§ 4.1. New Offerings for Photographers and Cinematographers

On This Page

When Lawrence Braymer commented on telescopic photography in the early 1960s, he addressed a number of problems. Poor seeing, vibration caused by the mechanics of the mirror and shutter, achieving sharp focus, and determining correct exposure times were all challenges. Braymer advised that the photographer should avoid taking pictures during the heat of day, and he suggested that one should experiment to find the best conditions for one’s location. Vibration was best addressed by choosing a camera body with the smoothest shutter action. Questar offered modified versions of a number of camera bodies with features that further limited vibration. Upon working the telescope’s focuser, one could achieve the sharpest negative by using a regular ground glass screen with a clear central spot. And as far as exposure times were concerned, one was best served simply by shooting lots of pictures.[1]

Braymer directed much of his commentary toward problems the terrestrial photographer faced. Whatever astronomical targets that most attempted to capture on film were limited to the brightest objects in the sky: the Moon, the Sun, and the planets. Those were the images that most frequently appeared in Questar marketing literature and advertising.

As it was built, the Questar telescope was particularly well suited to those tasks. Its electric drive motor had sufficient accuracy to enable the photographer to capture excellent images of bright objects. One could render them on film by using relatively quick exposure times.

But other problems remained unresolved. The Questar telescope did not offer the ability to fine-tune the tracking rate of its electric motor. One was also tied to being close to a household electrical wall outlet for power. And making adjustments during long exposures was difficult at best.

Paging through issues of Sky and Telescope from the latter half of the 1960s and the first half of the 1970s, one quickly sees that amateur astronomers had yet to push the boundaries of what was truly possible in astrophotography.

In addition to its coverage of the excitement surrounding the Apollo program and other space missions of the era, Sky and Telescope featured the construction and applications of large professional observatories. Manufacturers who supplied them with their instrumentation highlighted their behemoths in advertisements. Boller & Chivens was one such company. They regularly featured instruments that dwarfed those standing next to them. Whatever photographic equipment the company sold was most often limited to use with professional-grade telescopes or was intended for specialized applications like spectrographic analysis.

For the amateur, visual observing continued to dominate the pages of Sky and Telescope. Manufacturers offered mostly long-tube reflectors and refractors on equatorial mounts, although catadioptric telescopes other than the Questar began making their appearance.

Meaningful deep-space astrophotography was still mostly out of reach for the average amateur in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Whatever images of nebulae and star clusters that appeared in Sky and Telescope were most often taken either by large telescopes at professional observatories or by amateurs who were unusually talented with using film cameras that were attached to reflectors with generous aperture.

For everyone else, manufacturers sold what many today would see as crude and cumbersome accessories for astrophotography. Sellers like Edmund Scientific offered brackets for holding a typical 35mm film camera over an eyepiece. Such contraptions were mostly useful for imaging bright objects like the Moon. Unitron featured more sophisticated accessories for their classic long-tube and equatorially-mounted refractors. One such product was the company’s Astro-Camera 220, which consumed single 3 1/4" x 4 1/4" plates of film. But for the most part, one rarely saw telescopes that were well suited for astrophotography in Sky and Telescope.

The Questar was one exception. Photography had always been a central design feature of the company’s signature telescope since day one. Other photographically-minded variations of this core product appeared not long after production began in 1954.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Questar introduced a flurry of accessories for photographers and cinematographers. Friends of the company played a key role in designing new products that enhanced the photographer’s ability to target deep-space objects with surprisingly good results. To its credit, Questar demonstrated a notable level of receptiveness as it took the ideas of its friends and made them into products that the company produced, marketed, and profited from.

Robert Little’s Innovations

One man closely associated with Questar was Robert Little, who was an advertising salesperson living in Los Angeles when C.L. Stong featured his astrophotography work in the December 1965 issue of Scientific American. Little was not yet thirty years old when he acquired a ten-inch reflecting telescope around 1960. In time, he grew tired of visual observing and tried photography, but he soon discovered how vibration and the shaking of his telescope in the breeze made sharp exposures impossible. “Such problems disappeared,” he wrote, “when I acquired my Questar.” With its built-in electric motor and “a variable-frequency oscillator” of his own design and construction, he was able to keep the telescope “locked onto a desired star by changing the frequency of the oscillator.” Little also improvised brackets for attaching his 35mm camera and a 50 or 500mm lens to his Questar, which “served merely to keep the lenses trained on the stars during exposure intervals that ranged from 10 to 45 minutes.” For added functionality, Little fashioned an eyepiece with illuminated crosshairs. “The beauty of the equipment is in its compactness, solidity and ease of transportation and use.” Wind became something of a non-concern, and he was able to work from a comfortable seated position. Stong’s article went on to describe Little’s technique in more detail, and he included a sampling of photographs that proved how well it worked.[2]

Robert Little’s inventions served as the inspiration for several accessories that Questar came to offer by the end of the 1960s.

Piggy-back Mount

In its 1960 booklet, Questar offered a preview of what was possible by including a wide-field image of the night sky that had been made with a camera mounted on one of its telescopes. “Starfields are best photographed by the fast Schmidt wide-field cameras. Our own little cameras are miniature Schmidts in speed and field, so Questar owners have mounted them piggy-back on the electrically driven ‘scope and secured several thousand star images in only 4 minutes.”[3]

After making its early suggestion, the company waited years to introduce an accessory that enabled the photographer to mount a camera on top of a Questar for wide-field imaging. In the August 1968 issue of Sky and Telescope, the company described “the Piggy-back Mount, which supports your 35-mm. camera on Questar’s barrel so that you can take pictures of deep-sky objects while utilizing Questar’s superb drive for following.” The company went on to credit Robert Little, who used a similar apparatus of his own design to capture superb wide-field images of the stary night sky. The accessory that Questar sold was made of black anodized 2024-T4 aluminum and was priced at $60.[4]

Varitrac

Another problem that Robert Little addressed was two-fold: achieving precise control of the rate that the Questar’s electric motor tracked with the apparent motion of the sky and freeing oneself from having to depend upon a nearby electrical outlet for power.

In 1959, Questar had already offered a drive inverter that worked off of typical car batteries available to its customers. It was made by American Television and Radio Company of St. Paul, Minnesota.[5] But the company offered no other details, and the product did not appear in its promotional literature thereafter.

