§ 4.2. New Accessories and Design Refinements

On This Page

After it entered production in 1954, the Standard Questar telescope had not changed much by the late 1960s. Although Lawrence Braymer and his colleagues had introduced a number of design refinements, most of its features and finishes remained largely unaltered over its first decade and a half on the market.

As time went on, however, it was inevitable that more obvious transformations would appear. A number of forces drove this evolution. Changes in the availability of the company’s many suppliers, developments in optical design, and other factors all affected Questar.

The end result was a product that still bore all of the key features of the original but that had enough differences to be readily apparent to someone who placed a Questar built in the mid-1960s next to one produced in the mid-1970s.

The company’s accessory offerings also continued to grow and evolve. Questar introduced new optical products, and it brought about novel ways to mount one’s telescope.

Johnny Carson and the Finder Solar Filter

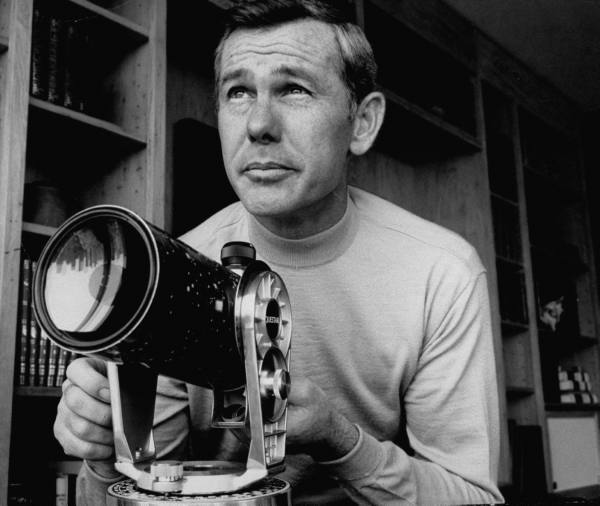

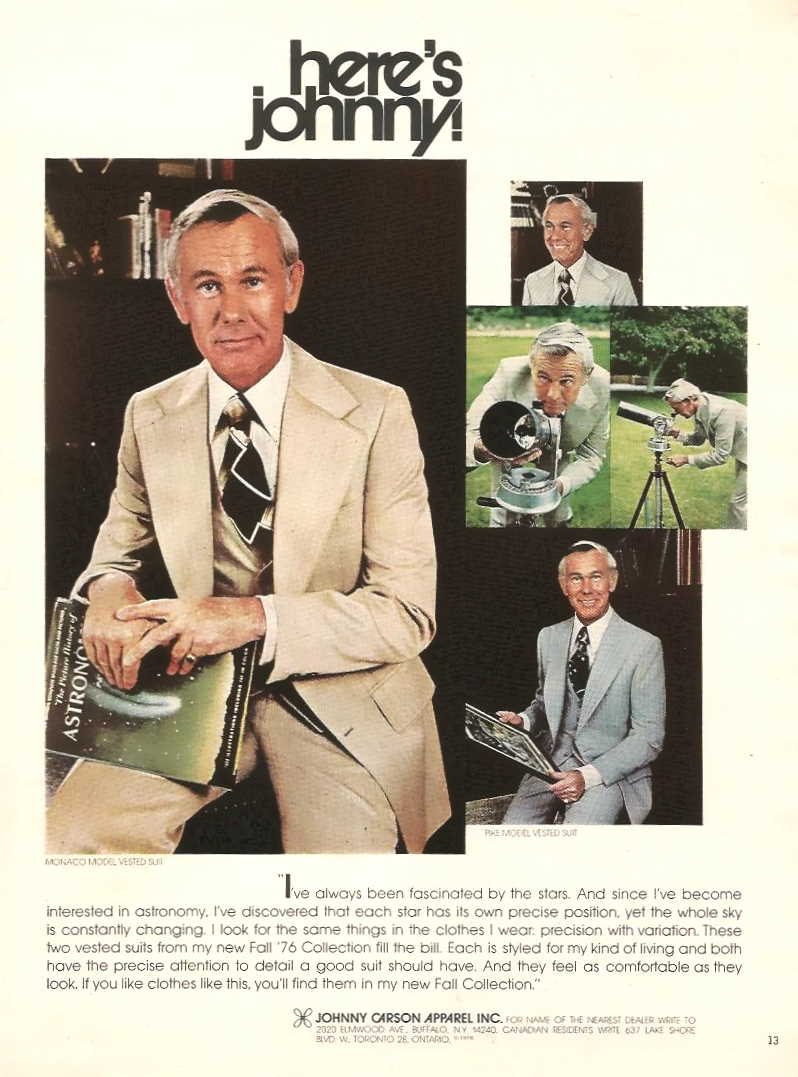

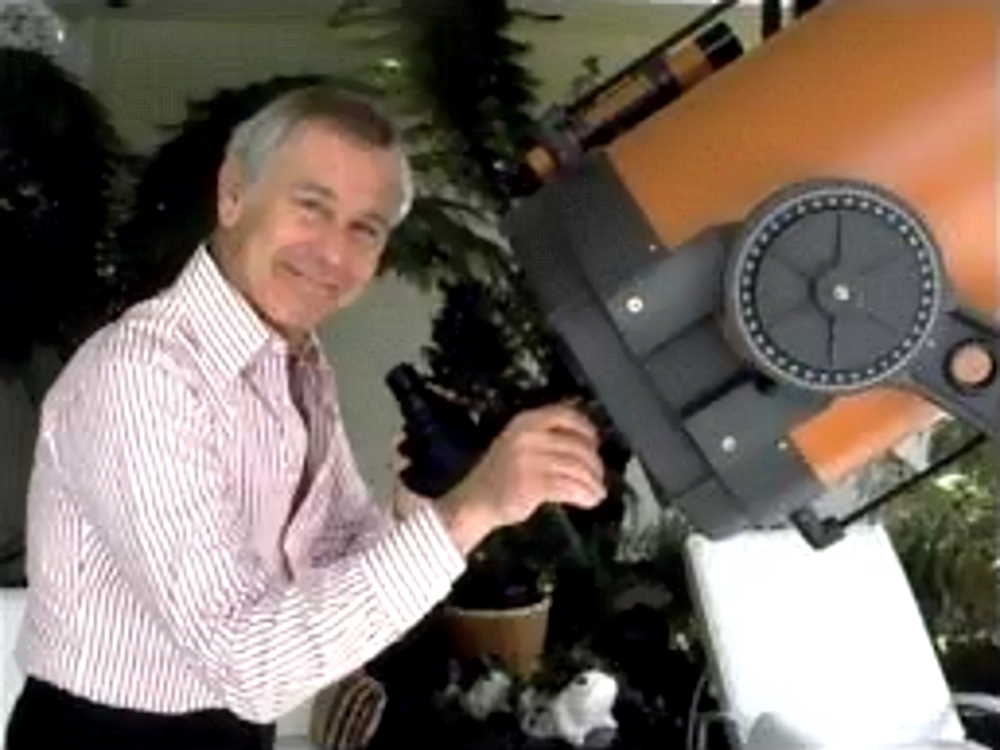

One change to the Questar telescope came from an unlikely source: the celebrated television personality Johnny Carson.

Born in Iowa in 1925, Carson discovered a love for entertaining at an early age. He joined the U.S. Navy in June 1943 and spent two years training as an officer. But while he was en route to the Pacific on a troop ship, the Second World War ended. Back in America, he studied radio, speech, and physics at the University of Nebraska, where he graduated in 1949. Carson hosted a variety of television shows before taking over NBC’s Tonight Show from Jack Paar in October 1962.[1]

While Carson was in New York, he indulged in his love for astronomy, which he picked up during his service in the Navy and which he undoubtedly continued to develop as a student of physics in college. In addition to subscribing to the journal of the Harvard College Observatory, he managed to find time to observe the stars from the roof of his apartment.[2] The year after he began hosting The Tonight Show, he acquired a 60mm Unitron 114 refractor, which he fondly shared with visitors to his home. In June 1967, he acquired a Questar telescope with a quartz primary mirror. It was an ideal instrument for use in an urban setting.[3]

Not long after he bought his Questar, Carson identified a serious flaw in its design, one that had been there since the beginning of Questar’s production in 1954: the lack of a safe way to filter the telescope’s finder system for solar observing.

