§ 2.4. Adoption and Influence

On This Page

“The list of Questar owners is a most impressive one,” Lawrence Braymer crowed in May 1958. He had good reason to: his company had become a genuine success. “Men and women in all walks of life are Questar owners, and many of them are distinguished persons.”[1]

Along with hundreds of less distinguished persons, numerous organizations had also taken notice of the small Maksutov-Cassegrain that emerged onto the market in 1954. Schools, colleges, and universities bought Questar telescopes for use in educating their students. Professional astronomers also acquired them for wide range of purposes, as did researchers who worked in scientific and industrial laboratories.

The Questar telescope received positive coverage in both the press and in exhibits that featured them as examples of good design. Recognizing the success of their new competitor, other telescope manufacturers saw opportunities to seize a piece of the action. Before long, they began making Maksutov-Cassegrain telescopes of their own, and some of them bore striking resemblance to the first one that had appeared on the market. Amateur telescope makers also tried their hand—often with remarkable success—at figuring the complex optics that Maksutov’s design called for.

Celebrity Questar Owners

While many other advertisers may have eagerly leapt at the opportunity to associate their product with a famous owner, Questar avoided using direct celebrity endorsements as a promotional device. Only on relatively rare occasions did the company mention that a celebrity was an owner of one of its telescopes. When they did so in an advertisement, Questar made only passing mention of the fact. Never in its marketing history did the company include a picture of a celebrity posing with one of its products. Perhaps Questar’s reluctance to highlight celebrity ownership in its advertising was part of its overall policy to protect the privacy of its clients. Or perhaps the company did so simply as a matter of good taste.

Over time, ownership of a Questar telescope became a symbol of elegance. It was only natural that celebrated members of the public who desired such things joined many other Questar owners who had similar interests. A general sense of curiosity about science, a particular fascination with astronomy and space exploration, an appreciation for precision gadgets, or a desire for the prestige of owning a hallmark instrument: for all of these reasons and more, they naturally gravitated to the Questar.

Wernher von Braun

The Questar owner with perhaps the strongest link to the Space Age was Wernher von Braun, the leading rocket engineer and advocate for the exploration of space during the middle part of the twentieth century. Born in 1912, he had maintained an interest in space flight since his teenage years, an interest that drove him to earn his doctorate in physics by the age of twenty-two. Leading the team that developed the V-2 ballistic missile for Nazi Germany during World War II, he realized at the end of 1944 that the war was hopeless, and he prepared for Germany’s inevitable defeat. Surrendering to the Americans in Bavaria, von Braun and many of his colleagues spent the next fifteen years developing ballistic missile technology for the United States.[2]

Von Braun did much of his work during the 1950s at Redstone Arsenal (RSA) just outside of Huntsville, Alabama. Emerging as the U.S. Army’s center for ordnance rocket research and development, RSA housed various military agencies that von Braun led. He and his fellow engineers continued their work developing weapons missiles amid heightening tensions during the Cold War. But using rockets for space exploration never left his mind.[3]

With the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik in October 1957, von Braun made a forceful case for what his “space team” could do. In a handful of months, he and his colleagues developed the rocket that put Explorer I into orbit on January 31, 1958.[4]

Dwight Eisenhower eventually transferred the U.S. Army’s space flight development efforts under the newly-organized National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and he moved von Braun and his team to the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville in late 1959.[5] Before he did so, however, von Braun managed get Redstone Arsenal to requisition a trio of Questar telescopes. According to correspondence between the Kennedy Space Center Amateur Astronomers and Questar Corporation in July 2003, the telescope that von Braun personally used was built on May 18, 1959. The instrument is still in the possession of NASA at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.[6]

Apart from his rocket development work, von Braun engaged the public as a leading proponent of space exploration. In the mid-1950s, he partnered with Walt Disney to produce three television films the first of which was entitled Man in Space. And in 1959—perhaps drawing his inspiration from his new Questar telescope—von Braun published a short booklet in which he speculated about a potential lunar landing. In the 1960s, he found himself well positioned to realize that vision. As director of the Marshall Space Flight Center, he helped developed the Saturn V rocket that propelled the Apollo missions to the Moon in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[7]

Betsy Drake and Cary Grant

Far better known to the public were Betsy Drake and Cary Grant. “Perhaps we have been too strict about mentioning famous people who own Questars,” Lawrence Braymer wrote in 1961. “So we might mention that the Cary Grants own two Questars. Mr. Grant explained that they have three houses—his wife has one, he has one, and they have one, so that is why he bought the second Questar. We hope this is clear—three houses, two Questars.”[8]

Betsy Drake, Cary Grant’s third wife, was likely the reason why Braymer could count both film actors as two of his clients. On top of her skills as a writer and actress, she had “the blond, well-bred looks and brains of a Bryn Mawr honor student,” wrote Look magazine writer Laura Bergquist in 1959. Although she sometimes accompanied her husband as he went “hobnobbing with tycoons,” Drake was unimpressed with the trappings of fame. More often, “she stayed home and doggedly worked at her interests, among them photography, astronomy, and writing.”[9] But Cary was not totally unaffected by his wife’s influence. He credited Betsy for encouraging him to look beyond his career and expand his interests into other areas. Unfortunately, the couple’s separation in 1958 at least partly explained their ownership of multiple houses—and multiple Questars.[10]

