Chapter 5. Expansion into New Product Areas

In This Chapter

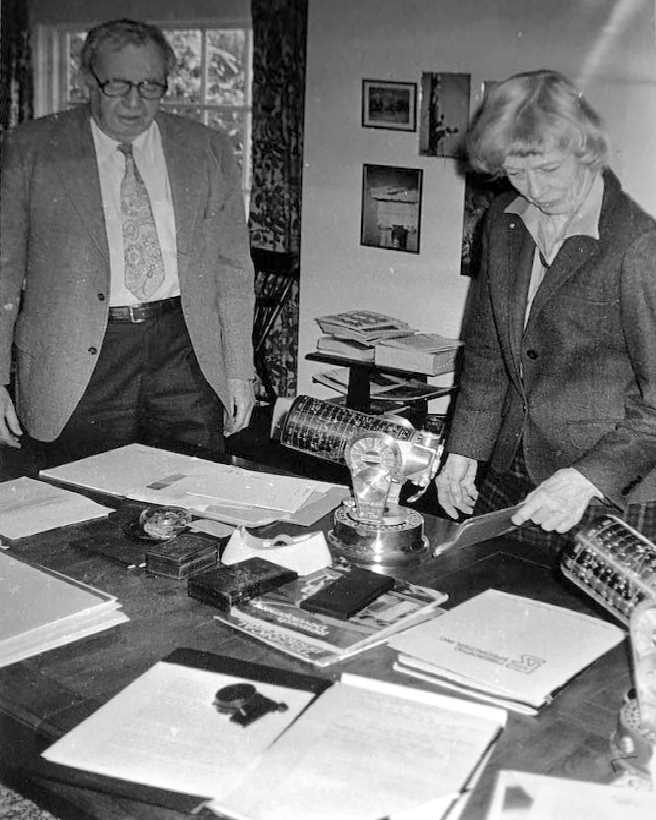

Twenty-five years after she and Lawrence celebrated their nuptials and incorporated their business, Marguerite Braymer looked back at everything that had happened. The couple had succeeded in building a successful business that manufactured and sold one of the finest small telescopes available to amateurs and professionals alike. For the last ten years, she had guided the company by herself in the absence of her husband, who had passed away in December 1965.

It was the beginning of 1976 now. In March, she would reach the age of 65. Looking forward, she began to sense that perhaps the time had come for a change.

When Marguerite met Douglas Knight at a social gathering that she happened to attend while she was participating in an education conference, that feeling coalesced into something more definite. She realized that she could use some assistance, but she did not want to settle for anything except the best. Before long, Marguerite came to believe that Knight represented just that.[1]

At first, “Peg asked me if I could look at the educational aspects of Questar,” Knight later remembered. “I agreed. Then she asked me to become a director of the company. The more I learned about Questar and its many applications, the more excited I became. And when Peg asked me to take over the presidency in 1976, I readily accepted.” When Knight stepped in, Marguerite Braymer became the company’s chairwoman and continued to direct its advertising.[2] Meanwhile, her son Peter Dodd, who had been working at Q Camera in Daytona Beach, Florida, for the past few years, eventually assumed the title of vice president.[3]

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1921, Douglas Maitland Knight demonstrated his academic capabilities by earning a doctorate in eighteenth-century English literature from Yale University in 1946. He was only in his mid-twenties at the time. With a special interest in the poetry of Alexander Pope and his translations of Homer, he stayed at Yale and eventually earned tenure there. In 1954, Knight moved on to Lawrence College in Appleton, Wisconsin, and became its president. At 32 years old, he was the youngest person in the United States to hold such a position. Other institutions took notice. In 1962, Duke University convinced Knight to become its president, and he remained there until he resigned in 1969 in the wake of student unrest. Avoiding subsequent academic leadership positions, Knight instead moved into the world of business. He became vice president for education development at RCA Corporation and, in 1971, president of RCA Iran.[4]