In the company’s instruction booklet from the late 1950s, Questar unintentionally revealed the nature of the problem: “To find sun use Finder only, with eye a full 2 feet above Eyepiece, not close to it. Look for brilliant exit pupil to appear in eye lens. When it does, switch to filtered high power, and block off Finder Lens with handkerchief or card, to avoid extra light in Control Box.”[4] In later editions of its instruction booklet, Questar continued to use similar language. To say the least, the company offered flawed and dangerous guidance for solar viewing safety, one that no serious observer of the Sun would ever consider to be sufficient.

Carson immediately realized how unsafe Questar’s advice was. Angry, he called Questar’s representative Robert Little, complained about the risk, and demanded that the company do something about it.[5]

Questar responded with little delay. On April 1, 1968, the company began including a solar filter for the finder system with all new units.[6] Questar then turned to introducing the new accessory in its magazine advertising. In the August 1968 issue of Sky and Telescope, Questar described it in greater detail. The hinged filter attached to the finder lens housing on the bottom rear of the telescope above the pick-off finder mirror. “This convenient accessory is intended to protect your eyes when you are trying to locate the sun in the finder system, and it will keep the glare out of the control box when you are using the main system for solar observation. It is a neat little device that can be added to any Questar by sliding it in position and tightening a setscrew. The filter itself is hinged and operates with a tiny knurled knob that moves it into position.” New Questar telescopes shipped with the accessory already installed, and owners of existing instruments could order it for $12.50.[7]

Questar succeeded in keeping one of its celebrity owners happy. Carson continued to use his Questar telescope, and he sometimes brought it onto his television show as a prop for speaking about his hobby.[8]

Johnny Carson continued to host The Tonight Show in New York until he moved it to Burbank in 1972 for easier access to celebrities. One of his frequent guests on the show was his close friend Carl Sagan, with whom he would continue to indulge in his personal interest in astronomy on the air.[9]

Carson would have gladly expanded his roster of likeminded guests if he could have. In a 1979 interview, Rolling Stone writer Timothy White asked him if there was anyone in history whom Carson would like to have on his show. Carson responded:

