrector lens. A design decision compelled by patent constraints, that placement further reduced light transmission and created a significant area of glare around bright objects from the reflection of light off the inside surface of the corrector lens.

Over time, the company remedied these imperfections. Questar switched to aspheric optics in late 1957, changed to a star diagonal by 1960, implemented the so-called wide-field construction in 1964, and relocated the secondary spot to the inside surface of the corrector lens by the late 1970s. Questar introduced other refinements in a continual process of improvement that the company never stopped practicing over the years. But in all that time, the major elements of its design never changed.

After its first appearance in Sky and Telescope in June 1954, Questar grew as a company. Not only did it keep its chain of advertisements in Sky and Telescope unbroken for the next forty years. It also expanded its reach. Running advertisements mostly conspicuously in Natural History and Scientific American magazines, the company tailored its message to new and larger audiences of naturalists, scientifically-minded generalists, photographers, educators, and research institutions.

To be sure, no amount of advertising can mask inferiority for long, and Questar’s success would have been short lived had its product failed to live up to its claims. But the opposite proved to be true, and the company successfully used its conspicuous and elegant marketing to cultivate and cement its reputation over the course of decades. While Questar telescopes deserved their reputation for high standards in optical and mechanical quality, it was Lawrence and Marguerite Braymer’s virtuosity in advertising that distinguished their product and elevated it above all others.

Ask any amateur astronomer who was engaged in the hobby at any point in the twentieth century about what they know of Questar telescopes, and that individual will most likely describe memories about seeing the company’s magazine advertisements. For many, it was the advertisements that stoked at least a sliver of wonder about what it was like to have a Questar. For some, it was the advertisements that fueled an aspiration to own one someday.

But the advertising that Questar so masterfully ran for decades is only part of the tale. From the moment it came out of its case to the moment it returned, a Questar telescope gave its user a unique experience unlike anything that more typical astronomy gear offered. Its aesthetic beauty, clever design, convenient size, and fine craftsmanship was obvious to anyone looking at it. It was not the best telescope for every application—no telescope is. But for those applications that it was best suited to, the performance of the Questar telescope outshined most others.

Lawrence Braymer had both the vision to conceive of such an instrument and the energy to make it a reality. Just as Henry Ford put a permanent stamp on the automobile industry, as Questar wrote in its 1989 booklet, so too did “Lawrence Braymer put a permanent stamp on the concept of the telescope by making it small, portable and yet uniquely precise in performance.”[7] And as classic telescope collector Stewart Squires wrote, Braymer had “the drive and ambition and a wonderful dream to create something using imagination and innovation.” He was not an optician by training or profession but was rather an individual with a background in advertising who was also a tinkerer, an ideas man, and a self-taught engineer. Collaborating with other individuals and companies to design and produce the Questar telescope, Braymer “inspired others to join in the endeavor.”[8]

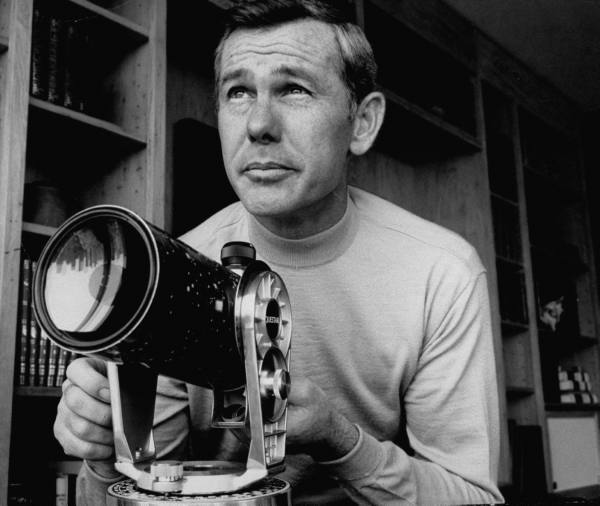

Others indeed played a role in the history of Questar. With every new product or design refinement, an individual with a unique background and personality drove its development. Braymer worked with Norbert Schell, an optics designer from western Pennsylvania who was responsible for much of the initial development of the Questar Telescope. John Schneck drove much of Questar’s early production effort and worked for the company well into the 1970s. The famous entertainer Johnny Carson was a passionate amateur astronomer who pushed for the development of an accessory that made the Questar telescope safer to use for solar observing. Robert Little was another talented amateur whose tinkering led to a number of accessories that made the Questar better for astrophotography. Hubert Entrop, who worked for Boeing as an aeronautical engineer and who raced hydroplanes as a hobby, brought more innovations for long-exposure imaging to the Questar. Others added their contributions, too.

On the receiving end of this stream of innovation was a distinguished group of persons who owned and used Questar telescopes: celebrities, obscure scientists, impossibly wealthy individuals, and those who could barely scratch together enough savings to buy one. Ownership of a Questar telescope said a lot about their interests, their personalities, the aspects of their character that made them extraordinary, and the way they were drawn to a distinguished piece of fine craftsmanship.