When she met him in 1976, Knight was a former academic who had worked in a commercial environment only for a handful of years. But what interested Marguerite Braymer most was his multitude of contacts in education. He held a long list of honors including memberships in numerous educational commissions and other organizations. She reasoned that tapping into Knight’s network might increase Questar’s sales in this market.[5]

In a revision to the company’s promotional booklet that appeared the year after he was hired, it was probably Douglas Knight who wrote about Questar’s place in schools and colleges. He wrote that, on top of serving the three most common objectives of an educator—to open students’ minds, to advance scientific study, and to teach approaches to performing research—a Questar telescope “is more than a service to education: it is an education in itself.”[6]

As if to suggest that the company had neglected to attend to its role in education—in reality, it had not—he drew upon his scholarship in English literature as he continued to make his case:

We haven’t always emphasized this aspect of Questar, since naturally we know that our primary job is to help students look through the telescope at the universe outside. But at the same time we think they should look into it, at the universe inside. The lens system is, as John Donne said of himself, “a little world made cunningly.” It is an introduction to the importance of fine optics in today’s technology, and just as naturally, it is an introduction to the use of metals in modern precision engineering.[7]

Students learn best when they have something in hand, Knight went on to say, and the Questar telescope has its great impact upon students in this way. It introduces them in particular to quality and precision, two elements that could not be separated. “In that discovery they see at first hand the reason for certain kinds of discipline: quality comes only from work designed to produce the finest possible result. And that pleasure in excellence is a great aesthetic encounter.”[8]

After his arrival at Questar, Douglas Knight settled into an office lined with Chippendale furniture and antique telescopes. Its walls displayed photographs of wildlife and astronomical objects that owners had taken with their telescopes and sent in to the company.[9]

Knight joined a lively cast of characters who had long ensconced themselves in the work of handcrafting Questar’s products. Their slow and deliberate effort made sure that demand always exceeded the company’s rate of production.[10]

During his visit to Questar one day in the late 1970s, Photomethods writer Mark Sherman ventured into the company’s workshop. He had never seen an optical assembly shop before, and he expected to see a cold and sterile production environment. Upon opening the door, he instead found a large, well-lit, and pleasant work area filled with the sound of soft rock music coming from a radio. With test equipment on their flanks, two rows of workbenches held “a clutter of main housings, mirror thimbles, barrel components and corrector lenses.”[11]

“It is the lunch hour,” Sherman wrote, “and the shop has been deserted by all but one of the technicians. He sits at his felt-covered work table tinkering with a partially-assembled mirror lens. He turns the unit over in his hands repeatedly, feeling the focusing action for high spots or irregularities. Every so often he adjusts tiny screws recessed into the barrel mount. Time seems of little importance to him. It is a scene designed to quickly send a volume-conscious plant manager into cardiac arrest.”[12]

After lunch, activity in the shop resumed. Sherman soon spotted Walt Everett at work. When he was not attending to his part-time responsibilities at Questar—or when he received a call and had to leave the shop suddenly—Everett was on patrol with the New Hope Police Department, where he was employed full time. But on the day of Sherman’s visit, he was busy at Questar’s infinity collimator, a 22-foot-long tunnel that the company still uses to make adjustments to the optical alignment of each instrument it produces. “It is the most critical stage in the assembly process, and minute adjustments made by the technician seem endless. A full 15 minutes pass before he is satisfied with the centering. Finally, he removes the lens from its cradle, attaches a new one, and begins again.”[13]

Walt Everett was not the only staffer at Questar to work for local emergency services. Bob Forbes had a part-time job as a police officer in addition to his full-time work at Questar. And Dale Ott, the company’s shop foreman who also worked on special projects and who helped build and test Questar 700 lenses, was an active volunteer firefighter. As soon as he heard the blare of an alert from his pager, he set aside whatever he was doing and rushed to get to a fire truck.[14]