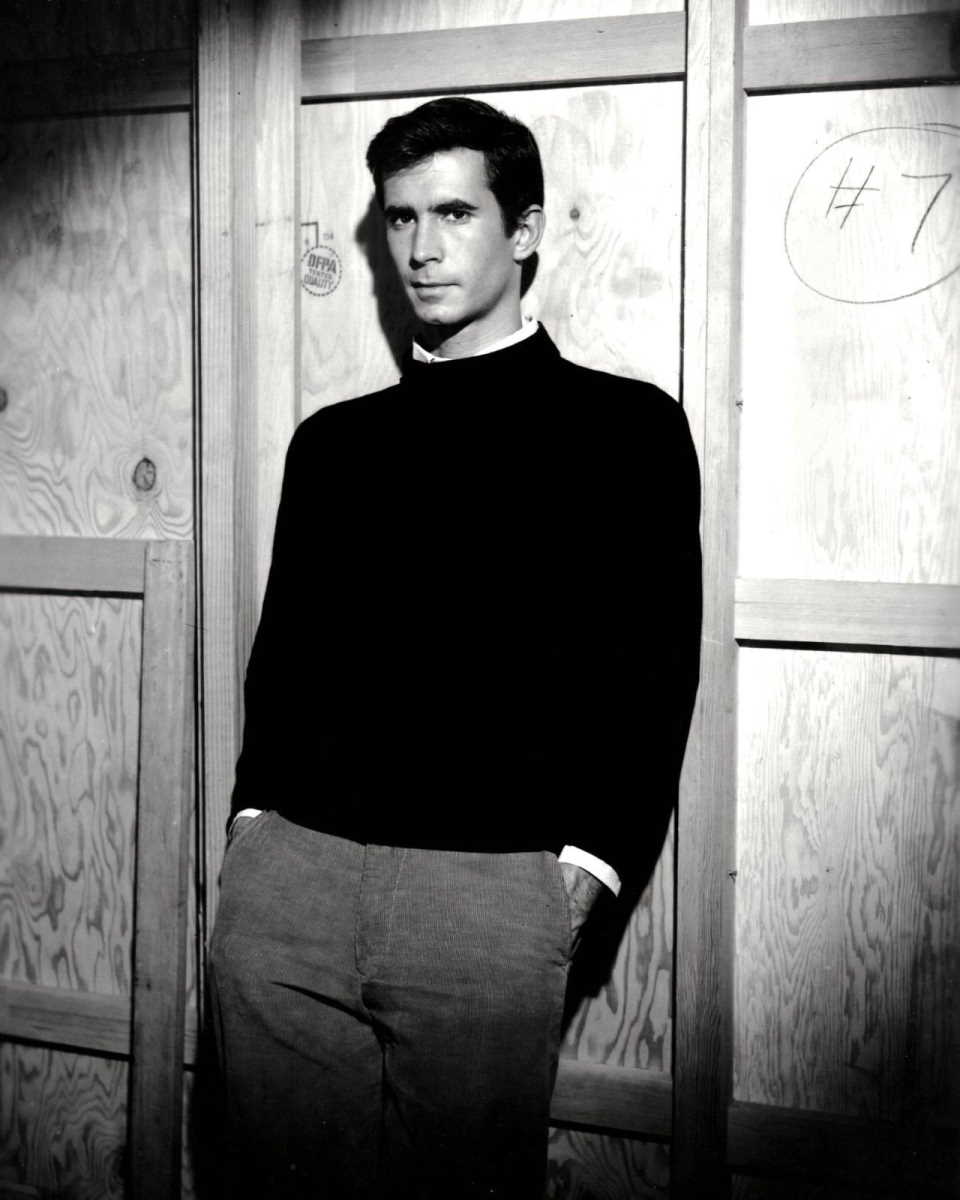

Anthony Perkins

Another film and stage actor who held a genuine and long-standing interest in astronomy was Anthony Perkins, who was 28 years old when he acquired his Questar telescope in 1960. Lawrence Braymer could not resist adding his testimonial to his advertisement that appeared in the August 1960 issue of Sky and Telescope. “While playing the lead in the Broadway musical ‘Greenwillow,’” Braymer wrote, “the distinguished American actor Mr. Anthony Perkins phoned us from New York. We learned that he had used telescopes since boyhood, has a 4-inch refractor, and has practically memorized our booklet. He asked some questions and in June took delivery of a quartz-mirrored Questar. When asked how he liked it, he said, ‘Your booklet does not do it justice.’ We asked if we could quote him in his space. ‘Indeed yes,’ he replied, ‘but change that to read ‘no catalogue could do it justice.’”[11]

Perkins added his Questar to his telescope collection the same month that Alfred Hitchcock’s film Psycho, the movie that gained him international fame, was first screened at the DeMille Theatre in New York.[12]

Another extended link that Perkins enjoyed with astronomy was one that ran through his wife, the American actress, model, and photographer Berry Berenson. She was the maternal great-grandniece of Giovanni Schiaparelli, the Italian astronomer who “discovered” the canali on Mars.[13]

King Mohammed V of Morocco

By the late 1950s, the Questar telescope had gained notoriety among not only prominent scientists and entertainment celebrities but also heads of state. Seeing it as a suitable token of friendship, Dwight Eisenhower gave a Questar telescope to King Mohammed V of Morocco during a state visit to the United States in late November and early December 1957. Two years prior to the visit, Mohammed had returned from exile before negotiating with France and Spain for his country’s independence.[14]

Quick to draw attention to this honor, Lawrence Braymer included a rather conspicuous indication of Eisenhower’s presentation in his advertisement that appeared in the February 1958 issue of Sky and Telescope.[15]

Whether the prominence that the company gained was a direct outcome of Eisenhower’s gift or was simply a matter of coincidence as the company’s fortunes increased with time,[16] it was clear that Questar had earned a remarkable level of acceptance and had established itself in the minds of many individuals across many walks of life.

Organizational Clients

By the early 1960s, the company could boast about the long and varied list of organizations that had purchased a Questar. In an advertisement that ran in the April 1962 issues of both Sky and Telescope and Natural History magazines, it identified fifty research laboratories and industrial users, fifty-five institutions of higher education, twenty-three government agencies, and thirteen observatories and museums.[17] Two months later, Questar added nineteen secondary schools to the list.[18] The number of organizations that the company enjoyed as clients only grew in subsequent years.

Schools and Public Outreach

Lawrence Braymer put a high priority on getting Questar telescopes into the hands of educators. He argued that many of its characteristics—its small size, its ability to function as a solar telescope, its motorized tracking, and so forth—made it ideal for educational settings and public outreach events. Because of its compact design and minimal storage requirements, Braymer wrote in his 1954 Questar booklet, “schools no longer need think of astronomy in terms of costly rotary domes to house traditional instruments.” Instead, “even the smallest school can now afford to keep an observatory on its microscope shelf. We hope to interest schools in the idea of acquiring Questar as a community project, so that everyone, young and old, may have the unforgettable experience of direct high power observation of celestial objects, for which there is no substitute.”[19]

In particular, the company noted that the Hayden Planetarium had taken delivery of a Questar for use in nighttime astronomy classes. Public schools in San Diego and Yuba City had bought them along with Southern Connecticut State College in New Haven.[20] Countless other schools, colleges, and universities had done the same.

Schools and institutions were not the only ones to use Questar telescopes to introduce members of the public to the wonders of the night sky. Decades later in their Backyard Astronomer ’s Guide, Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer remembered one fellow astronomy enthusiast who regularly shared his views of the heavens to passersby:

The late James Kemp... spent mild summer evenings with his Questar telescope in a city park near his apartment in downtown Toronto. We often wondered whether some night he would emerge from the park without his telescope, its having been scooped up by someone nasty. It never happened. Instead, a small crowd inevitably joined him, each person waiting patiently for a look.

An articulate man with a gift for exposition, Kemp would entrance the crowd with constellation mythology, explanations of black holes and spacecraft-exploration results. As he pointed to the few stars that could be seen through the city glow, heads would swing in synchrony, everyone listening intently. Those nights were impromptu stargazing parties that Kemp enjoyed as much as did the guests who never knew his name.[21]

Professional Astronomers and Observatories

Marguerite Braymer remembered her company’s early success in getting professionals to adopt the Questar telescope for use in their work. Within four years after the company’s marketing launch in 1954, “every major observatory was using Questar for locating, for field trips,” she recalled decades later.[22] One could also find Questar telescopes in use by professional astronomers in rather unusual settings.

Alfred Mikesell, Malcolm Ross, and Their Balloon Flight into the Stratosphere

In 1958, astronomer Alfred Mikesell and high-altitude balloonist Malcolm Ross ascended to the stratosphere with a custom-built Questar telescope.