That’s an interesting question, really. Da Vinci probably; he could’ve been a hell of an interview. Or Isaac Newton, because my hobby is astronomy. I’m fascinated with astronomy. I was up at five the other morning. I woke up—I think the dog was barking—I came outside and got the telescope out and was sitting there at five in the morning. It’s a real mind bender. Gorgeous. Yeah, somebody like Newton, [Kepler], Copernicus.[10]

Carson’s interest in astronomy seeped into his humor, too. The same year of his interview with Rolling Stone, Carson was the emcee of a Friars Club roast for comedian Buddy Hackett. During his remarks, he managed to weave his love for the stars into a good-natured jab at Hackett:

Most of you know I’m an astronomy buff. In fact, I had an observation deck and telescope installed at my home. I use it almost every night, sometimes even to look at the stars. We’re very fortunate to live so close to the Palomar Observatory. They have an amazing telescope there. The glass that formed the lens took seven years to cure, and then the Steuben Company spent another three years polishing it. But it was worth it. You can look through that thing and see back billions of years into space. And I actually visited the Palomar Observatory to look through that famous telescope. And as I looked back into billions of years of history from that device, I could not find a single reason why this goddamn club is giving a dinner for a son of a bitch like Buddy Hackett.[11]

In 1981, astronomers discovered an asteroid and named it 3252 Johnny in honor of Carson. Twenty-three years later, Johnny Carson, who was a heavy smoker, died of emphysema. He was 79 years old.[12]

Carrying Case Updates

In the final years of the 1960s, the company redesigned the carrying case that it included with its Standard and Duplex Questars. Perhaps as part of an emerging commitment to all-American production—or perhaps because its supplier simply decided to end production—Questar discontinued its use of saddle leather cases the company had imported from England since the mid-1950s. Examples of instruments that came with the original cases appeared as late as 1969, when Questar presumably exhausted its stock.[13]

The first indication of the new case emerged in a photograph that appeared Questar’s advertising in the March 1968 issues of Natural History and Scientific American magazines. The image depicted a newly designed case with metal door hinges. The basic form of the case remained the same as the original one, however.[14]

The new design had a minor flaw. The ridge at the top of the case interfered with the removal of the solar filter and eyepiece accessories that were stored in pouches at the top of the case door. In a few years, Questar addressed this problem by introducing slightly modified cases that replaced this top ridge with a flare extending from the top of the case over its door. Questar included cases of this case from around 1970 until around 1982.[15]

Questar’s carrying case supplier during this period was Chic Luggage Company of New York.[16]

The Switch to Questar Brandon Eyepieces

“In the early years,” as Questar comments on its website, “an eyepiece was just an eyepiece.”[17] The oculars that the company first offered with its telescopes were solid performers for their day, but they emerged at a time when observers did not have the overwhelming selection that amateur astronomers enjoy today.

Questar originally included two eyepieces with their telescopes. Both had lenses that David Bushnell imported from Japan on behalf of the company. For low power observing, there was a Koenig ocular with a focal length of 26mm, a 50-degree apparent field of view, and relatively generous eye relief. For higher magnification, Questar included an Erfle eyepiece with a focal length of 13mm, a 75-degree apparent field of view, and eye relief that was on the tighter side.[18] Generally speaking, Erfles are known to suffer from ghost images that are especially obvious during planetary observing. This was precisely one of the main applications that the higher-powered Erfle was intended to serve.

By the early 1970s, an eyepiece was no longer just an eyepiece. While choices were not as rich as they would be for later generations, amateurs had access to somewhat more variety in ocular design than what was available on the market in the mid-1950s.