Elsewhere in the assembly process, other workers contributed their part. Watching over his work with intense focus, Brant Adams cleaned optics and handled the assembly and final testing of Questar’s fork mount bases. With an occasional smile showing through the thick layer of rough stubble that always covered his face, he enjoyed a good joke, liked his whiskey, and was not shy about having a lit cigarette next to him as he worked. Outside of work, Adams dabbled as an amateur gemologist who cut and polished diamonds and made jewelry on the side. Upon his retirement, he moved to Sri Lanka and pursued his hobby in earnest.[15]

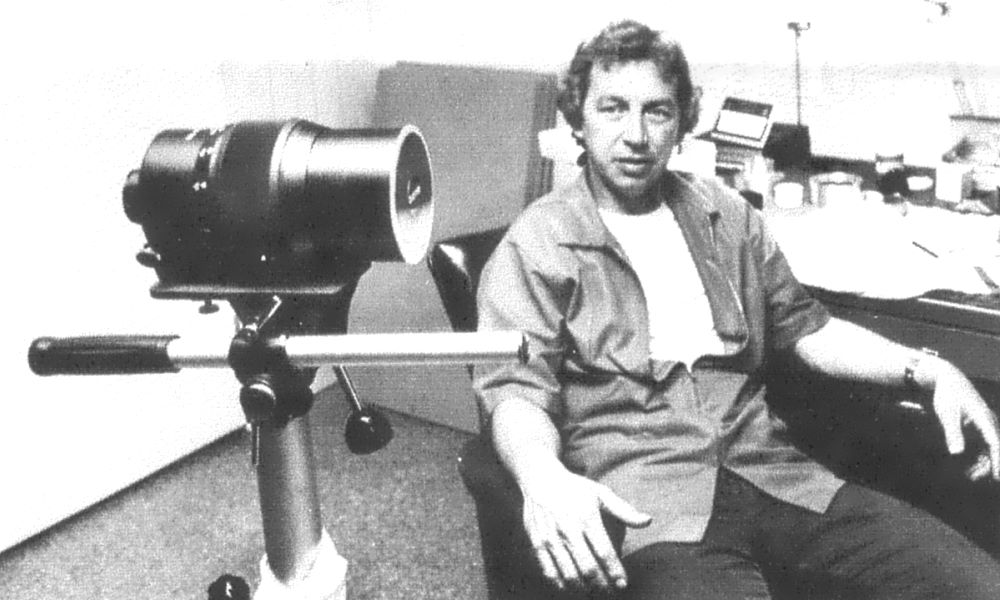

As Brant Adams did his work, Terry Cicchino performed duties that ranged from de-wobbling telescope mirrors to producing electrical accessories including the original Powerguide. Passionate about photography, he became the point person for assembling Questar 700 lenses. He could also be frequently seen with his camera taking pictures all around New Hope, and he used the company’s dark room to develop his film. Cicchino’s workmates were devastated to find him one day in 1996 after he died suddenly of a heart attack. A pall hung over Questar for weeks if not longer.[16]

Another staff member, Conrad Krulle, started his work as a young man at Questar not long after Douglas Knight’s arrival at the company in 1976. Krulle’s responsibilities included machining parts before sending them to the production room for assembly. Later, he picked up work putting together electronic components and Questar’s long-distance microscopes.[17]

In charge of the assembly process and final inspection, Charlie Turn also took care of paperwork and made sure that each unit was ready to be shipped to its eagerly-awaiting customer.[18]

Along with his other duties, Charlie Turn mentored another young addition to Questar, Jim Perkins. Since 1971, he had enjoyed a close friendship with Jim Reichert, Jr., whose father, Jim Reichert, Sr., had worked for Questar since the beginning of the 1960s if not earlier. In May 1978, Perkins was a 21-year-old student at Spring Garden College, a private technical school in the Philadelphia area. He arrived at Questar that month for a summertime job. He never left the company.[19]

Perkins got his start working full eight-hour work days in the company’s shipping room. Making $3 an hour—the federal minimum wage was $2.65 in 1978—his daily duties included making regular 9 am and 3 pm trips to the post office. At the time, carriers’ routes did not include Questar’s rural location outside of New Hope. With the company’s Plymouth station wagon fully loaded, he dropped off shipments and picked up incoming mail.[20]