Born in 1914, Alfred Mikesell had cultivated a keen interest in astronomy since his boyhood. Having devoured all the books he could get on the topic from the public library in Fresno, California, he went on to pursue his studies at Fresno State College, where his father was a professor, and the University of California at Berkeley. Eager for real-world experience—and fully aware of the scarcity of professional astronomy jobs during the Great Depression—Mikesell was one of three individuals who successfully took a civil service exam for work at the U.S. Naval Observatory in 1936.[23]

Not unlike Lawrence Braymer, Mikesell was a “mechanically minded astronomer,” as historian Steven Dick wrote.[24] He began his career by conducting research in atmospheric scintillation and its effect on photometry, and he sought ways to eliminate those effects. From there, his interest grew to encompass everything related to scintillation.[25] One application of Mikesell’s work involved attempts to use scintillation as a means to detect atomic bomb explosions anywhere on Earth by measuring optical atmospheric disturbances. Around 1954, he conducted experiments in California on behalf of the Office of Naval Research while atomic tests were underway in Nevada.[26]

In 1955, he consolidated what he had learned in a paper entitled “The Scintillation of Starlight,” which was published in the Publications of the United States Naval Observatory.[27] What he and his colleagues discovered as a result of their research “remains what is known on the subject,” he later recalled.[28]

But a key question remained unanswered: where in the atmosphere is scintillation introduced? At the U.S. Naval Observatory, Mikesell and his colleagues had tried all kinds of ways to gather data in pursuit of a solution. They sent artificial stars up in balloons, helicopters, and kites in an attempt to gather data. But Mikesell knew that the best way to answer the problem was to ascend above the tropopause, a violent layer in the atmosphere where Earth’s weather occurs. Above that, one enters the very stable and clear stratosphere. Mikesell wanted to ascend above the tropopause because he and his colleagues strongly suspected that scintillation was introduced at and below that level.[29]

Developing theories about where scintillation occurred in the atmosphere was one matter, but actually making observations at the necessary altitude was quite another. While Mikesell and two of his colleagues were trying various approaches, Malcolm Ross appeared one day from the Office of Naval Research. Looking for scientific projects as part of his activities in free ballooning to high altitudes, Ross offered to help Mikesell with his research.[30]

Equipped with a wide breadth of experience that included a graduate-level education in physics and meteorology at the University of Chicago, service as an officer in the U.S. Navy, and professional work in advertising, Malcolm Ross had “a burning zeal for balloon flying,” as Mikesell later recalled. After serving in the Korean War, Ross transferred to the Office of Naval Research in 1953. The next year, he initiated Project Strat-Lab and conducted research using high-altitude plastic balloons in the upper atmosphere.[31]

Since using a balloon to ascend high in the atmosphere was by far the best way to find where scintillation is introduced in the atmosphere,[32] Ross and his Project Strat-Lab were a perfect fit for Mikesell’s research. But Ross would not go up alone. Instead, he employed all of his skills as a cunning advertising man to persuade Mikesell to accompany him. Describing a potential balloon flight as “dull routine” and characterizing it as if “there was nothing to it,” Mikesell later remembered, “I said, ‘Oh, sure.’ As simple as that. Later on, I discovered there was nothing routine about it and it had never been done before.” In truth, Ross had flown to 40,000 feet only once, and he had stayed there only for a brief length of time.[33]

Soon, preparations for the flight were underway. With General Mills working as the U.S. Navy’s general contractor, an appropriate balloon was designed, heavy cold-weather clothing was selected, and a gondola containing all the necessary gear for the flight was built.[34]

A key part of the mission’s instrumentation was a Questar telescope. Mikesell had already spoken with an individual who had been site testing for the Kitt Peak National Observatory and who recommended a catadioptric telescope for his flight. In need of an instrument that he could obtain quickly, Mikesell remembered seeing the “fanciful ads” that Questar published about its telescope in various magazines. But he knew nothing else about it.[35]

He realized that a quick fact-finding trip was in order. As Mikesell later recalled:

I went up to New Hope, Pennsylvania, and met with [Lawrence] Braymer, the designer and entrepreneur who put this thing on the market, and had a lot of time chatting with him. Turns out he spent time at the Naval Observatory in his past. And he made up a Questar special. The ordinary catalog model had a barrel that was blue with the map of the stars on it and a map of the moon or something like that on the shade. We wanted just a plain hard-working one.[36]

Ironically, Braymer also included the full-luxury English leather case with the stripped-down telescope that he had built for operation under harsh conditions.

The night before Mikesell departed home to travel to Minnesota for his balloon flight, his wife Mary confided with him about what life would be like “if something happened.” He did not need to ask what she meant. Mikesell later admitted that it was only after the flight that he learned more not only about the balloon he and Ross flew but also about the culture of ballooning in general. Only then did he gain a true understanding of how dangerous it was. Indeed, his was the last high-altitude balloon flight that the military conducted without any serious injuries or deaths.[37]

The day of the flight arrived on May 6, 1958. In an old, inactive iron ore mine near Brainerd, Minnesota, the ground crew filled the balloon with helium. The depth of the mine shielded the balloon from surface breezes as it was inflated. Fearing that the balloon would scrape against its rocky sides, Ross wanted it “good and light” for a fast ascent out of the ore pit.[38]

After a lengthy delay, Mikesell and Ross finally launched around 8:10 pm, well after sunset. With their balloon not even half-full of helium, they ascended to their target altitude in around 35 minutes, four times faster than they had expected. Their climb was so fast that Mikesell observed the Sun appear to rise above the horizon after it had set at ground level. After that, things began to go wrong. Mikesell began to develop abdominal bends. His emergency parachute hindered his movement, and he found it difficult to bend over and do what he needed to do. More problematic for his ability to make observations, the ground crew had effectively created a torsion pendulum: by situating much of its heavy load on its outer edges, they caused the gondola to spin uncontrollably as the balloon gained altitude.[39] Unable to aim it, Mikesell realized that the telescope that he had so carefully selected and that Questar had customized for him was now useless. He never did make observations with the photoelectric photometer that he had attached to the instrument.[40]

After arriving above the tropopause at an attitude of around 40,000 feet, Mikesell and Ross stayed there for around two or three hours. They saw the Sun set again. After the sky darkened—and with his photometer-equipped Questar sitting idly as the gondola continued to spin, Mikesell opted to make simple visual observations instead. And these, he said, “were spectacular. There was no star twinkling until you were looking down almost below the true horizon, the apparent horizon several degrees below us and at the true horizon or just below is where the stars would twinkle from that upper altitude.” In spite of the fact that they had to look through wind shear, stars still did not twinkle above the tropopause.[41]

Remembering past incidents when daytime balloonists fell asleep at high altitude and were frozen to death, Ross became anxious and wanted to begin their descent.[42] Originally, the flight plan called for a series of experiments that required the balloon to stop its descent at the tropopause. When they did so, however, a thick layer of frost covered all of the Questar’s optical surfaces. “The tropopause is an enormous moisture trap,” Mikesell later explained. When the “super-cooled rig” came down through the relatively warm tropopause, frost developed on everything. Mikesell tried to scrape it off, but it was hopeless. Realizing that their planned experiments were impossible and knowing that they had been physically pushing themselves, they gave up and continued their descent. Finding an inversion at 14,000 feet, Mikesell and Ross parked themselves there for the remainder of the night rather than attempt a landing before daylight broke.[43]

Still wide awake, Mikesell took advantage of the opportunity to use his Questar, now cleared of frost, to make some visual observations. At their lower altitude, “the moon, Jupiter and Saturn appeared excellently defined through a 3.5 inch, 160 power telescope,” Mikesell later wrote in his report about the flight.[44] At midnight, Jupiter was on its way to setting almost due west about a third of the way between the horizon and zenith, and Saturn was rising above the southeast horizon. At 4 am, a thin crescent Moon appeared a few hours before the Sun rose around 6:00 am.