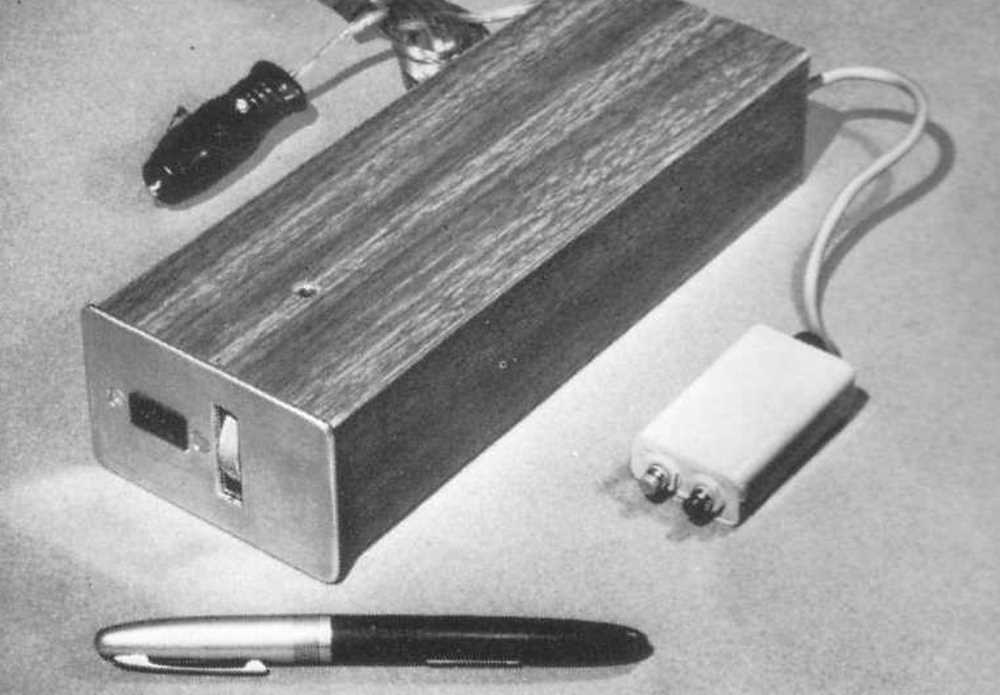

In its 1964 price catalog, Questar introduced the Varitrac, “a high quality power source for the astronomer that frees him from house current.” It operated from any 12-volt DC power source without the need for an inverter or vibrator, and it included a 20-foot power cord that plugged into an automobile’s cigarette lighter receptacle. It also featured a hand-held controller with two buttons for speeding or slowing the tracking rate from 56 to 64 cycles per second. One could switch from sidereal to lunar time and achieve far more precise following of the Moon for photography. Its price was $129.50.[6]

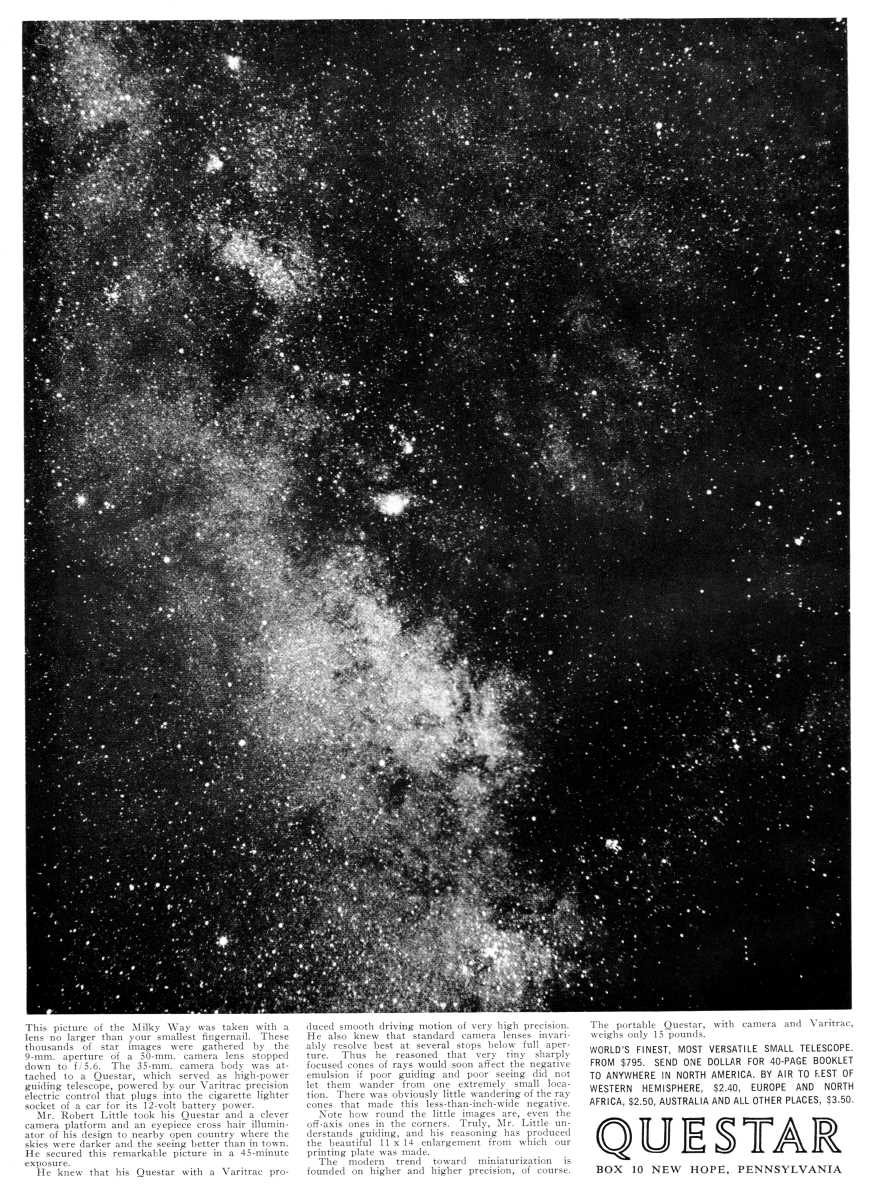

In its advertisement appearing in the September 1965 issue of Sky and Telescope, Questar acknowledged Robert Little for inspiring the Varitrac. Under a reproduction of a 45-minute wide-field exposure of the Milky Way that Little had captured with a 50mm lens and a 35mm camera riding piggyback on his Questar, the company described his use of a Varitrac controller under dark country skies. Little “knew that standard camera lenses invariably resolve best at several stops below full aperture. Thus he reasoned that very tiny sharply focused cones of rays would soon affect the negative emulsion if poor guiding and poor seeing did not let them wander from one extremely small location. There was obviously little wandering of the ray cones that made this less-than-inch-wide negative.” Without doubt, “Mr. Little understands guiding, and his reasoning has produced the beautiful 11 x 14 enlargement from which our printing plate was made.”[7]

Questar introduced an updated Varitrac II controller in its April 1966 price catalog. While its appearance was quite different from the original, its functionality was essentially the same.[8] In April 1970, the company offered an AC to DC converter which allowed owners of the original Varitrac to operate their units from a household outlet or from a battery.[9]

In much the same way that the company used outside suppliers to produce many of its products, Questar continued this practice by working with Wolfson Electronics of Venice, California, to manufacture the Varitrac II.[10]

Little’s Work by the End of the 1960s

By the late 1960s, Robert Little enjoyed a close relationship with Questar. The company included several examples of his work in its 1968 booklet. Featuring a full spread of wide-field astrophotography in addition to several images of Anna’s hummingbirds in flight, Questar described his equipment and technique in greater detail, and it pointed out in particular that perfect guiding is essential for starfield photographs.[11]

Questar also continued to feature Little’s wide-field photography in its magazine advertising. “There are so many ways you can use a Questar,” the company trumpeted in the February 1969 issue of Sky and Telescope. Little’s photograph of the Great Orion Nebula “demonstrates how effectively deep-sky objects can be photographed in color with a 35-mm. camera, when you have an accurate guiding system.” Questar boasted that Little’s photography was on display in the Hayden Planetarium in New York.[12]