Since he was studying architecture at Spring Garden College, Perkins had additional drawing and mechanical engineering skills to offer Questar. Demonstrating a keen ability to pick up and understand new ideas, he put in overtime hours after he finished his work in the shipping room so that he could make full use of the company’s full-size drafting table.[21]

Before long, Jim Perkins began to move up in the company. His second job at Questar was in the shop, where he cleaned, waxed, and polished every unit, put them in their cases, and took them to Charlie Turn for final inspection and paperwork. Later, he taught Perkins how to inspect, install, and align telescope optics, his third job at the company.[22]

By 1980, the additional experience that Perkins gained at the drafting table began to pay off. Making frequent trips to one of Questar’s suppliers, Q Machinery, he had increasingly close contact with its owner, master machinist Robert Schwenk. The two eventually formed a close friendship. Sometimes when he received drawings from Perkins for new metal parts, Schwenk tapped his deep experience as a tool and die maker and engaged Perkins as a mentor. Then the instruction would begin. “No,” Schwenk would say, “this is too thin.” “No,” he said at other times, “those threads are wrong.” And again: “No, that would be too costly.” Sometimes, Perkins went too far with his drawings and succeeded only in drawing an incredulous reaction from Schwenk: “Are you kidding me? That can’t be made!” But in the end, Perkins learned a tremendous amount from Schwenk, and he formed an enduring sense of respect for his mentor’s abilities.[23]

Over time, Jim Perkins became Questar’s vice president for operations.[24] But he remained a familiar and friendly voice on the other end of the line when countless Questar owners called the company with a question about their telescopes.

As work in Questar’s assembly shop proceeded in the late 1970s and into the 1980s, Marguerite Braymer took advantage of her new-found time after Douglas Knight’s hiring to pursue other activities. Between 1982 and 1984, she worked as a member of the Small Business Task Force in Washington. And in 1985, she received the Business Achievement Award from the Central Bucks Chamber of Commerce.[25]

Marguerite also engaged in cultural philanthropy. Her hobbies had always included reading and music, and in 1973 she had already become a trustee of the New School of Music in Philadelphia. In 1980, she formed the Questar Library of Science and Art on her property at Stoney Hill Road in Solebury, just south of Questar’s headquarters. The next year, she incorporated it as a foundation, and she opened it to the public in 1984. In time, the organization absorbed the personal libraries of both Marguerite Braymer and Douglas Knight, received other donations from friends, and even added a librarian, Ben Turner. The library’s collection eventually grew to almost 7000 volumes covering fine arts, science, architecture, antiques, biography, and history. And in 1990, Marguerite Braymer added to her cultural resume by becoming a trustee of the Bucks County Historical Society.[26]

In a number of areas, the mid- to late 1970s marked a turning point for Questar. A seemingly small but nonetheless significant optical design change represented the closure of a story that had begun in the earliest days of Lawrence Braymer’s design work in the late 1940s. Questar also introduced—or thought about introducing—new products whose lifespan was not quite as long as the company may have hoped. More significant was its deeper movement into the special applications market. With continued research advancements in areas that ranged widely from scientific pursuits to military purposes, Questar did its best to keep pace with current trends.[27]

Forces outside of Questar’s control also exerted their influence on the direction of the company. As the 1970s and 80s progressed, rivalries grew more intense. Once source of competition proved to be short lived while another posed a more persistent challenge.

The company’s now famous marketing proceeded along its steady course, but the task of selling the Questar was getting harder. Still, the telescope’s adoption and influence were apparent as even more celebrities becoming owners of them. A few of Questar’s products even made an appearance in movies.

Notes

1 Charles Shaw, “New Hope’s Questar: A Quiet Company,” New Hope Gazette, March 21, 1985, 14, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed October 15, 2019.

2 Charles Shaw, “Larry Braymer: ‘In Quest of the Stars,’” New Hope Gazette, March 14, 1985, 32, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed October 15, 2019.