Finally at 7:26 am, Mikesell and Ross landed in a farm field near Galena, Illinois, eight miles from Dubuque, Iowa. The total duration of the flight was about eleven to fourteen hours. After landing, Mikesell and Ross turned to “rescuing the important things—rescuing the Questar and any other important things.” Both felt relieved that they had completed their mission after five months of preparation without serious harm.[45]

The Naval Observatory’s official reaction to the flight was not positive. Officials there believed the organization should have nothing to do with such dangerous mission, and they would not allow a second flight. “My colleagues, of course, got a kick out of it,” Mikesell recalled.[46]

The press cast a more positive light on the affair. Only seven months after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in October 1957, “the U.S. papers were looking for any kind of a success, and they caught this as something spectacular and ran it every place.”[47]

Lawrence Braymer ran it, too. Using the same wire service photograph of Mikesell, Ross, and their Questar telescope that appeared in the New York Times the day after they landed,[48] the company ran an advertisement in the July 1958 issue of Sky and Telescope that proudly highlighted its role in the flight. “The Stars Do Not Twinkle at 40,000 Feet,” the headline declared. “Two space explorers, a seasoned balloonist and the first astronomer to observe the heavens from the stratosphere, said on Wednesday, May 7th, that the stars do not twinkle when observed from 40,000 feet. Navy Commander Malcolm D. Ross and Naval Observatory astronomer Alfred H. Mikesell smiled through bearded stubble as they reported the success of their experimental balloon flight.” The landing “did not damage the delicate equipment aboard the balloon.” In conclusion, Braymer wrote that “Mr. Mikesell chose a quartz-mirrored Questar telescope for the trip aloft because of its compactness, lightness, versatility, and ability to furnish good definition at high powers.”[49]

Braymer’s advertisement was mute about the fact that the astronomer was unable to use his Questar telescope to make his planned observations. But no one had ever gone above the tropopause even though ballooning had been around for hundreds of years.[50] On top of this feat, Mikesell also achieved the distinction of becoming the first astronomer to make observations from the stratosphere.[51]

He and Ross also stumbled upon a few unexpected discoveries. During the phase of their flight above the tropopause, they released a smoke bomb and observed its trail. They discovered that wind shear and air turbulence exist even above the tropopause.[52]

The flight led to another more significant finding. In spite of their cold-chamber testing in preparation for the balloon flight, Mikesell and Ross’s cold-weather gear ultimately proved ineffective. After they crossed the tropopause, their body heat began radiating through their clothing, and they suddenly felt extremely cold. Unknown to Mikesell and Ross prior to their flight, their clothing acted as a 95% efficient black body, as a report published by Ed Ney showed. The Navy “immediately went over experimenting with evaporative depositing of aluminum onto clothing,” Mikesell recalled. “They found that aluminum reduced it to 5% efficient” black body. “Of course, the people going into space were taking this kind of clothing to defeat solar radiation, because they had to keep cool.” But the discovery also changed the way that anyone who might radiate out heat loss in cold-weather conditions was equipped. This included navy officers on submarine watch in conning towers twenty feet above water, officers who were grateful for clothing that finally kept them warm.[53]

Vladimir Zworykin and L. E. Flory

Just as Wernher von Braun, the man who led the development of the rocket that launched the Apollo missions into space, was a Questar owner, so too were the individuals who helped develop the technology that enabled millions to witness those missions first hand. By the late 1950s, Vladimir K. Zworykin and L. E. Flory had already published their thoughts on the usefulness of television. One paper was entitled “Television as an Educational and Scientific Tool.”[54]

In February 1961, as Lawrence Braymer wrote in his “Questar News” advertisements, they were continuing their research and development work when, on her first day on the job, Questar’s new secretary received Zworykin and Flory at the company’s office in New Hope. They had just arrived from nearby Princeton University to take delivery of their new instrument. Clearly proud that his telescope would play a role in their research, Lawrence Braymer wrote that the pair, who had just finished work on the guidance system for the balloon-borne Stratoscope II telescope project, were “about to tackle the control system for a larger manned telescope in a space vehicle which will operate from orbit. For convenience the system will point the little Questar instead of the huge machine it will eventually control. What a wonderful business this is when it gives us such glimpses of the instrumental frontier!”[55]

Questar at Haleakala and Mauna Kea

Closer to the ground, the physics department at the University of Hawaii used Questar telescopes to evaluate potential observatory sites at both Haleakala on Maui and Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii. This work followed the groundbreaking progress that professional astronomy had made with the Kitt Peak National Observatory and other similar projects in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

It was not Questar’s first point of contact with the University of Hawaii. Earlier, Charles E. K. Mees, a photographic equipment developer who created and directed the Kodak Research Laboratories at Eastman Kodak Company, bought a Questar upon retiring in 1955. Before his death in 1960, he stipulated in his will that his telescope should be given to the university.[56]

It was a small token of Mees’s dedication to the fledgling institution, and the university reciprocated by naming the C. E. K. Mees Solar Observatory after him. Completed in 1963 near the summit of Haleakala, it was a memorial to Mees’s advocacy for Hawaii’s mountaintops as locations for serious research.[57]

In 1964, the university welcomed John T. Jefferies to lead its overall astronomy research program.[58] In an effort to formulate plans for the new equipment at the Mees Observatory, Jefferies consulted with Dick Dunn of the Sacramento Peak Observatory in New Mexico and Joe Rush of the High Altitude Observatory in Boulder, Colorado. Jefferies later remembered that, in addition to joining the observatory’s staff for a few years to oversee the construction on a new coronagraph-spectrograph, “Rush also undertook to evaluate the daytime seeing on Haleakala using a Questar telescope to make visual observations of the sun at various sites on the mountain.” His observations underscored the degree to which Haleakala was well-suited for solar research.[59]

But not long after the completion of the Mees Observatory on Haleakala, an opportunity to build a large telescope for nighttime observing appeared. After months of negotiation among various parties including the State of Hawaii, the University of Hawaii, and NASA, an agreement emerged on July 1, 1965, to spent $3 million for the construction of a seven-foot telescope. The next task was to decide on a location.[60]

Over the next six months, Jefferies and his team focused their attention on two potential sites: Haleakala and Mauna Kea. The latter had far more primitive infrastructure, and it suffered from high winds and heavy snow. “Clearly it would have to offer a distinctly superior observational quality to compensate,” Jeffries wrote. Two key criteria emerged in the decision-making process: infrared transparency and atmospheric seeing. Jefferies’s team evaluated the latter using a double-beam telescope that detected differential motion and a pair of borrowed Questar telescopes whose fine optical quality could enable star tests with diffraction rings around a bright central core.[61]

To lead the team on Mauna Kea, Jefferies selected Jim Harwood, who had called Jefferies early in 1965 after he learned about the project proposal. The evaluation staff endured the dangers of high altitude, harsh cold, and sheer loneliness—conditions that tested their commitment. After six months, Jefferies and his team concluded that Mauna Kea had the advantage in terms of seeing, clear skies, and atmospheric transmission of infrared light. But its high altitude remained a concern. In the final analysis, however, they concluded that it was not an insurmountable obstacle considering that the evaluation staff had proven their ability to function even in the extreme conditions at Mauna Kea. “So, not without some trepidation,” Jefferies wrote, “we recommended that the telescope be built on Mauna Kea.” In March 1966, NASA accepted their findings.[62] Construction began the following year.[63]

Less than three years later, Jefferies and his colleague William M. Sinton published a report entitled “Progress at Mauna Kea Observatory” in the September 1968 issue of Sky and Telescope. After summarizing their site evaluation work and remembering the Questar telescope they used to do it, Jefferies and Sinton said that work on the 88-inch reflector and its observatory building was proceeding apace.[64] In 1970, the instrument finally saw first light.[65]