While available evidence does not clearly indicate whether he was a direct employee of the company, Questar held him in high enough regard to consider him as one of its representatives. Working in that capacity, for instance, he drove up to Toronto in early 1969 to demonstrate the new Questar Seven in front of members of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada.[13]

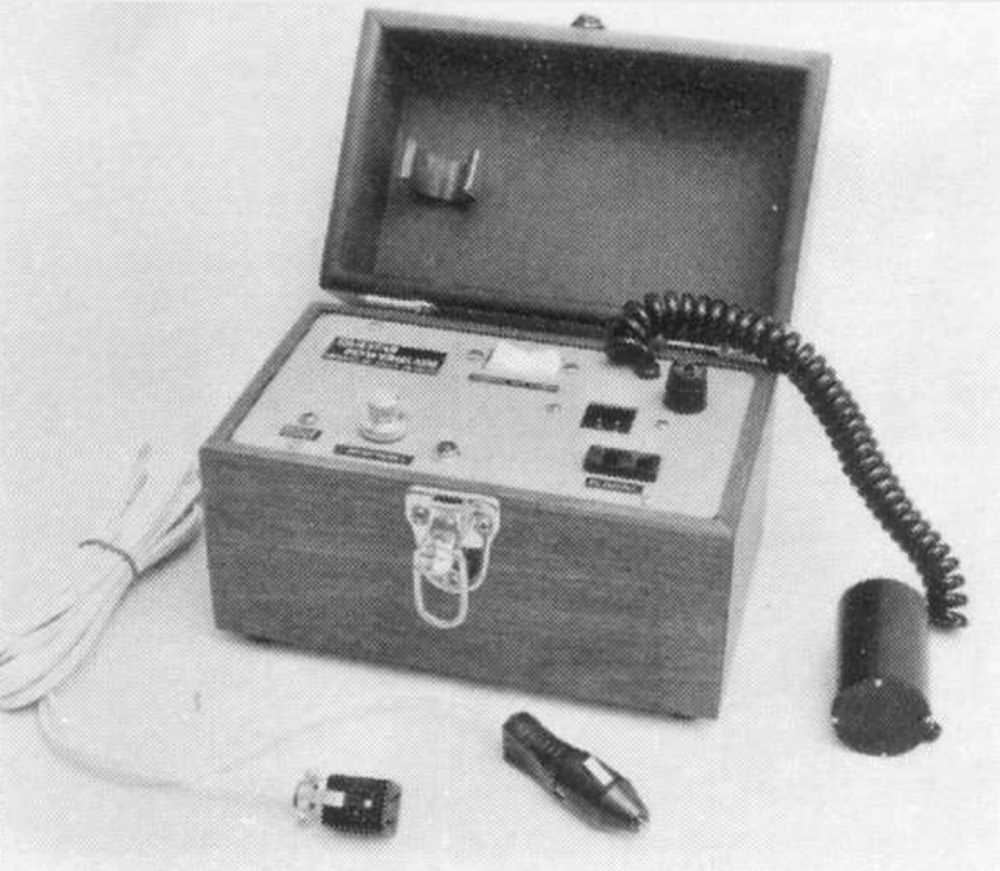

Powerguide

By 1970, Robert Little was not finished devising innovations to improve the experience of photographers who used a Questar telescope. In April of that year, Questar introduced what may be his most recognized contribution, the Powerguide controller. As the replacement for the Varitrac and Varitrac II, the Powerguide could operate using either an AC wall outlet or from a 12-volt DC power source. It featured a switch for selecting sidereal or lunar tracking rates. A twelve-foot power cord plugged into either an auto cigarette lighter or 110-volt household outlet. Its output was five watts, and it drew one ampere. Its handheld control allowed one to stop the drive or speed it up beyond sidereal rate.[14]

The initial version of the Powerguide proved to be a long-running success. Modifying it only slightly over the years, Questar produced this accessory until the late 1980s.[15] The company maintained its use of the name when it substantially redesigned the product in subsequent years.

Illuminated Crosshair Reticle Eyepiece

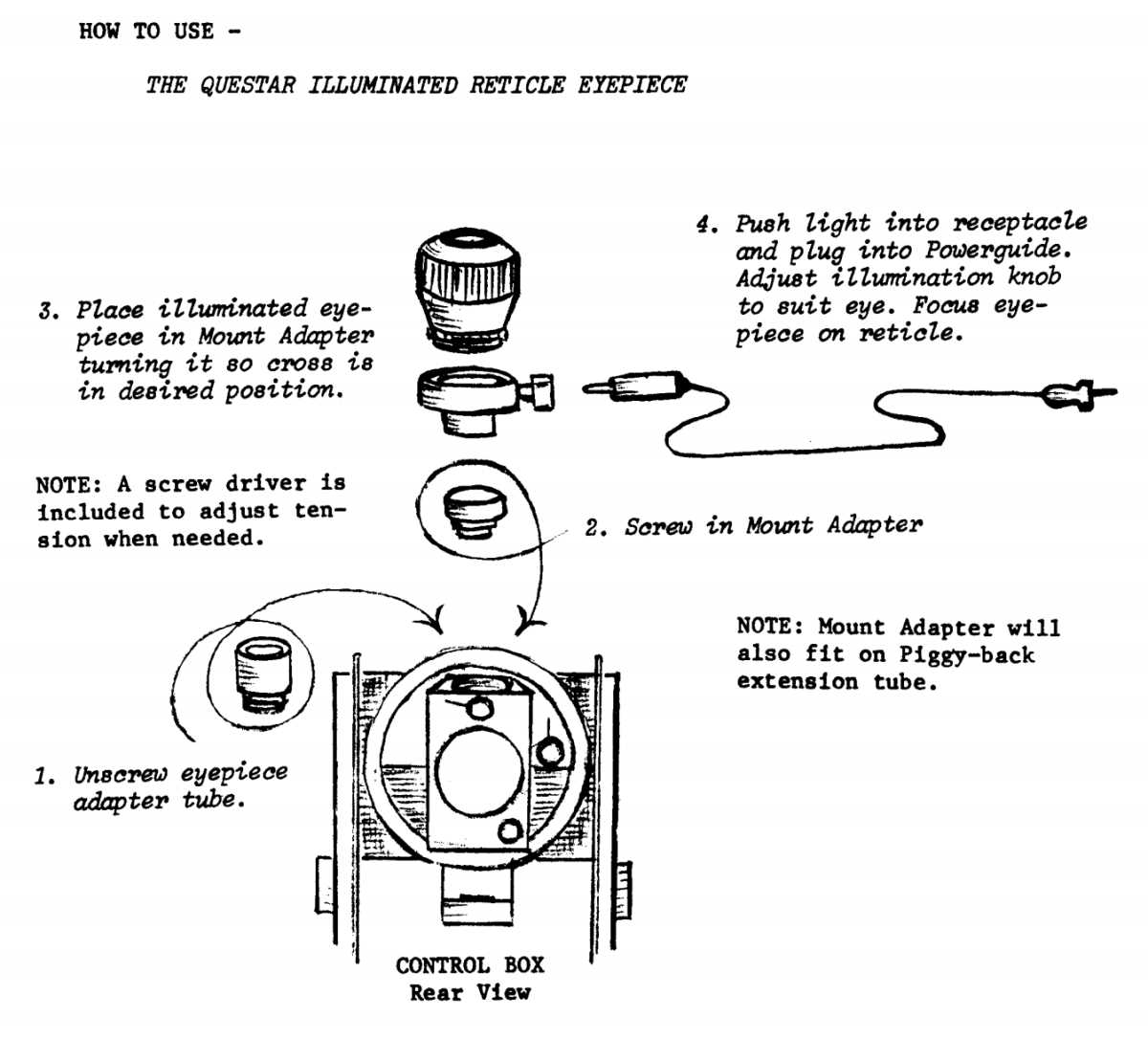

Another key accessory that Robert Little developed was the illuminated crosshair reticle eyepiece. Drawing its power from the Powerguide, it enabled the photographer to target a guide star in its field of view and enable minute tracking corrections in a way that was far easier than what a plain eyepiece could provide. Questar introduced this accessory at the same that it announced the Powerguide in April 1970.[16]