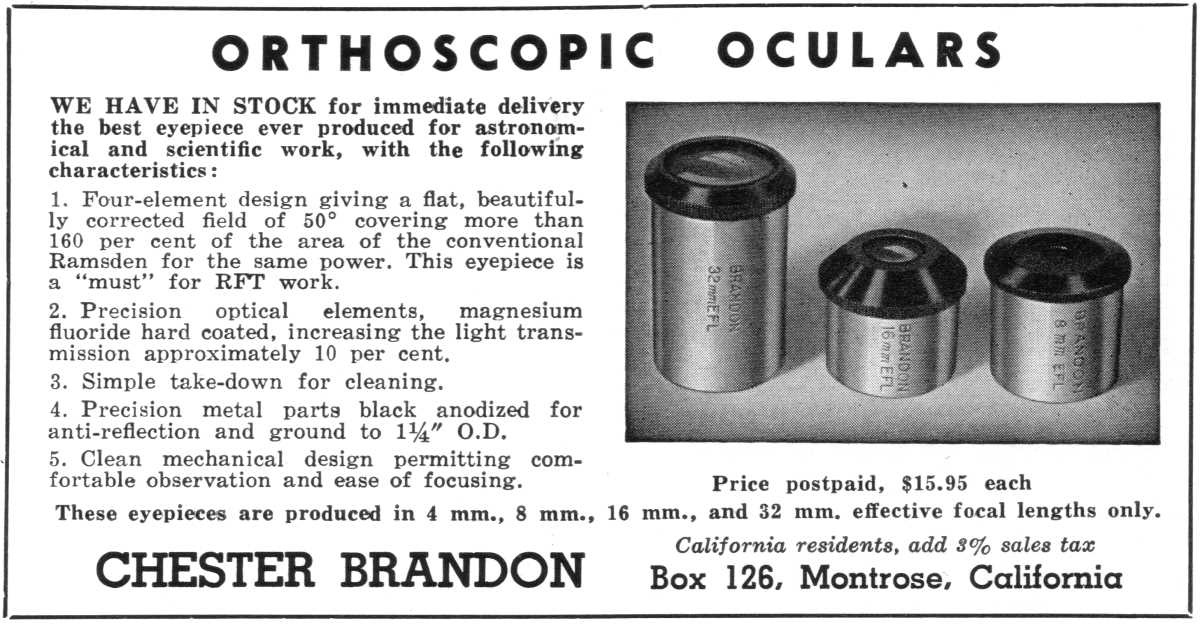

Chester Brandon and the Brandon Eyepiece

The path to improved eyepieces for the Questar telescope began in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1880, Zeiss optician Ernst Abbé designed the orthoscopic eyepiece, which many still regard as the finest choice for planetary observing even today. Its four-element design featured a triplet field lens and a singlet eye lens. This arrangement resulted in less chromatic aberration and ghosting than three-element Kellner eyepieces, which had appeared three decades earlier and which later become the workhorse of amateur astronomers in the middle part of the twentieth century. Another option had emerged in 1860, when Georg Simon Plössl invented an eyepiece design that bears his name. His combination of two nearly identical pairs of lenses was easier to manufacture than orthoscopics, but it also led to tighter eye relief especially in shorter focal lengths. Plössl eyepieces would enjoy a resurgence of popularity toward the end of the twentieth century.[19]

In the 1940s, the American optician Chester Brandon took the orthoscopic design and created his own reversed asymmetric duplet, one that was a derivative of Plössl’s symmetrical design. Sharing a number of characteristics with the Abbé orthoscopic, the Brandon eyepiece offered a 50-degree apparent field of view, high contrast, and no ghosting. They were ideal for planetary observing, although their eye relief, which was generally four-fifths of the eyepiece’s focal length, was on the shorter side.[20]

Don Yeier and Vernonscope

Another individual to emerge on the scene in the 1950s was Don Yeier. His love for astronomy evolved from an intense childhood interest to a profession. Yeier began by working with his father at a tool and die shop to build his own telescopes and mounts. Before long, he was making professional-level instruments. In 1958, he ran his first advertisements in Sky and Telescope. In only a few short years, he had built a stable company.[21]

In 1963, Yeier saw an advertisement in Sky and Telescope that caught his interest: Chester Brandon was interested in selling his business. The two met, and Brandon agreed to sell his concern to Yeier. The younger man then formed Vernonscope and Company, which he named after his son Derrik Vernon, and he added Brandon eyepieces to his product offerings.[22]

Questar’s Decision to Switch

In 1969 or 1970, Rodger Gordon, a friend of Questar, convinced Don Yeier to make the trip down to New Hope and pitch the idea that Brandon eyepieces ought to be included with their telescopes. Yeier and Gordon made their case that one of the best telescopes on the market deserved to be supplied with one of the best eyepieces a person could get. The two were a perfect match.[23]

Five weeks after their meeting, Questar contacted Yeier and placed an order. The two businesses would share a relationship that lasts even today.[24]

Rodger Gordon later pointed out that it was Chester Brandon who helped David Bushnell develop an interest in optics. In this respect, it was ironic that Questar switched away from eyepieces whose Japanese-made lenses were imported by Bushnell and instead adopted eyepieces designed by Brandon.[25]

What drove Questar to make the switch? Did the source for its original eyepieces show signs of drying up? Was the company motivated by a desire to build an all-American product? Or did Questar seek improvements in the performance of the eyepieces it included with its telescopes now that its choices had increased over time?

Early Questar Brandon Eyepieces

Whatever its motivation, Questar transitioned to Brandon eyepieces in the first few years of the 1970s.[26] After it made its commitment to Don Yeier, Questar spent a period of time working through their stock of older eyepieces. The company was also careful to reserve some of its stock for those Questar owners who needed a replacement.[27]

Between 1971 and 1972, Questar adjusted its printed marketing literature to reflect the change. In its 1971 price catalog, where the company indicated that “all Questar components with the exception of eyepieces are made in the United States,” it listed its older 40x and 80x eyepieces for the last time.[28] The next year, the company added its first listing for Brandon eyepieces to its price catalog. Having already moved away from its imported English saddle leather cases, it could now claim without any qualification that “all Questar components are made in the United States.”[29]

The new eyepieces were available in 8, 12, 16, 24, and 32mm focal lengths, provided a range of magnification from 40x to 270x, and were parfocal. Rather than use multicoatings, the Brandon oculars were hard-coated with magnesium fluoride. Their barrels accepted optical glass filters with Vernonscope’s proprietary thread standard. With their distinct curved shape that earned them the nickname “mushroom tops,” their appearance mimicked that of the original Koenig and Erfle eyepieces.[30]