Other Professional Astronomers and Observatories

Beyond Haleakala and Mauna Kea, other institutions used Questar telescopes to evaluate potential sites for new observatories. Between 1962 and 1964, R.M. Petrie and G.J. Odgers used an eight-inch Cassegrain reflector and a 3.5-inch Questar telescope to conduct an initial survey of conditions at Mount Kobau in British Columbia. But after Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson officially announced the observatory project in 1964, opposition to it emerged and grew. Officials finally cancelled the undertaking in 1968.[66]

In a number of advertisements, Questar was quick to list other professional astronomers and observatories that made use of the company’s instruments. In the April 1960 issue of Sky and Telescope, Lawrence Braymer used one of his “Questar News” installments to tell the story of Bart Bok, an astrophysicist who was the director of the Mount Stromlo Observatory just outside Canberra, Australia. In June 1959, he and his wife arrived in Brisbane, Australia, to deliver an address at the University of Queensland. The receiving party at the airport realized that no one had ever seen Professor Bok and had no idea who to look for. But then someone remembered that he had promised to bring his Questar with him. Its signature English leather case ultimately proved to be effective way for identifying Bok in a crowd.[67]

One could also find a Questar telescope at the Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte in Naples, the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, the Dominion Observatory in Ottawa, and many other institutions.[68]

Special Applications by Researchers and Industry

The company’s instruments served in a variety of special application settings far beyond astronomy. Confident in his product’s usefulness, Lawrence Braymer wrote in his 1954 booklet that “industry will discover many uses for Questar” given its ability to monitor hazardous conditions from a safe distance.[69]

Six years later, his prediction ultimately proved true. In the September 1960 issue of Scientific American, the company noted that, “although most of our sales are to individuals, each week we ship more and more Questars to laboratories and special projects great and small.” Although many of them are unknown, the company did hint that that some Questars “follow missiles, find and photograph re-entering nose cones, and take high speed pictures of tiny particles. Where exploding wires formerly fouled a near lens, Questars now record the event from the far side of the room. They feed all sorts of motion picture cameras and color television devices. The latest operating theatres here and abroad plan to build Questars in for closed circuit viewing of surgery.” In a pitch to the laboratory decision maker, the company suggested that “the staff as well as yourself will find its use after hours a stimulating and rewarding experience.”[70]

In addition to Sperry Gyroscope, du Pont, and Electronics Corporation of America,[71] industrial users of the company’s telescopes included Corning Glass Works, where “a research project has employed a Questar to take various kinds of 16 mm. motion pictures in a study of what occurs at the juncture of molten glass, tiny crucible and air at temperatures around 3000°.”[72]

In the early 1960s, the Atomic Energy Commission acquired a Questar for use at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Again seeing an opportunity for another demonstration of its instrument’s usefulness for novel applications, the company ran an advertisement in the July 1961 issue of Scientific American. It highlighted the way in which a Questar telescope “permitted metallurgists to work, without protective clothing, in comfort and safety while examining the interior of a radioactive core vessel twenty feet below the 5-foot-thick concrete shield. By means of a remotely controlled mirror, the operator could direct light rays from a 21-foot periscope, called an Omniscope, into the Questar, where visual or photographic images were formed at will. Inside the empty tank the radiation level sometimes reached 100,000 roentgens per hour, a small fraction of which would be lethal.” The Questar made both photographic imaging and visual observation possible. “It was nice to hear that a standard Questar, without any modification at all, had proved to be so useful in this most exacting application.”[73]

Other government agencies and branches of the armed forces made use of Questar telescopes for unusual projects by the early 1960s. The Naval Air Development Center at Johnsville, Pennsylvania, used a Questar for aerial surveillance. An engineer from Fort Monmouth informed Questar how pleased he was about the performance of the Questar he and his colleagues used for photography. And the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had acquired several Questar telescopes.[74]

Critical Praise

Critics recognized the Questar telescope as a fine example of midcentury American innovation and design.

In his book American Design in the Twentieth Century: Personality and Performance, Gregory Votolato wrote that various museums hosted exhibits featuring American industrial products, and they favored items that demonstrated contemporary over traditional design. With the intention of “elevating consumers’ tastes in domestic products,” the “Good Design” exhibitions began at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1951 under the direction of curator Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., and his jurors. Other shows emerged in short order. One was entitled 20th Century Design: U.S.A. by the Albright Art Gallery of Buffalo, New York. Organizers of the exhibit featured objects with “design maturity,” in the words of Le Corbusier. The deciding criteria were simple: “performance, durability, form.”[75]

The Questar telescope demonstrated all of these characteristics. In its advertisement that appeared in the March 1959 issue of Sky and Telescope, the company announced that its product would appear in 20th Century Design: U.S.A.[76] It continued to do so in Natural History and Scientific American magazines through October.[77]

Between 1962 and 1964, a Questar telescope also appeared in the United States Information Agency’s World Science and the U.S.A. exhibit.[78]

The press took note of Questar, too. In their issue of May 23, 1964, the editors of the Saturday Review turned to noted industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague, the “dean of industrial design,” to identify the top creative examples of the era. In his article entitled “The Twenty Best Industrial Designs Since World War II,” Teague made his selection. Listing them in the order by which they occurred to him, he recognized a wide variety of international products that were both mundane and extraordinary: automobiles, sports equipment, aircraft, electronics, a paper towel holder, and even a toilet. The tenth item on his list was the Questar telescope, which, as he wrote, was “another answer to the person who says we can’t produce fine craftsmanship in the U.S.A. Designed and built in the little Pennsylvania town of New Hope, this beautiful little telescope is the finest instrument of its kind in the world.”[79]

More specialized publications also began noticing the Questar. After Modern Photography published its test report on the Standard Questar in August 1962,[80] Camera 35 magazine followed with its own general writeup of mirror telephoto lenses in its August-September 1963 issue. Beginning with a brief summary of the history of telescopes including Galileo’s refractor, Newton’s reflector, and Schmidt’s catadioptric camera, writer Arthur Kramer then discussed offerings by Nikon, Zeiss, and Zoomar. “For those interested in astronomy,” Kramer added, “the Questar would be a superb choice in terms of outstanding performance and remarkable ease of use.” It offered one advantage the others lacked: the use of an eyepiece for visual observation. And compared to equivalent telephoto mirror lenses by other companies, Kramer pointed out that the $995 cost for a Questar was not bad especially considering the buyer received a complete telescope for that price.[81]

The Questar telescope also made appearances in numerous books. In his 1962 work Complete Book of Nature Photography, Russ Kinne suggested using what he described as “the incomparable Questar” for both long-range and close-up nature photography. In his acknowledgements, he also thanked Lawrence Braymer, who surely had more than a few things to say to the writer in favor of his telescope.[82] In two books, Outer Space Photography for the Amateur (1960) and Telescopes for Skygazing (1965), Henry Paul described how useful Questar telescopes were for all kinds of astronomical observing and photography, and he even made extensive use of Questar’s own marketing photographs throughout both works.[83] In a reciprocal gesture, Braymer promoted Paul’s later book in his advertisement appearing in the December 1966 issue of Sky and Telescope. No doubt aware of how prominently the Questar telescope appeared in it, Braymer naturally characterized Telescopes for Skygazing as “an indispensable book for the amateur astronomer.”[84] And in 1971, Questar made an appearance as an example of a modern Cassegrain telescope in a children’s book by Roy Worvill entitled How It Works: The Telescope and Microscope.[85]

Popularization of the Maksutov-Cassegrain Design

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then the degree to which the Questar telescope spurred others to adopt the basic Maksutov-Cassegrain design was perhaps the most telling indication of the company’s success and influence.