The same month, the company advertised a reticle control allowing Varitrac and Varitrac II owners to use the illuminated crosshair reticle eyepiece on either AC or DC current. Questar also recognized Robert Little’s role in developing that additional accessory, the Powerguide, and the illuminated crosshair reticle eyepiece .[17]

Little’s Career After the Mid-1970s

Always an entrepreneur, Robert Little went on to start his own business as a reseller of astronomy and photography equipment. At the bottom of a full-page advertisement he ran in the November 1976 issue of Sky and Telescope, Little characterized himself as the former field representative for Questar, a regional sales manager for Celestron, and the photographic director for Eclipse Cruises, Inc. In addition to operating his own business, he also worked as a sales manager for Criterion Manufacturing Company.[18]

Robert Little died at his home in Brooklyn in December 2010 at the age of 77. In his remembrance that appeared in the January 2011 issue of Eyepiece: Journal of the Amateur Astronomers Association of New York, Dan Harrison wrote that Robert Little’s professional work brought him into contact with Scientific American, Questar, Celestron, and Bausch and Lomb. He was an accomplished astrophotographer whose 1986 book Astrophotography: A Step-by-Step Approach drew wide acclaim. As an active member of the Amateur Astronomers Association of New York, he led observing sessions and taught classes on astrophotography at the Hayden Planetarium. Little also pioneered the practice of observing solar eclipses from ships at sea, and one of his photographs of a solar eclipse appeared on the cover of Life magazine.[19]

Hubert Entrop and the Starguide

A tinkerer, a self-taught engineer, an intense competitor, and an individual whose wide range of interests included aviation, speedboats, astronomy, and photography, Hubert Entrop established a friendship with the company. In a way, he was another typically extraordinary Questar owner.

Entrop’s Early Years

Hubert Entrop was born on August 7, 1923, and grew up in the South Park neighborhood of Seattle near Boeing Field. During his boyhood, he was captivated by taking all manner of things apart and putting them back together again. He was particularly drawn to studying airplane and boat designs, two interests that were well suited to his close proximity both to the aerospace industry and to the water in Seattle. Passing up a college education, Entrop chose instead to become a self-taught engineer. Later in life, as Seattle Times journalist J. Patrick Coolican wrote, his work “contributed to a range of engineering advances—ensuring the safety of commercial airplanes, propelling boats to go record speeds, building telescopes for clearer views of the universe.”[20]

After serving in the U.S. Army in Australia during World War II, Entrop moved to Ballard, Washington, to work for Boeing. There, he collaborated with Herm Dittmer and Howard Louth to uncover aircraft design flaws using the company’s wind tunnel. Entrop and Dittmer’s particular work involved building airplane models. “Their abilities to design and do superfine machine shop work was outstanding,” as Seattle Astronomical Society member Alan Macfarlane remembered.[21]

Not long after landing his job at Boeing, Entrop took up outboard speedboat racing in 1951.[22] His abilities grew as fast as he could drive his hydroplanes across the water. With numerous reporters watching on June 7, 1958, the American Power Boat Association timed a new world outboard speed record as Entrop ran his RX-3 at an average two-way speed of 107.821 mph. At the age of twenty-four, he became the first American to go faster than 100 miles per hour in an outboard-driven boat.[23]

Entrop soon stacked up more honors. In 1958, he became a member of the Gulf Oil Corporation’s “100 Mile Per Hour Club” with his class F outboard hydroplane named “R-22.” Membership in the club was limited to those who had driven a powerboat 100 miles per hour or faster in American Power Boat Association-sanctioned regattas on courses approved for such records.[24] The next year, Sports Illustrated reported that Entrop was the 1959 National Motorboat Class champion in the Class F Outboard Hydroplane category.[25] In 1960, Entrop broke yet another record by running an outboard motor speedboat at 122.979 miles per hour.[26]

Years later, Jack Leek, a fellow hydroplane racer who competed against Entrop before forming a team with him, commented that he was a perfectionist with everything he touched. “He did everything right,” Leek said. Entrop pushed the bounds of hydroplane engineering. He developed a craft whose tail rose out of the water and reduced friction as a result. But not long after his record-breaking runs, he quit racing. “Winning the races was secondary to proving various ideas he had,” Leek said.[27]

Although he left speedboat racing, the competitive spirit did not leave Entrop. In the early 1960s, he again took up his childhood interest in model airplanes, this time with a competitive edge. Eventually, he built a free-flight model with a wingspan of 29 feet, the world’s largest. Just as he had done in hydroplane racing, Entrop bested his rivals in model airplanes. “He beat the pants off everybody,” Jack Leek said.[28]

At roughly the same time that he left hydroplane racing and began competing with model airplanes, Entrop and his professional colleague Herm Dittmer also developed an interest in optics, astronomy, and photography. While his friend was more drawn to building his own telescopes, Entrop discovered the Questar telescope.[29] He bought his first one in 1965.[30] It was a natural match for his perfectionism.

In a profile that appeared in the Seattle Astronomical Society’s October 2002 newsletter, Alan Macfarlane recounted Entrop’s early progress:

Because of the superb optics and construction of the Questar, Hugh decided to put it through several fascinating tests. He set up his scope in Alki and started taking pictures of his brother in his office on [Second Avenue in Seattle]. Then from the same spot, he and Herm photographed license plates of cars parked on Western Avenue.[31]

The results were so good that Questar presented Entrop’s photographs of the Seattle shoreline in the company’s 1968 and 1972 booklets. Demonstrating how the user could increase magnification without losing detail, the series included two perspective images Entrop made using a 55mm and 600mm lens. He used his Questar to take the other photographs. He increased magnification with an increasingly aggressive combination of extension tubes and Barlow lenses. In its reproduction of the images, Questar included the film sprocket holes to demonstrate the size and resolution of the negative.[32]

At the same time, Entrop began his work imaging deep space objects, planets, comets, and the Sun. “Here was a dedicated astrophotographer who was taking an f/19 3 1/2-inch telescope and turning out results that rivaled Mt. Wilson!” Macfarlane wrote.[33]

Starguide

In a form that was true to his love for tinkering, Entrop was not content to use his Questar just as he received it from the company. As his skills in astrophotography improved, he encountered the same problem that others faced. While attempting to take lengthy exposures over several minutes, he discovered the need for continuous and accurate guiding.