Brandon eyepieces lacked a key feature. The original pair of Questar eyepieces had a built-in diopter for adjusting focus when an observer used them in conjunction with the finder system. When it switched to Brandon eyepieces, Questar needed to introduce a new way to replicate this functionality. The company took the original eyepiece adapter tube, which was simply a brushed aluminum sleeve that was threaded on both sides, and redesigned it. Brandon eyepieces threaded into a new eyepiece adapter which now included the diopter focuser. Rather than adjusting focus for finder mode by working a knurled edge on the eyepiece, the user made adjustments to the adapter.[31]

Years later, Questar introduced enhancements to the design of its diopter eyepiece adapter to accommodate standard 1.25-inch eyepiece barrels. Starting in 1995, the company began tapping two threaded holes into the knurled edge of the adapter top. One could then use a pair of nylon thumbscrews to set typical non-Questar Brandon eyepieces in place. Although the change made the Questar better suited to accept the vast number of standard 1.25-inch eyepieces in existence, only a fraction of them came to focus when an observer used the them with the telescope’s built-in finder system.[32]

In 1971, Vernonscope also offered a set of machined metal storage sleeves whose caps had male threads for accepting the female threads on the bottom of the Brandon eyepieces. After they were discontinued in the late 1970s, Vernonscope made them available again in August 2009.[33]

Questar offered instruments that included the early version of Questar-modified Brandon eyepieces only for a few years. Examples of Questar telescopes built as late as 1974 have appeared on the second-hand market in recent years with this style of ocular.[34]

Modern Questar Brandon Eyepieces

Not long after Questar had switched to Brandon eyepieces, Vernonscope made slight modifications to their appearance as part of an overall update of their line of oculars. Replacing the curved tops of the early versions, the updated Brandon eyepieces featured rubber eyecups that threaded into place. A user could fold the eyecup down, a handy feature for individuals who observed with their eyeglasses on. Early versions of this updated design had their eyecups molded directly onto a metal threaded sleeve while later versions had eyecups that slipped over a plastic threaded sleeve and that could be pulled off. The changes were only cosmetic in nature, however. Vernonscope never altered the optical design of the Brandon eyepiece.[35]

In 2013, Don Yeier retired and sold his company to Tony and Liz Mansfield.[36]

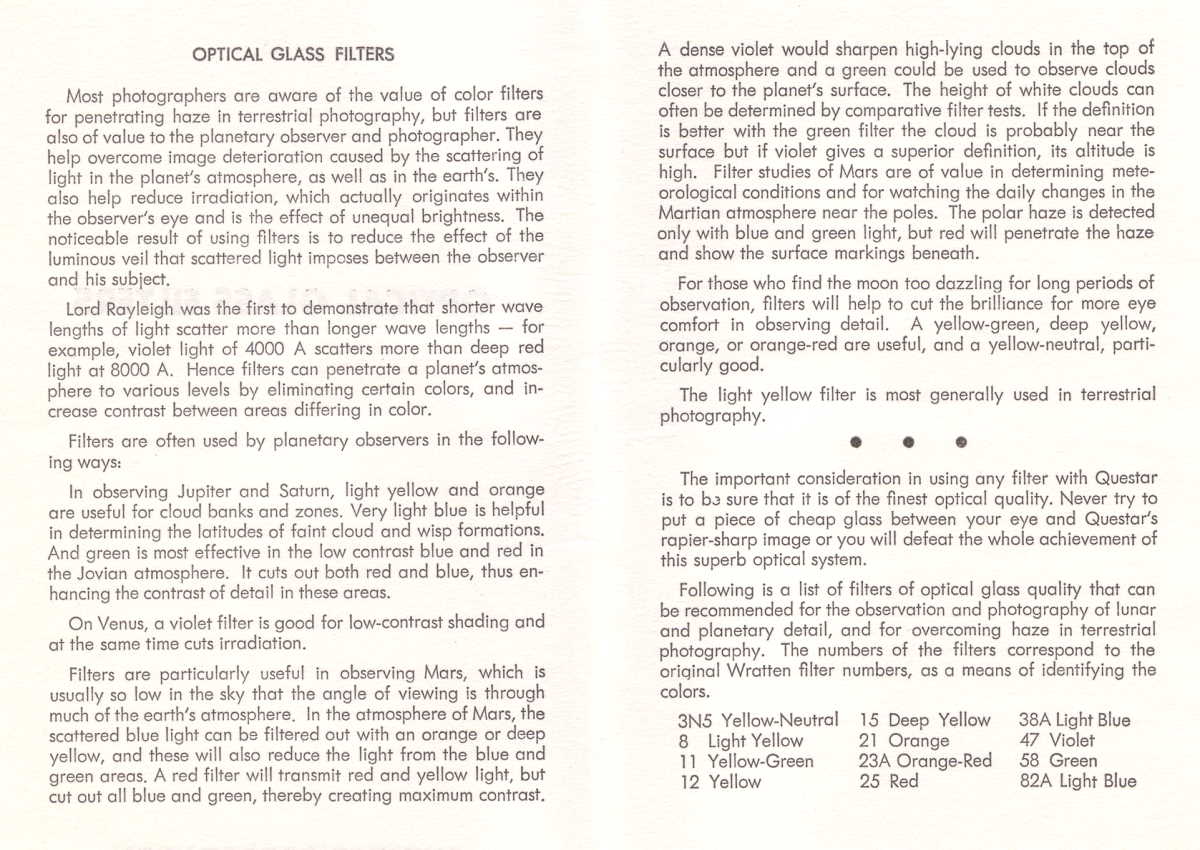

Optical Glass Filters

In its July 1969 price catalog, Questar introduced a set of optical glass filters to its lineup of optical accessories. The company promoted their usefulness for lunar and planetary observing and photography. The company also noted a brief two-page leaflet it had printed on the topic of filtering techniques.[37]