Amateur Telescope Makers

Suggesting that the Questar was no product of the amateur telescope maker, Lawrence Braymer wrote in his July 1956 advertisement in Sky and Telescope that his company’s product “is mighty hard to make—nobody makes this one on the kitchen table.” Indeed, it’s “tough to make, but it’s a tough little, sharp little telescope—it’s a Questar!”[86] While they probably did not make their instruments on kitchen tables, amateur telescope makers nonetheless proved that the Maksutov-Cassegrain design was within their reach. Later that year, the first signs emerged in Sky and Telescope that ATMs had taken interest in building these telescopes themselves.

In the September 1956 issue of Sky and Telescope, columnist Earle B. Brown opened the last installment in a 21-part series entitled “Notes on Basic Optics” by acknowledging the increased popularity of catadioptric telescopes. Recognizing the designs of Dmitri Maksutov and Albert Bouwers, Brown wrote that “systems of this type are now on the market as long-focus or telephoto camera lenses.” Assessing possibilities for the amateur telescope maker, Brown added that shaping the spherical surfaces of the corrector lens on Maksutov-style telescopes was much easier at least for professional shops than producing the aspheric corrector plate of Schmidt’s design. On the other hand, obtaining a piece of optical glass for the thick and deeply curved meniscus lens may have represented a prohibitive cost for the average amateur.[87]

In spite of its challenges, Maksutov’s design made a splash at the August 1956 Stellafane convention near Springfield, Vermont. In its report on the gathering in its October 1956 issue, Sky and Telescope announced the formation of a “Maksutov club” as one indication of the clear interest that amateur telescope makers had expressed in the design. The magazine advised its readers to write the group’s founder, Alan Mackintosh, for information on the availability of materials and for designs from James G. Baker, who had delivered a lecture on the Maksutov design at the convention and who distributed specifications for non-commercial use by amateurs.[88]

In the March 1957 issue of Sky and Telescope, “Gleanings for ATM’s” columnist Robert E. Cox noted that “interest in telescopes of the Maksutov type of amateur use is increasing rapidly.” By that stage, Mackintosh’s Maksutov club had about 200 correspondents who had registered since it was announced at the Stellafane convention.[89]

In the same column, John Gregory, who had won first prize for observing performance at Stellafane for his five-inch Maksutov telescope,[90] published his milestone article “A Cassegrainian-Maksutov Telescope Design for the Amateur.” It only added to a growing sense of enthusiasm for Maksutov’s catadioptric design.

Echoing Braymer’s argument that the Questar was the successor to old-style refractors and reflectors, John Gregory wrote that he built a 5-inch Maksutov telescope whose “convenience, ease of transporting and observing, far outclasses the old-fashioned reflector or refractor. My own 4-inch refractor is now in moth balls.” Addressing those who may have been deterred by this supposedly special design, one that cost “upwards of a thousand dollars when commercially made”—there was little doubt about exactly which commercial telescope he referred to—Gregory offered encouragement to his readers. “If you are an average ATM,” he wrote, “you can fabricate the parts yourself.” Perkin-Elmer, Gregory’s employer, had produced a triple-element Maksutov-Cassegrain instrument based on James G. Baker’s design, one that was well-corrected for coma and astigmatism. “However, for visual use and small-field photography (half a degree), the two-element design I have used makes a fine telescope with several advantages over refractors and reflectors of equal aperture.” The design included an aluminized secondary spot on the inside surface of the corrector lens. It also lacked a secondary spider support that would otherwise have introduced diffraction spikes, was free of contrast-robbing color fringing, and reduced negative thermal effects thanks to its closed tube.[91]

Gregory’s design included a spherically-figured corrector lens and primary mirror. The negative spherical aberration of the corrector balanced the positive spherical aberration of the primary mirror. In spite of the relative simplicity of the optical surfaces, however, one must not be led “into thinking that the figuring tolerances are loose. The surfaces must be well figured if the telescope is to give the high performance inherent in the design.” He provided dimensions for an instrument with a six-inch corrector lens proportioned to f/15 and f/23, and he pointed out that “the surfaces of the corrector lens, R1 and R2, may vary together from the design by as much as 0.07" in radius of curvature, but both in the same direction. The variation of R1 should equal that of R2 within 0.004". The primary mirror, however, need be made only within 0.5" of the specified radius of curvature.” Gregory also specified that the smoothness of all surfaces should be one-quarter wave or better.[92] In this respect, he echoed Braymer’s claims about the painstaking difficulty involved in producing Questar’s optics.

While he shared Braymer’s appreciation for the effort it took to make high-quality catadioptric optics, Gregory did not share in his sense of enthusiasm for the Questar telescope. As longtime Questar associate Rodger Gordon noted, John Gregory objected to the Questar’s design due to its placement of the secondary spot on the outside surface of the corrector lens. Gregory went further by disparaging the Questar as a “daytime toy.” But his own telescopes, which Gregory made by means of a side business, were not baffled for daytime use and were thus not as versatile as the Questar.[93]

Regardless of his misgivings, Gregory’s 1957 article was a watershed moment in amateur telescope making. In his obituary for John Gregory, who died suddenly as the result of an automobile accident on November 14, 2009, Sky and Telescope writer Roger Sinnott reflected on the significance of Gregory’s contribution. “No longer was an ever-larger Newtonian reflector the only thing on glass-pushers’ wish lists. Gregory showed how to make a far more sophisticated telescope, not unlike the high-end Questar catadioptric telescope that began to be a commercial rage in the 1950s. John didn’t just provide the curves and specs for an experienced mirror-maker to work to; he presented the shop techniques and exacting tests needed for a successful completion.”[94]

By early 1963, Sky and Telescope had published so many articles on the Maksutov-Cassegrain design in its “Gleanings for ATM’s” column that the publication compiled them into a single volume entitled “Sky and Telescope Bulletin C: Maksutov Articles from Gleanings for ATM’s.” The collection contained twenty-two pieces that had appeared in the magazine’s pages between September 1956 and February 1963 by various authors. The magazine also reproduced Dmitri Maksutov’s article entitled “New Catadioptric Meniscus Systems,” which had appeared in the May 1944 edition of the Journal of the Optical Society of America.[95]

Commercial Manufacturers

If amateurs were adopting the Maksutov-Cassegrain design in their own work, so too were commercial telescope makers. By the early 1960s, other competing manufacturers had begun producing their own telescopes based on the Maksutov-Cassegrain design. One model by Vega Instrument Company appeared to be an early Maksutov-Newtonian design.[96] Other models by Tinsley Laboratories and Thermoelectric Devices, Inc. bore striking resemblance to the Questar but were just different enough to evade patent infringement.[97] And Cell Optical Industries marketed a three-inch Maksutov-Cassegrain mounted on a set of flimsy tabletop tripod legs.[98] Few if any of these competing products matched both the quality and the ingenuity of the Questar telescope.