3 A business card attached to some pieces of Questar promotional literature show that Peter Dodd had become a vice president of company.

4 Questar Corporation, “Douglas Maitland Knight,” n.d., http://www.questarcorporation.com/dknight.htm, accessed November 6, 2019; “President Douglas M. Knight Resigns from Lawrence,” The Lawrentian (Appleton, Wisconsin), November 2, 1962, 1, https://lux.lawrence.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3390&context=lawrentian, accessed December 11, 2019; “Douglas Knight,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Knight, accessed April 23, 2020; “Lawrence University Presidential Portraits: Douglas M. Knight, President, 1954-1963,” Lawrence University, n.d., https://lux.lawrence.edu/presidentialportraits/6/, accessed December 11, 2019; “Douglas M. Knight, Fifth Duke President, Dies at 83,” Duke University, January 23, 2005, https://today.duke.edu/2005/01/knight_0105.html, accessed December 11, 2019.

5 Rodger Gordon to the author, September 23, 2020; Charles Shaw, “New Hope’s Questar: A Quiet Company,” New Hope Gazette, March 21, 1985, 14, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed October 15, 2019.

6 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1977, 22.

7 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1977, 22.

8 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1977, 22.

9 Mark Sherman, “Quality Craftsmanship: Photomethods Visits Questar,” Photomethods, March 1979.

10 Mark Sherman, “Quality Craftsmanship: Photomethods Visits Questar,” Photomethods, March 1979.

11 Mark Sherman, “Quality Craftsmanship: Photomethods Visits Questar,” Photomethods, March 1979.

12 Mark Sherman, “Quality Craftsmanship: Photomethods Visits Questar,” Photomethods, March 1979.

13 Mark Sherman, “Quality Craftsmanship: Photomethods Visits Questar,” Photomethods, March 1979; Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 5, 2021.

14 Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 4, 2021; Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 5, 2021.

15 Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 4, 2021.

16 Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 4, 2021.

17 Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 8, 2021.

18 Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 4, 2021.

19 Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 5, 2021; Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 8, 2021; “Spring Garden College,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spring_Garden_College, accessed March 8, 2021.

20 Jim Perkins, email message to author, September 17, 2020; Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 8, 2021.

21 Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 8, 2021.

22 Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 4, 2021.

23 Jim Perkins, email message to author, November 30, 2020; Jim Perkins, email message to author, March 8, 2021.

24 “Jim Perkins,” LinkedIn, n.d., https://www.linkedin.com/in/jim-perkins-8960a628, accessed February 15, 2021.

25 Charles Shaw, “Larry Braymer: ‘In Quest of the Stars,’” New Hope Gazette, March 14, 1985, 3, 32, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed MMMM DD, YYYY; Charles Shaw, “New Hope’s Questar: A Quiet Company,” New Hope Gazette, March 21, 1985, 3, 14, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed MMMM DD, YYYY; Who’s Who in America, 1992-1993 (New Providence: Marquis Who’s Who, 1992), volume 1, 392, https://archive.org/details/isbn_0837901480_1/page/392/mode/1up, accessed June 3, 2022.

26 Charles Shaw, “New Hope’s Questar: A Quiet Company,” New Hope Gazette, March 21, 1985, 14, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed October 15, 2019; Who’s Who in America, 1992-1993 (New Providence: Marquis Who’s Who, 1992), volume 1, 392, https://archive.org/details/isbn_0837901480_1/page/392/mode/1up, accessed June 3, 2022; Herb Drill, “Marguerite Braymer, 85, Questar Corp. co-founder,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 1, 1996, R4, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/21814542/the_philadelphia_inquirer/, accessed October 8, 2019; Questar Corporation, “The Questar Library: A Marguerite Braymer Foundation,” n.d., http://www.questar-corp.com/popups/eventscenter.htm, accessed June 6, 2020.

27 Questar Corporation, “A Brief History,” n.d., https://www.questar-corp.com/QuestarPDF/QuestarHistory.pdf, accessed July 3, 2019.