In 1972, Questar also introduced a quick-change filter holder.[38] It featured a small slot in its housing that was useful for swapping out glass or gelatin filters quickly while maintaining the camera’s connection to the telescope’s rear axial port. It extended the focal plane by 19mm, which translated into an effective focal length change of 76mm.[39]

Questar eventully added light pollution reduction filters to their product lineup. In the 1989 Instruments and Accessories catalog, the company described a broadband filter for photo-visual use and a narrowband filter for visual use under heavily light polluted conditions.[40]

Dew Shield and Moon Map Finish Changes

Questar has always operated as an assembly shop that used parts it acquired from its many suppliers. Since the company often had little control over how those suppliers fulfilled the company’s demand, changes to the appearance of many of those parts were inevitable. One such change occurred to Questar’s signature star map dew shield and telescope barrel moon map.

Since Questar began production in the mid-1950s, these navigation aids had been anodized, and their markings were etched and filled with enamel. But the Environmental Protection Agency eventually prohibited the method that Metal Etching Corporation, Questar’s supplier for these parts, had been using to finish dew shields, telescope barrel skins, and other parts.[41]

The regulatory change forced Questar to switch to a dew shield and moon map with screen printed details and a smooth, glossy finish at some point in the 1970s or perhaps even as late as the early 1980s.[42]

New Mounting Options

R. C. Ashley and the Carpod

In the May 1957 issue of Sky and Telescope, the company depicted one clever way that an owner could mount a Questar telescope on a car window. Acting on a suggestion from Dr. Warner Schlesinger of the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, Lawrence Braymer used the plugs that covered the tripod leg holes in the base of the telescope to double their usefulness as a pair of hangers.[43] Questar continued to include this feature with instruments that it built well into the 1980s.[44]

In the early 1970s, the company introduced a new way to mount a Questar onto a car door. This time, another person outside of the company was responsible for suggesting something new. Dr. R.C. Ashley of New York became another friend of the company who made his own contributions to the company’s offerings.

Ashley made his first appearance in Questar’s marketing literature in the company’s 1964 booklet, which contained several instances of his nature photography. The company noted that his Questar was one of the first to receive a wide field conversion in 1963.[45] Questar highlighted his work again in its 1968 booklet. “So as to work without disturbing the birds, Dr. Ashley photographs from inside his car, with his Questar on an improvised shelf.”[46] Later, his commentary on his use of light appeared in the company’s December 1970 advertisement in Sky and Telescope.[47]

In Questar’s 1972 booklet, the company featured even more examples of Ashley’s photography. Perhaps with him in mind, it wrote that “Questar has provoked creativeness and a flare for experimentation in people who have never taken photography seriously before. It has taught people in all disciplines to see more, to see better and to use this prime tool of science for their own purposes.” Questar added that one of Ashley’s “predilections is to photograph from inside his car, where he can sit quietly and wait for a bird to put in an appearance. Then leisurely he focuses and shoots without disturbing his game. For his greater convenience he has developed a window platform to support his Questar.... He says that for a lazy man this beats chasing the birds around in the woods.”[48]

What Questar was describing was the Carpod. A relatively straightforward accessory, it consisted simply of an anodized aluminum alloy plate and an adjustable prop for resting one side of the plate against a car door’s arm rest. The other side of the plate had vinyl-covered hooks to protect the finish of the car door.[49]

The Carpod made its first appearance in Questar’s advertisement in the October 1972 issue of Natural History.[50]

Folding Pier

A more substantial accessory for mounting the far larger Questar Seven also arrived on the scene. After calling it the Questar Portable Pier in the April 1971 issue of Sky and Telescope,[51] Questar later settled on naming it the Folding Pier. No longer was the user of the Questar Seven limited to its tabletop tripod legs or a separate heavy duty camera tripod. The 37-pound Folding Pier featured a rocking cradle that enabled the observer to make adjustments for latitude, and it maintained the center of gravity over the tripod’s center post.[52]

Questar spent the late 1960s and early 1970s working with its many friends to develop new products and refine existing products. Under her leadership, Marguerite Braymer kept the company on its steady course. She continued to follow that theme in Questar’s marketing, too.

Notes

1 “Johnny Carson,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnny_Carson, accessed February 4, 2021.

2 Edward Linn, “The Soft-Sell, Soft-Shell World of Johnny Carson,” Saturday Evening Post, December 22, 1962, https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2016/10/getting-acquainted-johnny-carson/, accessed December 27, 2019.

3 “Questar News and Developments Page,” Company Seven, n.d., http://www.company7.com/questar/news.html, accessed August 12, 2019.