Occasionally, some manufacturers crossed the line. By the late 1950s, the Questar had become such a success that one even mimicked its name—and it did so at its peril. After J.W. Fecker announced its Celestar telescope at the end of 1956, Questar wasted little time with starting legal proceedings to halt the seemingly obvious infringement on its name.[99]

Ultimately, however, companies in other industries adopted the term Questar. An educational testing company called itself Questar Assessment Incorporated.[100] A gas company named Questar Corporation began operation.[101] A packaging manufacturer simply called itself Questar.[102] A film and television distributor used the name Questar Entertainment,[103] and an imprint of Hachette Book Group dubbed itself Questar Science Fiction.[104]

Manufacturers also used the word Questar for branding specific products. There were Bull Questar computer terminals.[105] Adidas sold Questar shoes.[106] A character named “Questar” even appeared in Dino-Riders, an animated cartoon series first appearing in 1988.[107] The name had proliferated so much that Wikipedia saw the need to create a disambiguation page for the term Questar.[108]

While Lawrence Braymer’s company ultimately failed to block other businesses from using its name, Questar fully embraced the spirit of continual refinement and innovation that drove its founder.

Notes

1 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, May 1958, 360.

2 “Biography of Wernher Von Braun,” Marshall Space Flight Center, n.d., https://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/history/vonbraun/bio.html, accessed December 29, 2020.

3 “Biography of Wernher Von Braun,” Marshall Space Flight Center, n.d., https://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/history/vonbraun/bio.html, accessed December 29, 2020; “Redstone Arsenal,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Redstone_Arsenal, accessed December 29, 2020.

4 “Redstone Arsenal,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Redstone_Arsenal, accessed December 29, 2020.

5 “Redstone Arsenal,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Redstone_Arsenal, accessed December 29, 2020.

6 Kennedy Space Center Amateur Astronomers, “The Story of Dr. Wernher von Braun’s Questar,” n.d., https://kscaa.space/vonbraunquestar, accessed September 30, 2019.

7 “Wernher von Braun,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wernher_von_Braun, accessed December 29, 2020; “Biography of Wernher Von Braun,” Marshall Space Flight Center, n.d., https://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/history/vonbraun/bio.html, accessed December 29, 2020.

8 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1961, 223.

9 Laura Bergquist, “The Curious Story Behind the New Cary Grant,” Look, September 1, 1959, https://www.trippingly.net/lsd-studies/the-curious-story-behind-the-new-cary-grant, accessed December 30, 2020.

10 “Betsy Drake,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Betsy_Drake, accessed December 30, 2020.

11 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1960, 90.

12 “Psycho (1960 film),” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psycho_(1960_film), accessed December 30, 2020; “Anthony Perkins,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Perkins, accessed December 30, 2020.

13 “Berry Berenson,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berry_Berenson, accessed December 27, 2020; “Elsa Schiaparelli,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elsa_Schiaparelli, accessed December 30, 2020.

14 “King Mohammed V, Back from His Visit, Lauds U.S. Leaders; U.S. Aid to Continue,” New York Times, December 16, 1957, https://www.nytimes.com/1957/12/16/archives/king-mohammed-v-back-from-his-visit-lauds-us-leaders-us-aid-to.html, accessed December 12, 2020; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, February 1958, 186; “Mohammed V of Morocco,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohammed_V_of_Morocco, accessed December 30, 2020.

15 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, February 1958, 186.

16 Rodger Gordon in discussion with the author, August 15, 2020. Gordon attributed a sudden increase in the company’s sales to Eisenhower’s gift of a Questar to King Mohammed V during his state visit to the United States in late 1957.

17 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1962, inside front cover; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, April 1962, inside front cover.

18 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, June 1962, 180.

19 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, May 1954, 2-3.

20 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1961, 223.

21 Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer, The Backyard Astronomer’s Guide (Camden East, Ontario: Camden House, 1991), 22, https://archive.org/details/the-backyard-astronomers-guide/page/22/mode/1up, accessed December 20, 2022.

22 Charles Shaw, “Larry Braymer: ‘In Quest of the Stars,’” New Hope Gazette, March 14, 1985, 32, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed October 15, 2019.

23 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Baltimore, Maryland, August 3, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 1-4; “Alfred Hougham Mikesell,” Legacy, n.d., https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/name/alfred-mikesell-obituary?pid=113642858, accessed June 29, 2020.

24 Steven J. Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined: The US Naval Observatory 1830-2000 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 422, https://books.google.com/books?id=DNwfG5hQ7-YC&pg=PA422#v=onepage&q&f=false, accessed July 2, 2020.

25 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Baltimore, Maryland, August 10, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 141.

26 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 146-147.

27 Alfred Mikesell, “The Scintillation of Starlight,” Publications of the United States Naval Observatory 17, part 4 (1955): 139-191, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/ScintillationOfStarlightAHM-USNO.pdf, accessed December 15, 2019.

28 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Baltimore, Maryland, August 10, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 143-144.

29 Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019); Alfred Mikesell, “Discussion of Balloon Trip” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/Discussion_of_flight.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

30 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Baltimore, Maryland, August 10, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 144.

31 “Malcolm Ross (balloonist),” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malcolm_Ross_(balloonist), accessed July 4, 2020; Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 148.

32 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 151.

33 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Baltimore, Maryland, August 10, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 144; Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

34 Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

35 Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

36 Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

37 Alfred Mikesell, “Discussion of Balloon Trip” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/Discussion_of_flight.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

38 Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

39 “Malcolm Ross (balloonist),” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malcolm_Ross_(balloonist), accessed July 4, 2020; Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 150; Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

40 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 161.

41 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 155, 160-161.

42 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 161-163.

43 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 163-164; Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

44 Alfred Mikesell, “Observations of Stellar Scintillation from Moving Platforms,” Astronomical Journal 63 (1958): 309, http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1958AJ.....63R.308M, accessed July 2, 2020.

45 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 149; Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019); “Malcolm Ross (balloonist),” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malcolm_Ross_(balloonist), accessed July 4, 2020.

46 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 164-165.

47 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 164.

48 “Space Explorers Rise Nearly 8 Miles in a Balloon; 2 in Balloon Soar to 40,000 Feet; Find Stars Don't Twinkle There,” New York Times, May 8, 1958, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1958/05/08/83412955.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0, accessed July 4, 2020.

49 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, July 1958, 463.

50 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 149.

51 Gregory Kennedy, “Stratolab, An Evolutionary Stratospheric Balloon Project,” StratoCat, February 25, 2018, http://stratocat.com.ar/artics/stratolab-e.htm, accessed July 2, 2020.

52 Alfred Mikesell, “Slideshow Narration” (presentation, n.d., recorded by Stephen Mikesell, http://www.mikesell.info/audio/balloon_talk.mp3, accessed December 15, 2019).

53 Alfred Mikesell, interview by Steven J. Dick, tape recording transcript, Washington, D.C., August 15, 1988, http://www.mikesell.info/pdf/TheAstronomer.pdf, accessed December 15, 2020, 153-155.

54 “The National Academy of Sciences: Abstracts of Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting, April 23-25, 1951,” Science 113, no. 2939 (1951): 483, www.jstor.org/stable/1679257, accessed April 26, 2020.

55 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1961, 223.

56 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1961, 223; “Kenneth Mees,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenneth_Mees, accessed July 9, 2020.

57 John T. Jefferies, “Astronomy in Hawaii, 1964-1970: Beginnings,” University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy, n.d., https://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/users/jefferies/Beginnings.htm, accessed July 9, 2020.

58 John T. Jefferies, “Astronomy in Hawaii, 1964-1970: Beginnings,” University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy, n.d., https://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/users/jefferies/Beginnings.htm, accessed July 9, 2020.