In an undated leaflet on deep-sky photography, Questar described the problem in greater detail, and the company hinted that a solution was in the works. The problem of guiding was two-fold:

First, there is really no such thing as a perfect star drive. Even the most carefully made tracking mechanism has residual machining tolerances which result in a certain amount of periodic error. (The drive moves slightly faster and slower in regular fashion.) Second, atmospheric refraction affects the position, and therefore the pace, of any celestial object according to its zenith distance. Consequently, even the 200-inch Hale giant will photograph stars as streaks, unless it is guided and corrected constantly by the observer.[34]

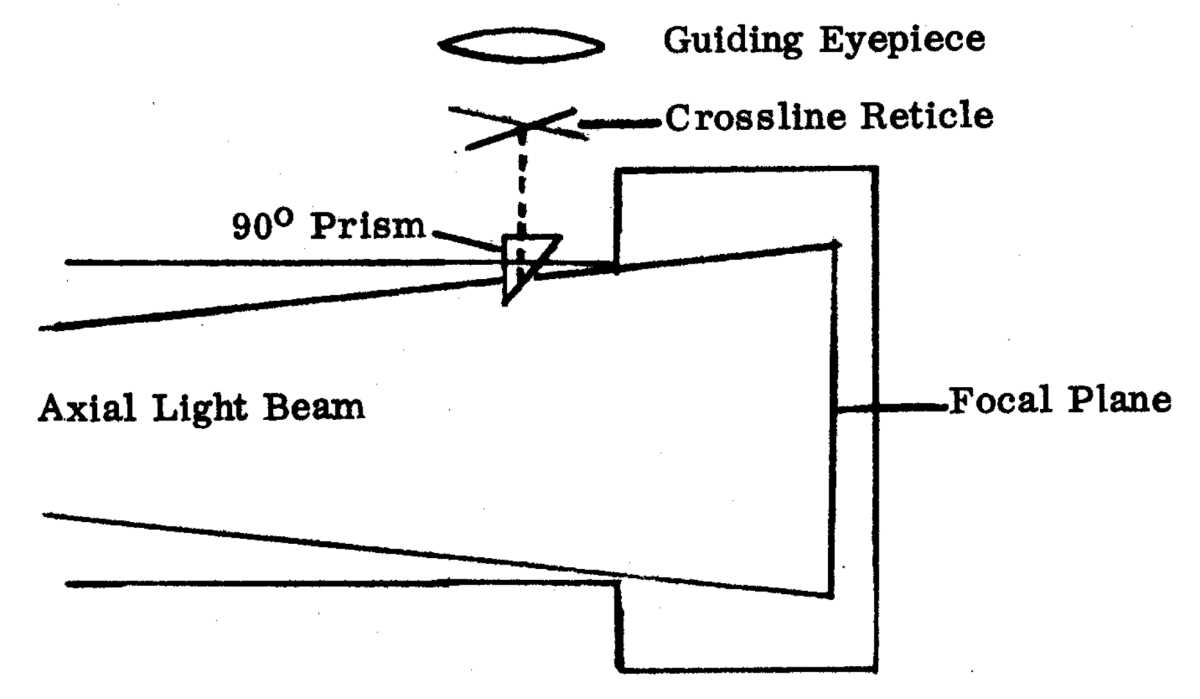

In its leaflet, Questar credited Hubert Entrop for developing a solution: an offset guiding system that was similar to those used by professional observatories. It consisted of a tiny right-angle prism built into the coupling between the telescope and the camera. The prism extracted a small percentage of the light from the telescope’s main optics. By using any reasonably bright star as a reference point, one could use an illuminated crosshair reticle eyepiece to keep that guide star positioned in the same place and make the necessary drive rate corrections using the Powerguide controller. “We are proceeding with development of an offset guiding attachment as a Questar accessory and expect to announce its availability later this year.”[35]

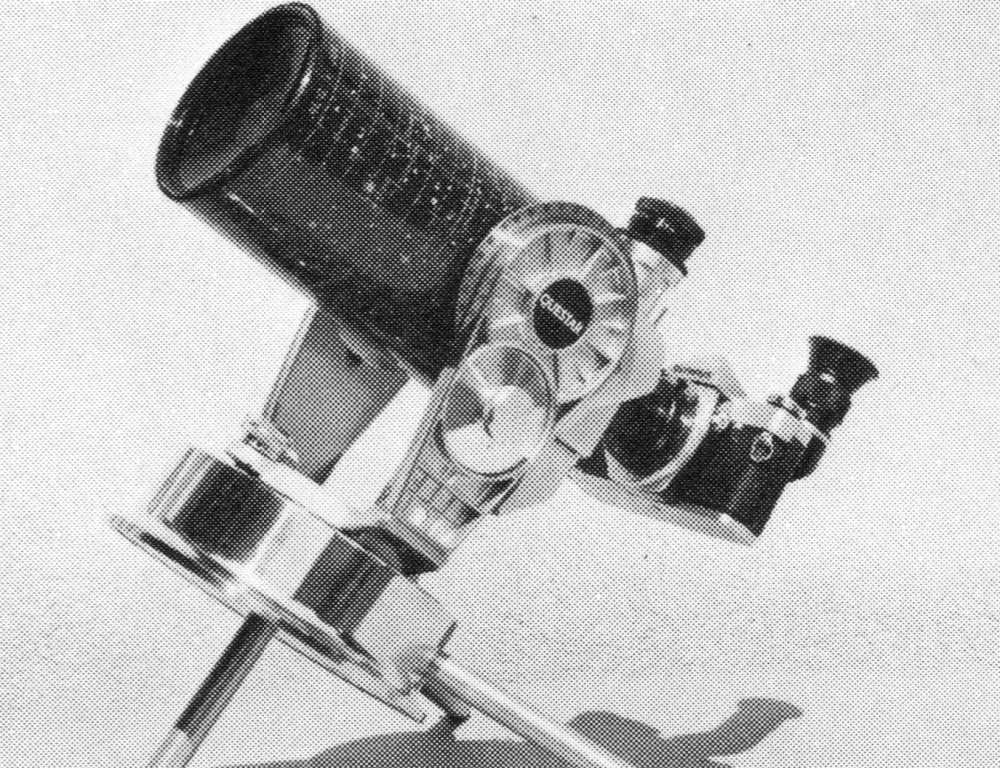

After making passing mention of the new accessory in the company’s 1972 booklet,[36] Questar introduced the Starguide in earnest in the March 1973 issue of Sky and Telescope. Demonstrating what was possible by including seven images of deep-space objects that Entrop had captured using his 3.5-inch Questar, the company wrote that “we are so impressed with his recent achievements that we hasten to bring you our new guiding system, based on his thinking and experimentation, which we have been at work on for some time.”[37]

The Questar Starguide consisted of numerous parts. First, it had a prism that directed a small amount of light to a guiding eyepiece that could be swiveled 360 degrees. The assembly also had a shutter for blocking light while the user made the necessary tracking corrections. Connected to the declination drive system was a vernier drive, whose gearbox and flexible cable control allowed the user to make ten-to-one corrections. Right ascension adjustments were made using the Powerguide controller.[38]

Hubert Entrop’s contribution represented the final element of a complete group of innovations whose other pieces Robert Little had conceived of in earlier years. In addition to the drive controller and illuminated reticle eyepiece that Little developed, Entrop introduced a way to monitor the tracking of a telescope with a high degree of accuracy.