4 Questar Corporation, instruction book, circa late 1950s, 10-11.

5 Michael Edelman, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, June 2, 2016, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/491423-why-did-you-buy-a-questar/?p=7253557, accessed October 13, 2019.

6 Questar Corporation, price catalog, October 1, 1968.

7 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1968, inside front cover.

8 “Questar News and Developments Page,” Company Seven, n.d., http://www.company7.com/questar/news.html, accessed August 12, 2019.

9 “Johnny Carson,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnny_Carson, accessed February 4, 2021.

10 Timothy White, “Johnny Carson: The Rolling Stone Interview,” Rolling Stone, March 27, 1979, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/johnny-carson-the-rolling-stone-interview-45826/, accessed December 27, 2019.

11 Henry Bushkin, Johnny Carson (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013), 69.

12 “Questar News and Developments Page,” Company Seven, n.d., http://www.company7.com/questar/news.html, accessed August 12, 2019; “3252 Johnny (1981 EM4),” NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, n.d., https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?orb=1;sstr=3252, accessed February 5, 2021.

13 As of May 5, 2021, the latest Questar known to the author to have included the original English saddle leather carrying case is #9-CV-DP-4008-BB, built in 1969 (“Q_Inventory_083115b.xls” (unpublished manuscript, August 31, 2015), spreadsheet, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/Questar%20Information%20Database/, accessed October 15, 2019).

14 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, March 1968, 10; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, March 1968, 134.

15 As of February 4, 2021, the latest example known to the author to include the initial redesign of Questar’s leather carrying case that appeared in the late 1960s is #0-CV-4350-BB, built in 1970 (“Questar,” Astromart, November 14, 2008, https://astromart.com/classifieds/astromart-classifieds/telescope-catadioptric/show/questar-now-sold-thank-you-all-very-much, accessed February 4, 2021). The latest example known to the author to include the redesigned case that appeared in the early 1970s is #2-DP-Z-8498-BB, built in 1982 (“Questar Duplex, Zerodur, Broadband,” Astromart, February 2, 2010, https://astromart.com/classifieds/astromart-classifieds/telescope-catadioptric/show/questar-duplex-zerodur-broadband-pending-david, accessed February 4, 2021).

16 Jim Perkins, email message to author, September 4, 2020.

17 Questar Corporation, “Eyepieces Used by Questar,” n.d., https://www.questarcorporation.com/eyepiece.htm, accessed February 1, 2021.

18 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, February 1957, 186; “Early Production Questar 3-½ Telescopes: 1954 and 1955,” Company Seven, n.d., http://www.company7.com/library/questar/que54-55.html, accessed November 3, 2019.

19 Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer, The Backyard Astronomer’s Guide (Richmond Hill, Ontario: Firefly, 2008), 70; “Choosing the Correct Eyepiece,” Edmund Optics, n.d., https://www.edmundoptics.com/knowledge-center/application-notes/microscopy/choosing-the-correct-eyepiece/, accessed May 5, 2022; Bruce MacEvoy, “Astronomical Optics,” handprint.com, November 26, 2013, https://www.handprint.com/ASTRO/ae5.html, accessed May 5, 2022.

20 Chris Lord, “Evolution of the Astronomical Eyepiece” (unpublished manuscript, n.d.), typescript, 6, 37, https://www.brayebrookobservatory.org/BrayObsWebSite/BOOKS/EVOLUTIONofEYEPIECES.pdf, accessed February 2, 2021.

21 Bill Swan, “A Sharp Eye for Business: Yeier Builds a Precision Optics Empire,” Ithaca Times, November 3, 2010, https://www.ithaca.com/news/local_news/a-sharp-eye-for-business/article_db43dc3a-0d4f-5ea8-aaa1-5ed6c50a2a4d.html, accessed October 7, 2020.

22 Bill Swan, “A Sharp Eye for Business: Yeier Builds a Precision Optics Empire,” Ithaca Times, November 3, 2010, https://www.ithaca.com/news/local_news/a-sharp-eye-for-business/article_db43dc3a-0d4f-5ea8-aaa1-5ed6c50a2a4d.html, accessed October 7, 2020.

23 Rodger Gordon in discussion with the author, August 15 and October 7, 2020; Bill Swan, “A Sharp Eye for Business: Yeier Builds a Precision Optics Empire,” Ithaca Times, November 3, 2010, https://www.ithaca.com/news/local_news/a-sharp-eye-for-business/article_db43dc3a-0d4f-5ea8-aaa1-5ed6c50a2a4d.html, accessed October 7, 2020.

24 Bill Swan, “A Sharp Eye for Business: Yeier Builds a Precision Optics Empire,” Ithaca Times, November 3, 2010, https://www.ithaca.com/news/local_news/a-sharp-eye-for-business/article_db43dc3a-0d4f-5ea8-aaa1-5ed6c50a2a4d.html, accessed October 7, 2020.

25 Rodger Gordon in discussion with the author, August 15, 2020.

26 As of October 25, 2021, the last Questar known to the author to have the original Questar eyepieces with Japanese-made lenses is #2-CV-DP-5214-BB-AC, built in 1972 (MerylB, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, July 5, 2019, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/667426-questar-telescope/, accessed June 3, 2022).