59 John T. Jefferies, “Astronomy in Hawaii, 1964-1970: Planning a Program in Solar Physics,” University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy, n.d., https://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/users/jefferies/Planning_a%20Program_in_Solar_Physics.htm, accessed July 9, 2020.

60 John T. Jefferies, “Astronomy in Hawaii, 1964-1970: Dawn of a Brilliant Opportunity,” University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy, n.d., https://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/users/jefferies/Dawn_of_a_Brilliant_Opportunity.htm, accessed July 9, 2020.

61 John T. Jefferies, “Astronomy in Hawaii, 1964-1970: The Selection of Mauna Kea,” University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy, n.d., https://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/users/jefferies/The_Selection_of_Mauna_Kea.htm, accessed July 9, 2020.

62 John T. Jefferies, “Astronomy in Hawaii, 1964-1970: The Selection of Mauna Kea,” University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy, n.d., https://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/users/jefferies/The_Selection_of_Mauna_Kea.htm, accessed July 9, 2020.

63 “Mauna Kea Observatories,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mauna_Kea_Observatories, accessed July 10, 2020.

64 John T. Jefferies and William M. Sinton, “Progress at Mauna Kea Observatory,” Sky and Telescope, September 1968, 140-145.

65 “Mauna Kea Observatories,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mauna_Kea_Observatories, accessed July 10, 2020.

66 E. Brosterhus, E. Pfannenschmidt, and F. Younger, “Observing Conditions on Mount Kobau,” Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 66, no. 1 (1972): 14, https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu//full/1972JRASC..66....1B/0000014.000.html, accessed February 4, 2022; J. H. Hodgson, The Heavens Above and the Earth Beneath, A History of the Dominion Observatories: Part 2, 1946 to 1970 (Geological Survey of Canada, 1989), 235, https://www.mksp.ca/pages/history/KobauHistory.pdf, accessed February 4, 2022; “Mount Kobau National Observatory,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Kobau_National_Observatory, accessed February 4, 2022.

67 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1960, 386.

68 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1959, 294; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1961, 223.

69 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, May 1954, 9-10.

70 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, September 1960, 260.

71 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, May 1958, 360.

72 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, October 1958, 9.

73 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, July 1961, 68.

74 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1961, 223.

75 Gregory Votolato, American Design in the Twentieth Century: Personality and Performance (Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press, 1998), 52, https://books.google.com/books?id=EwOcmmnxKbwC, accessed June 17, 2020.

76 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1959, 294.

77 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, October 1959, 178.

78 Questar Corporation, “On the Problem of Choosing a Telescope,” 1973.

79 Walter Dorwin Teague, “The Twenty Best Industrial Designs Since World War II,” Saturday Review, May 23, 1964, 17, http://www.company7.com/library/questar/notes.html, accessed September 20, 2019; “Walter Dorwin Teague, FIDSA,” Industrial Designers Society of America, 2020, https://www.idsa.org/content/walter-dorwin-teague, accessed August 7, 2020.

80 Herbert Keppler and Bennett Sherman, “Questar: 1125mm of Lens Weighs 6.7 Lbs,” Modern Photography, August 1962, 94-95.

81 Arthur Kramer, “A Complete Report on Mirror Optics,” Camera 35, August-September 1963, 30-33, 60, https://mikeeckman.com/2020/04/kepplers-vault-61-mirror-lenses/, accessed June 27, 2022.

82 Russ Kinne, The Complete Book of Nature Photography (New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1962), https://archive.org/details/lccn_62010991/, 8, 22, 59, 122 accessed June 4, 2022.

83 Henry E. Paul, Outer Space Photography for the Amateur (New York: American Photographic Book Publishing Co. Inc., 1960, third edition, 1967), https://archive.org/details/outerspacephotog00paul/mode/2up?q=Questar, accessed June 7, 2022; Henry E. Paul, Telescopes for Skygazing (New York: American Photographic Book Publishing Co. Inc., 1965), https://archive.org/details/telescopesforsky0000paul/mode/2up?q=Questar, accessed June 4, 2022.

84 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, December 1966, inside front cover.

85 Roy Worvill, How It Works: The Telescope and Microscope (Loughborough: Wills and Hepworth, 1971), 23; Roger Vine, “Questar 3.5 Review,” n.d., http://scopeviews.co.uk/Questar35.htm, accessed June 4, 2022.

86 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, July 1956, 420-421.

87 Earle B. Brown, “Notes on Basic Optics—XXI,” Sky and Telescope, September 1956, 511-512.

88 “Convention in Vermont,” Sky and Telescope, October 1956, 533; Gary Leonard Cameron, “Public Skies: Telescopes and the Popularization of Astronomy in the Twentieth Century,” PhD diss., (Iowa State University, 2010), 246-247, https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11795/, accessed September 30, 2019.

89 Robert E. Cox, “Gleanings for ATM’s,” Sky and Telescope, March 1957, 238.

90 “Convention in Vermont,” Sky and Telescope, October 1956, 533; Gary Leonard Cameron, “Public Skies: Telescopes and the Popularization of Astronomy in the Twentieth Century,” PhD diss., (Iowa State University, 2010), 246, https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11795/, accessed September 30, 2019.

91 John Gregory, “A Cassegrainian-Maksutov Telescope Design for the Amateur,” Sky and Telescope, March 1957, 236.

92 John Gregory, “A Cassegrainian-Maksutov Telescope Design for the Amateur,” Sky and Telescope, March 1957, 236-238.

93 Rodger Gordon in discussion with the author, August 15, 2020.

94 Roger W. Sinnott, “In Memoriam: John Gregory,” Sky and Telescope, November 19, 2009, https://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/in-memoriam-john-gregory, accessed December 28, 2019.

95 Sky Publishing Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1963, 228.

96 Vega Instrument Company, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, January 1962, 51.

97 Tinsley Laboratories, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, May 1963, 271; Tinsley Laboratories, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, October 1963, 221; Thermoelectric Devices, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1964, 90.

98 Cell Optical Industries, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, November 1964, 300.

99 Gary Leonard Cameron, “Public Skies: Telescopes and the Popularization of Astronomy in the Twentieth Century,” PhD diss., (Iowa State University, 2010), 232, https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11795/, accessed September 30, 2019. Offering evidence that Lawrence Braymer was in direct contact with Albert Ingalls, Cameron cites a letter from Braymer to Ingalls dated December 12, 1956 (Albert G. Ingalls Papers, Archives Center of the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History, box 5, folder 6).

100 Home page, Questar Assessment Inc., 2017, http://www.questarai.com, accessed December 31, 2020.

101 “Questar Corporation (gas company),” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Questar_Corporation_(gas_company), accessed December 31, 2020.

102 Home page, Questar, LLC, n.d., http://questarusa.com, accessed December 31, 2020.

103 Home page, Questar Entertainment, n.d., https://www.questarentertainment.com, accessed December 31, 2020.

104 “Hachette Book Group,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hachette_Book_Group, accessed December 31, 2020.

105 “Bull Questar,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bull_Questar, accessed December 31, 2020.

106 Search results, adidas, n.d., https://www.adidas.com/us/search?q=questar, accessed December 31, 2020.

107 “Dino-Riders,” Wikia.org, n.d., https://dino.wikia.org/wiki/Dino-Riders, accessed December 31, 2020.

108 “Questar,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Questar, accessed December 31, 2020.