How I Make Photographs, by Joel Meyerowitz

November 15, 2023

Tags: Photography, Book Reports

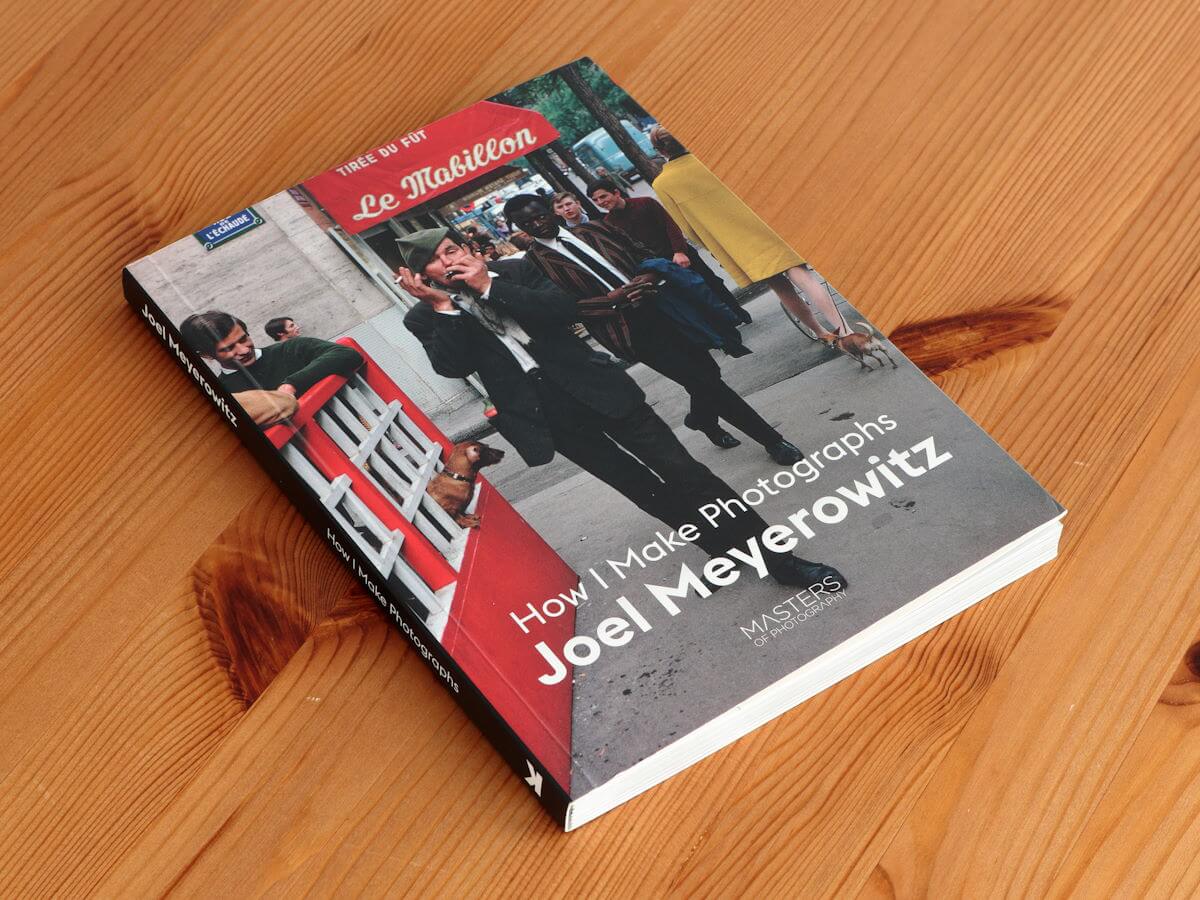

A while back I picked up a copy of Joel Meyerowitz’s 2019 book How I Make Photographs at Powell’s Books in Portland. This great little book was actually sitting on a shelf of discounted books. But I would have been happy to pay full price for it considering how thought provoking it is.

“Joel Meyerowitz is one of the most celebrated street photographers of his generation,” trumpets the blurb on the back cover inside flap. And he does indeed offer a ton of great advice to practitioners of that genre of photography. Meyerowitz tailors all of his book’s chapters around a tightly-conceived theme or suggestion, and many of those deal specifically with the challenges of street photography: “Own the Street,” “Embrace the Everyday,” “Anticipate the Moment,” and “Make Connections” are the titles for the third through sixth of the book’s twenty chapters.