Entrop’s Astrophotography

With the benefit of his Starguide, Hubert Entrop went on to become a prolific deep-space astrophotographer. Along with his 3.5-inch instrument, he added a Questar Seven to his equipment collection and produced a large number of images with both. On top of refining his darkroom technique, he continued to experiment with Kodak 103AO black-and-white film before discovering that color slide film gave him images with better resolution. Questar also supplied Entrop with telescopes equipped with Pyrex, quartz, and Cer-Vit mirrors for testing. He was most satisfied with Pyrex, the company’s standard option.[39]

By the late 1970s, Entrop had sent the company so many images that it dedicated the spring 1978 edition of its Questar Observations newsletter to presenting a sampling of them. In the accompanying text, Entrop recounted how he sometimes worked under extreme conditions including one session at Dragoon Pass in Arizona, where he encountered wind gusts in excess of fifty miles per hour. His Questar managed just fine.[40]

Entrop possessed an unyielding dedication to astrophotography. Alan Macfarlane remembered his routine:

He would pack up his telescope gear in his Volkswagen beetle, and at 3rd quarter moon, would drive down to Westgard Pass in California, shoot for 4 or 5 nights in the dark of the moon, and then drive back just in time to develop what he had shot, and then off again. Often Herm Dittmar would drive down with him, and the two would go through the same Japanese tea ceremony together. All this was with slow film, small apertures, field rotation, and questionable weather, but pioneering spirit. Hugh Entrop’s work is a great example of skill being more important than equipment. His equipment was great, but it is the factor of his consummate skill that has produced those amazing photographs.[41]

Beyond acknowledging his skillfulness in astrophotography, Alan Macfarlane remembered Entrop as a mensch.

“Hugh has a sparkling outlook, a definite humorous approach, and has helped me and many of you with a completely unselfish heart. We have treasured his friendship. What does one say about one’s mentor? I’ve learned so much from this gentleman! Hugh Entrop has done so much for all of us, astronomy, particularly astrophotography, and shown the world what can be accomplished with small telescopes and superb, marvelous talent!”[42]

Hubert Entrop died on October 25, 2003, at the age of 80. He never married, and he had no children.[43]

Camera Bodies

After Lawrence Braymer’s death at the end of 1965, others at Questar continued his campaign to persuade the camera industry’s to produce a vibrationless camera that was better suited to telescopic photography. Before Questar came along, as the company wrote in its 1968 booklet, “no camera manufacturer had given much thought to the problem because no one had complained about it.” For years, the company had been pointing out that vibration had to be removed from the camera in order to achieve sharp images with long-focus lenses.[44]

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, Questar was finally starting to see progress. Integrated light metering, brighter finder systems, and more control over vibration were all starting to appear as standard features in camera bodies that, at long last, were better suited for use with a Questar telescope.

Beseler Topcon Super D

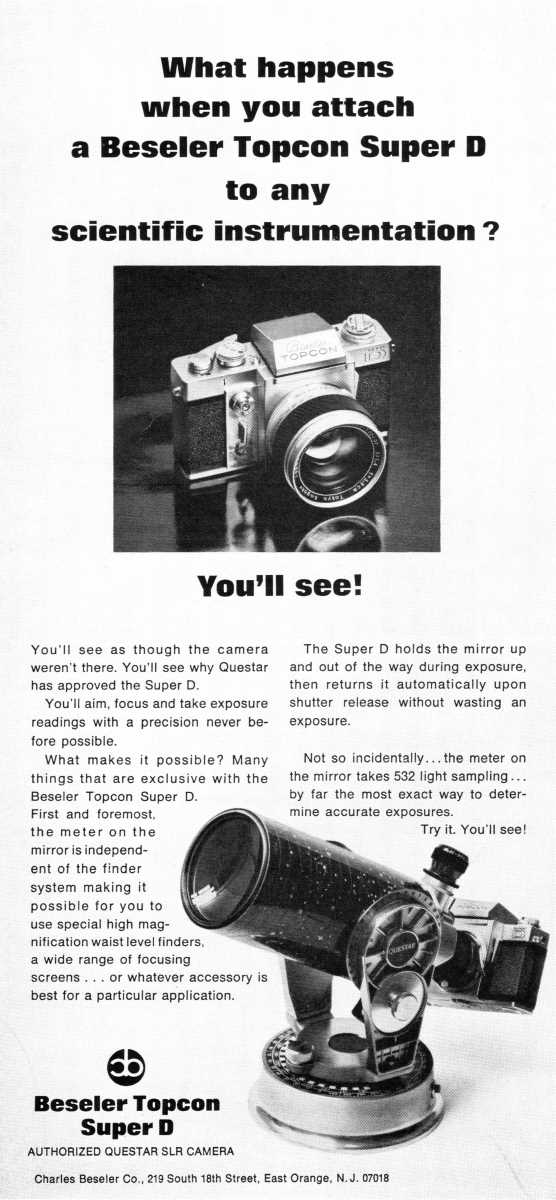

One camera that drew Questar’s attention was the Beseler Topcon Super D. Founded in 1868, the Charles Beseler Company began selling photographic equipment in 1953. Beseler often imported products manufactured by Tokyo Optical Company, which was also known as Tokyo Kogaku and later as Topcon, and branded them under its own name.[45]

In 1963, Tokyo Optical Company introduced the Topcon RE Super, an SLR camera with an Exakta-style lens mount. In the United States, Beseler imported this camera and marketed it under its own branding as the Topcon Super D. Although the prototype Asahi Pentax Spotmatic, which made its first appearance at Photokina in 1960, was the first SLR to feature through-the-lens (TTL) light metering, Beseler’s offering beat the Spotmatic to the market by a year. Its CdS photocells were situated behind a reflex mirror with narrow transparent lines that allowed a small percentage of light to pass to the meter, and it utilized a whole-scene averaging pattern.[46]

In the October 1967 issue of Scientific American, Beseler ran an advertisement featuring its Topcon Super D attached to a Questar, whose maker “has approved the Super D.” The promotion highlighted the independence of the camera’s light meter from its finder system. It also allowed for the use of high-magnification waist level finders or a range of focusing screens.[47]

Questar waited ten months to run an advertisement of its own featuring the Topcon Super D. In the August 1968 issue of Scientific American, the company coordinated with Beseler to place a pair of ads on facing pages. On one side, Beseler declared that the Super D “adds a new dimension to Questar photography.” It emphasized its high-magnification waist level finder, “which makes it possible for you to focus the camera to your eye before focusing the Questar to the subject.” Beseler noted the advantages of its built-in light meter and the degree to which the user could control the reflex mirror and shutter independently.[48]

On the facing page, Questar saluted “a great camera that has come to grips with the three factors on which successful high-resolution photography depends: total lack of vibration, sharp focus, and correctly thin negatives.” Questar claimed that, when it began writing about the problems that telescopic photography presented, solutions for these problems were virtually nonexistent. “But the state of the art has come a long way in the last decade.” The Questar-exclusive modification “permits independent control of mirror and shutter,” the high-magnification waist level finder with eyepiece makes achieving sharp focus easy, and the Beseler’s light meter provides accurate readings for setting correct exposure times.[49]

The Charles Beseler Company continued its own series of promotions. In the September 1968 issue of Popular Photography, for instance, it bragged that the Beseler Topcon Super D had become “an official camera.” In a full-page advertisement laden with the theme of classified surveillance for the purpose of national security, the company quipped that it was “not allowed to state with whom and where. Except in one case. Questar. The Super D is now the official Questar camera.”[50] And indeed, the camera began assuming greater prominence in Questar’s own marketing literature.