Questar fully realized this, of course. In an advertisement that it ran in the August 1965 issue of Sky and Telescope, the company wrote that “the versatility of Leonardo da Vinci was so prodigious that we look back on him as one of the greatest geniuses of all time. He worked in every field. Whatever he touched, he improved, and the wide range of his activities still inspires us with awe.” Linking da Vinci to its customers—and surely flattering them in the process—Questar continued to write that “perhaps one measure of a man is the breadth of his intellectual curiosity, the number of his interests. Unless you who read these lines are a professional astronomer, your interest in our little telescope proves something about you, too. Questar was made for people like yourself, who have inquiring minds.”[9]

Along with these individual owners, those institutions and organizations that were engaged in special applications needing precision optics called upon Questar to satisfy their requirements. A Questar telescope was along for the ride during the Gemini and Apollo missions. Countless laboratories used Questar instruments as part of their research and development activities. And Questar telescopes participated in surveillance missions many of which will remain secret.

In light of all this, the Questar telescope becomes almost a secondary, even incidental part of a larger story. The character of the persons who developed it, the owners and organizations who used it, and the variety of ways it served a purpose all lie at the heart of a compelling tale.

The history of Questar and its signature telescope runs in parallel with the overall history of the astronomy hobby over the course of the entire twentieth century. Consider several milestones in that history and the appearance of Questar and its creator along the way: the emergence of the amateur telescope maker movement in the 1930s and Lawrence Braymer’s participation in it; the emergence of Dmitri Maksutov’s design in the 1940s and the Questar as its first production instance not long after; the rise of astrophotography and the accommodation of that function as one key feature of Questar’s design, and so forth. Throughout amateur astronomy’s history in the second half of the twentieth century, Questar emerged time and again.

While Questar’s prominence grew during the 1950s and 1960s, other telescope manufacturers introduced products that mimicked it. Companies like Tinsley Laboratories, Thermoelectric Devices, and Cell Optical Industries all produced telescopes that were based on Maksutov’s design. Some even included tabletop mounts that could be equatorially aligned. Their similarity to Questar could hardly have been missed. Before long, the company no longer had the market for Maksutov-Cassegrain telescopes to itself.

Questar faced increasing competition in other forms. With the emergence of new telescope designs and other developments, it continued to assert its relevance as the maker of products whose quality was unsurpassed. The company reacted to the increasingly prevalent Schmidt-Cassegrain by questioning the optical quality of instruments whose design was inherently difficult to mass produce. In reaction to the Dobsonian revolution and the dramatic increase in aperture it brought to amateur astronomers at an equally dramatic low cost, Questar asked whether a cumbersome “light bucket” could deliver a sharp image under poor seeing conditions. The emergence of apochromatic refractors and computerized mounts also drew the attention of Questar’s marketing copywriters. And with Meade’s introduction of the ETX 90, the company had yet another imitator to contend with. By the end of the century, consumers enjoyed more purchasing options than ever before, and Questar found itself in a very different position than the one it had enjoyed five decades earlier.

Few would question the benefits that these developments brought to amateur astronomers. Telescopes manufactured overseas demonstrated astoundingly high quality at a cost that was a fraction of what domestically-made instruments were obtainable for even a handful of years prior. And with the growing prominence of first-rate telescope makers like Takahashi, Astro-Physics, and Tele Vue, competition on the high end of the market became just as intense as it had become on the low end.

But no other manufacturer could muster both the enduring loyalty that Questar enthusiasts had for their telescopes and the lore that surrounded them. By the late 1990s, when the internet had gained widespread acceptance, a coalescing online community of Questar owners was one indication that the company that built their telescopes had not faded. And with the introduction of the 50th Anniversary Questar, both that community of enthusiasts and the company itself celebrated the continuation of Lawrence Braymer’s original vision into the twenty-first century.

What follows is not merely the story of a telescope. It is the story of how one notable example of groundbreaking innovation in astronomical instrumentation unfolded. It is the story of design and production at its highest level. It is the story of the creation of artwork that serves a functional purpose. It is the story of a product and a company that demonstrated persistent staying power amid vast change. And it is the story of a telescope interwoven into American culture and the lives of those who participated it. In a word, it is the story of a legend.

Notes

1 Charles Shaw, “Larry Braymer: ‘In Quest of the Stars,’” New Hope Gazette, March 14, 1985, 3, 32, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed October 15, 2019.

2 Harlow Shapley, “Harvard Observatory Director Appointed,” Sky and Telescope, March 1954, 143, 149; Rodger Gordon to the author, September 23, 2020; F. E. Roach and G. Van Biesbroeck, “The Zodiacal Light and the Solar Corona,” Sky and Telescope, March 1954, 144-146; Otto Struve, “Quantitative Spectral Classifications,” Sky and Telescope, March 1954, 147-149.

3 J.W. Fecker, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1954, inside front cover.

4 Skyscope Company, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1954, 163; Edmund Scientific, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1954, 165; United Scientific Company, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1954, 167; Chester Brandon, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1954, 173; United Scientific Company, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1954, outside back cover.

5 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, June 1954, 272-273.

6 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, June 1954, 272-273.

7 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1989, 3-4.

8 Stewart Squires, online forum posting, Questar Users Group, January 8, 2004, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/conversations/messages/7320, accessed October 13, 2019; Stewart Squires, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, June 22, 2018, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/622519-time-machine/?p=8657961, accessed November 3, 2019.

9 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1965, inside front cover.