But beyond street photography, Joel Meyerowitz offers something to every kind of photographer. He opens his book with a chapter entitled “Discover Your Identity as an Artist.” Along with the next chapter entitled “Be Inspired,” where he encourages his reader to let other photographers’ work spark creativity in one’s own work, Meyerowitz echoes themes I encountered in Andreas Feininger’s The Complete Photographer, namely the importance of establishing one’s own unique character as a photographer.

A sense of exploration and inexhaustible curiosity about the world drives Meyerowitz’s book. The camera, in a sense, becomes the mere vehicle by which the photographer learns more about the world and himself. “The way I see it,” Meyerowitz writes, “photography is like putting a key in a door, opening it, and seeing the world suddenly come alive” (p. 61).

I also appreciate Meyerowitz’s emphasis on trusting one’s gut. Although one needs technical competence, doing photography is not a matter of executing canned formulas. At that split-second moment when you decide to press the shutter button, an inner sense of what makes a compelling image should be the driver. It can’t be taught. It’s in all of us. Meyerowitz encourages his reader to trust that sense and develop it.

I’m guilty of being fascinated by camera gear. Maybe I shouldn’t feel guilty about that. Whatever the case may be, I know that camera gear exists to be used. Its purpose is to make images. As such, it’s important to find gear that feels comfortable. Here, too, Meyerowitz makes a compelling case. He puts particular emphasis on one’s choice of lens. After expressing what draws him in particular to wider-angle lenses, Meyerowitz turns the question back to the reader. “My most important technical advice is to find a lens that suits your personality.” Find a lens that matches how you see the world and stick with it. Don’t change lenses constantly. Be disciplined and stick with a single prime lens. “Trust me on this. Pick a lens that feels right, and if it makes you feel frustrated, change it” (p. 82). The simple and ubiquitous “nifty fifty” lens and short telephotos have, for me, become those windows I feel most comfortable using. They allow me to record how I see the world without getting in the way.

After offering some suggestions for composition, Meyerowitz encourages his reader to be courageous, push beyond personal limits, and seek out opportunities that may feel uncomfortable but that make one grow in the end.

One of my favorite chapters in How I Make Photographs is the one Meyerowitz entitled “Photography Is About Ideas.” After having spent recent years moving beyond mere snapshot shooting and becoming a more serious photographer, I’ve reflected on why I do what I do. After admitting it took him time to develop and evolve as a photographer, Meyerowitz drives home an important point. “Photography looks like pictures, but it’s really about ideas. And they’re your ideas; they are unique to you.”

He then asks a direct question: “What do you want to say?” (p. 103).

That is exactly the question that’s been on my mind lately. As I write this, I have well over 6000 images in my catalog from these past two years. That level of production is far beyond the yield of prior years when my photography practice had a more casual pace. What exactly am I trying to say with all those images?

This question doesn’t require a pompous artist’s statement to answer. Posing as expressions of profound insight, such statements more often come across as contrived gobbledygook that are ultimately meaningless. But an awareness of the elements that make one’s best work what it is still has value. Articulating what those elements are can be a challenging exercise, but it is often rather revealing.

And here the importance of culling and editing one’s work emerges, something that Meyerowitz explores at the end of his book.

In one passage, Meyerowitz reflects on one experience he had reviewing a collection of his images. After looking at hundreds of photographs, he realized that a certain theme—flowers—appeared again and again in his work. He eventually tailored an entire book, Wild Flowers (1983), around that theme:

This was a subject that popped up for me out of the editing process. So if you are searching for something new, take a journey into your own interests first. Look at the work you already have and see what it is you’ve hit on again and again. Your subject has identified itself already; it’s just that you may not have recognized it yet, and that’s your responsibility (p. 106).

Recently I’ve been doing a fair amount of editing myself. (To be clear, when I refer to “editing” I mean paring down my mass of images and identifying photographs that have more stopping power than others, not post-production editing using software like Photoshop. I’ve come to believe that no amount of post-production work will make a bad composition into a good one.) One trend I’ve noticed in my own work is one that I’ve noted in the recent past: even though I admire photography of people, I’m not really a people person. The cynical side of my personality sees a certain loneliness that characterizes life today, and I’ve been exploring that theme more consciously in my photography.

I also like portraying urban grit especially when oblique light underscores it. Black and white film in particular allows me to do all of this more effectively. I’m not trying to make any kind of groundbreaking statement here. I just like the look of it.

All of this is to say that reading Joel Meyerowitz’s How I Make Photographs gave me a good boost to continue improving my photographic practice. Buying my copy required only a small financial investment on my part, but there’s no doubt in my mind that it gave far more back to me.