In an undated flyer entitled “Additional Camera Information,” Questar commented extensively on its belief that the Topcon Super D had become its camera of choice for photography with the Questar. “We have a definite preference for the modified Topcon Super D, since it has certain advantages for the demanding art of telephotography.” The company pointed out the advantages of the light meter’s location on the reflex mirror, an arrangement that did not tie the meter to the viewfinder as was the case with the Nikon F Photomic, and the high-magnification waist level finder, which accommodated near- or far-sighted users without the need for special diopter lenses. Questar also highlighted the finder’s clear focusing screen. Unlike many other ground glass screens which featured a translucent finish that scattered a great deal of light, the Beseler waist level screen was “as sharp and bright as the field in the telescope eyepiece itself.” It was a critical feature for low-light lunar or planetary photography, where the images did not have sufficient light for achieving good focus on more typical ground glass screens.[51]

The Questar-modified Beseler Topcon Super D made its last appearance in the company’s promotional literature in 1973.[52]

Olympus OM-1

By the early 1970s, camera manufacturers had caught on to offering photographers such features as a reflex mirror release and integrated TTL light metering. Before long, sellers were marketing numerous camera bodies with these and numerous other enhancements.

At Photokina in 1972, Olympus introduced its own groundbreaking camera as the M-1. After Leica complained that the name was too similar to its own M1 rangefinder camera, Olympus quickly renamed its new product the OM-1. This all-mechanical camera offered a compact design, a large viewfinder, a full-aperture CdS light meter, and a wide Bayonet lens mounting system.[53]

The OM-1 was an immediate success, and Olympus became the star of the entire photographic industry almost overnight.[54] In stark contrast with the big and heavy Topcon, the OM-1 kicked off a trend for lightweight, compact, and quiet SLRs that spread to other manufacturers throughout the rest of the 1970s.[55] In many ways, it was the very type of camera body that Lawrence Braymer sought decades prior.

Following its first appearance in some copies of a revised 1973 printing of its price catalog, Questar introduced its custom-modified version of the Olympus OM-1 across its magazine advertising for September 1974. In Sky and Telescope, for instance, the company echoed the sentiment of the market as a whole when it wrote that its “enthusiasm for this newest achievement in camera design is based on its tiny size and light weight as well as its ultra-quiet and nearly vibrationless action. Hold it in your hand and trip the shutter: what do you feel? Not a tremor! It’s the smallest! It’s the lightest! It’s the most!”[56]

Since the normal production Olympus OM-1 already came with the ability to move the reflex mirror out of the way before making an exposure, the Questar-specific modification consisted simply of an additional small lever screwed into the existing mirror lock-up control, a lever that merely assisted with the control’s operation. Whereas the company had shipped its Nikon F and Beseler Topcon Super D cameras with a sticker indicating that they were modified for Questar, the OM-1 bodies that the company sold had no such indication.[57]

Questar marketed its modified OM-1 camera body until 1987.[58]

Movie Film Equipment

In his 1964 Questar booklet, Lawrence Braymer made passing mention of movie cameras. Although they were seeing increased adoption by the mid-1960s, Braymer noted that they presented unique problems when paired with a Questar telescope. One challenge was that both 16 and 8mm movie cameras exposed a far smaller area of film and thus had worse resolution than still 35mm exposures.[59]

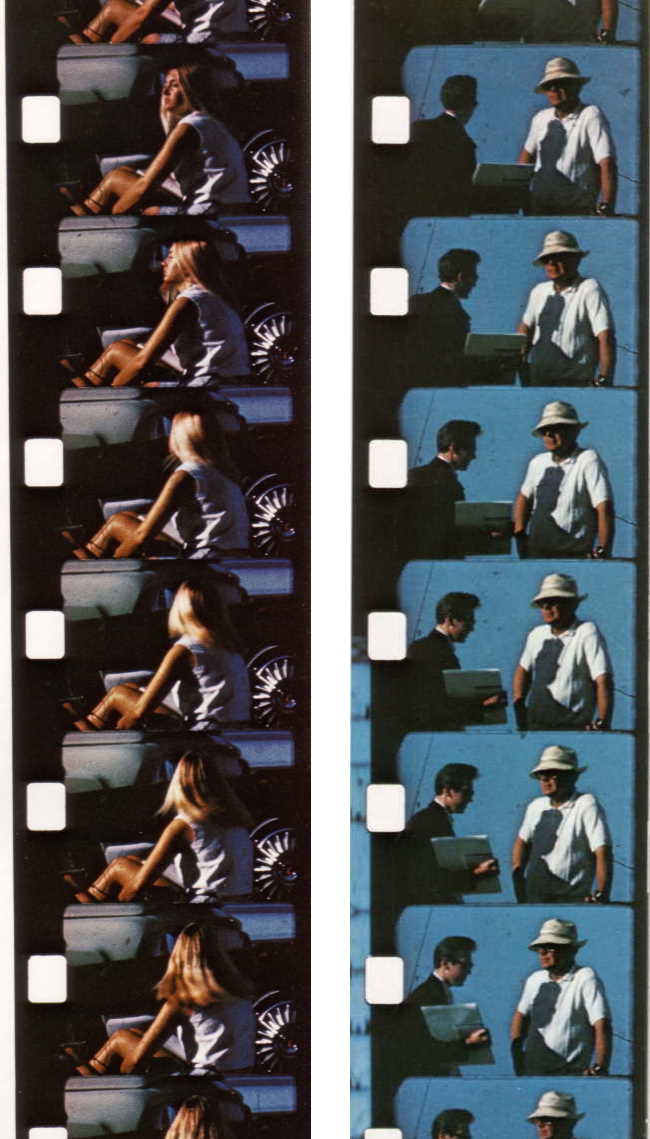

Nevertheless, Questar continued to explore possibilities. In its 1968 booklet, the company presented two samples of movie film strips that demonstrated how a Questar telescope could be used to capture images in motion. As was the case with still-image photography, good light, good seeing, and vibration-free equipment were all essential for making movies. The future looked bright: the emergence of better film in the coming years promised better results.[60]

Beaulieu Movie Cameras and Accessories

Introduced by Eastman Kodak in 1923, 16mm movie cameras failed at first to catch on among professional filmmakers, but they became widely used among amateurs. After photographers used the format extensively in the field during World War II, however, 16mm cameras dramatically gained market share during the postwar years. Business, government, and educational buyers quickly adopted the technology for their purposes, and a wide network of manufacturers cropped up in the 1950s and 1960s to meet their demand for equipment.[61]