27 Rodger Gordon in discussion with the author, August 15 and October 7, 2020.

28 Questar Corporation, price catalog, 1971.

29 Questar Corporation, price catalog, 1972. As of February 3, 2021, the earliest Questar known to the author to have the early Questar Brandon eyepieces is #2-DP-5304-BB, built in 1972 (“Questar Duplex ++,” Astromart, August 4, 2017, https://astromart.com/classifieds/astromart-classifieds/telescope-catadioptric/show/questar-duplex-413969, accessed February 3, 2021).

30 Questar Corporation, “Questar-Modified Brandon Orthoscopic Oculars,” n.d.; Vernonscope, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, September 1974, 194; Questar Corporation, “Eyepieces Used by Questar,” n.d., http://www.questarcorporation.com/eyepiece.htm, accessed July 3, 2019

31 Questar Corporation, “Eyepieces Used by Questar,” n.d., http://www.questarcorporation.com/eyepiece.htm, accessed July 3, 2019.

32 Questar Corporation, “Eyepieces Used by Questar,” n.d., http://www.questarcorporation.com/eyepiece.htm, accessed July 3, 2019.

33 “Questar Vernonscope Eyepiece Canisters / Metal Protective Tubes of 1971,” Company Seven, n.d., http://www.company7.com/library/questar/q1971canisters.html, accessed February 3, 2021; “Questar Eyepiece Canisters / Metal Protective Tubes,” Company Seven, n.d., http://www.company7.com/questar/products/questcanisters.html, accessed February 3, 2021.

34 As of June 30 ,2023, the last Questar known to the author to have the early Questar Brandon eyepieces is #4-DP-5781, built in 1974 (“Questar Duplex With Full Aperture Solar Filter,” Astromart, February 15, 2018, https://astromart.com/classifieds/astromart-classifieds/telescope-catadioptric/show/questar-duplex-with-full-aperture-solar-filter, accessed June 30 ,2023).

35 Questar Corporation, “Eyepieces Used by Questar,” n.d., http://www.questarcorporation.com/eyepiece.htm, accessed July 3, 2019.

36 “About,” Vernonscope, n.d., http://www.vernonscope.com/, accessed October 7, 2020.

37 Questar Corporation, price catalog, July 1, 1969.

38 Questar Corporation, price catalog, 1972.

39 Questar Corporation, “Instruction Book II: Questar and the Camera,” 1976.

40 Questar Corporation, Instruments and Accessories catalog, 1989.

41 Alt-Telescopes-Questar Majordomo list message, July 28, 1999, digest 398, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/Alt-Telescopes-Questar%20Digests/, accessed October 14, 2019.

42 Determining the exact timing of Questar’s move away from etched and enamel filled star map dew shields and moon map barrel skins represents a challenging undertaking. Company Seven indicated that the older manufacturing technique “would be discontinued by the late 1960’s when the charts became silk screened” (“Early Production Questar 3-½ Telescopes: 1954 and 1955,” Company Seven, n.d., http://www.company7.com/library/questar/que54-55.html, accessed July 5, 2019). Yet this estimated transition timeframe is likely too early, as several examples from the 1970s feature dew shields with etched and enamel-filled markings. A consideration of various Standard Questar examples does not clarify matters. On one hand, the emergence of silk-screened dew shield markings perhaps appeared in the early 1970s. As Cloudy Nights user “Darkskyaz” reported in May 2020, Jim Perkins revealed that the change to screen printed dew shields occurred in 1972 due to environmental regulations (Darkskyaz, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, May 30, 2020, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/580599-questar-design-change-history/?p=10227611, accessed February 10, 2021). In July 2020, the author also observed a 1972 Questar that featured a dew shield that was not etched and enamel filled. But this example could have been the recipient of a later retrofit. On the other one hand, Questar may have included etched and enamel filled dew shields with Standard Questars well into the 1970s and perhaps beyond. In April 2021, Cloudy Nights user “Opie Taylor” reported that a 1971 Questar in his possession has an etched and enamel filled dew shield (Opie Taylor, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, April 20, 2021, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/580599-questar-design-change-history/?p=11047499, accessed April 21, 2021). And in December 2021, Joe Bergeron also reported his 1976 Questar had the same marking type (Joe Bergeron, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, December 14, 2021, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/794835-questar-history/?p=11565136, accessed December 14, 2021). Etched and enamel filled dew shields may have persisted into the 1980s. Ralph Foss generally noted a discussion thread on Cloudy Nights where collectors identified 1982 as the year that Questar made the change (Ralph Foss, “Questar Timeline” (unpublished manuscript, September 22, 2007, revised September 19, 2009), typescript).

43 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, May 1957, 358.

44 Ben Langlotz, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, June 12, 2017, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/580599-questar-design-change-history/?p=7935420, accessed July 11, 2019.

45 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, July 1964, 18-19.

46 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1968, 12-13.

47 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, December 1970, inside front cover.

48 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1972, 9, 23.

49 Questar Corporation, “Carpod,” n.d.

50 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, October 1972, 109.

51 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1971, inside front cover.

52 Questar Corporation, price catalog, 1971.