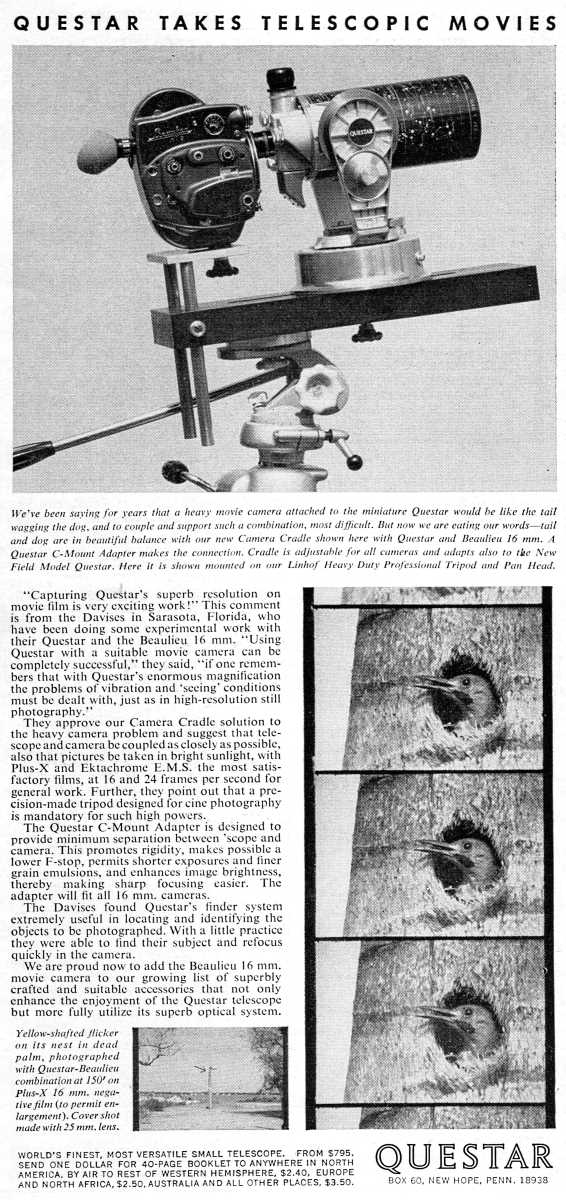

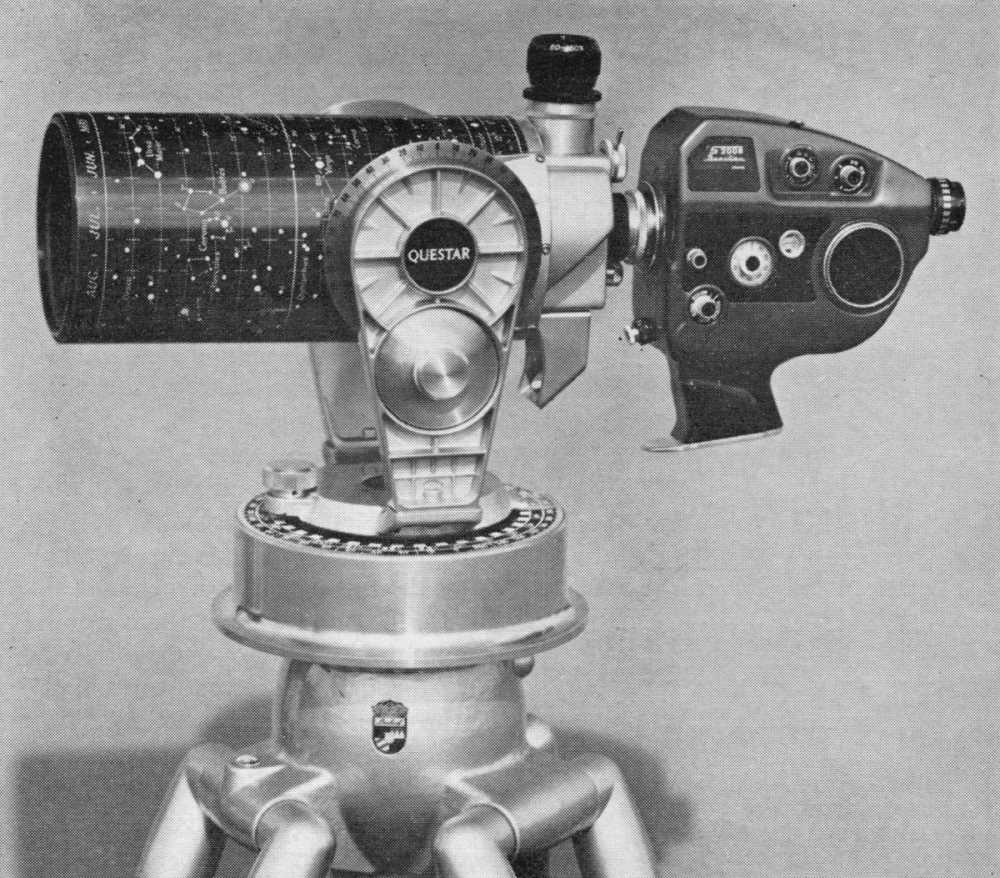

Some owners of Questar telescopes also saw opportunities for taking high-power movie footage. Eager to adopt the latest in photographic technology, Dorothy and Ralph Davis expressed how excited they were to experiment with using a movie camera with their Questar telescope. Their equipment was the R16ES, an electrically-driven hand-held instrument that accepted 16mm film. It was made by Beaulieu, a manufacturer of movie cameras in France. Introduced in Questar’s advertisements appearing in the November 1966 issues of Natural History and Scientific American magazines, the Beaulieu R16ES appeared alongside a sample section of movie film that the Davises took of a yell0w shafted flicker in its nest in a palm tree.[62]

In its September 1967 price catalog, Questar added more details. The Beaulieu R16ES featured an electric motor and a behind-the-lens light meter. Its transistorized speed control—notable because transistor technology was still relatively new in the 1960s—allowed the user to adjust the filming rate between two and 64 frames per second. The Beaulieu R16ES represented a premium piece of film equipment: at a price of $989.50, it alone approached the cost of a Standard Questar.[63]

The company also offered a handful of accessories that enhanced the experience of moviemaking with its telescopes. In November 1966, Questar introduced a C-mount adapter for attaching movie cameras and other accessories with a minimum of separation. A closer connection between telescope and camera translated into far more rigidity, lower focal ratios, shorter exposure times, and brighter images.[64]

Earlier that year, Questar also began offering the Camera Cradle. “Attaching a heavy camera to the 7-pound Questar is a little like the tail wagging the dog,” the company wrote in its April 1966 price catalog, so it developed a platform for both telescope and camera to rest on. The new accessory supported the weight of heavy equipment like the four-pound Beaulieu R16ES so that the telescope would not bear all of its wrenching momentum force. It also accommodated camera bodies attached to Questars with an unusually long chain of extension tubes for high-magnification photography.[65]

Enthusiasts who may have been put off by the relatively large size of 16mm movie film cameras that made accessories like the Camera Cradle necessary soon found alternatives appearing on the market. In 1965, Eastman Kodak introduced the Super 8 movie film format at the world’s fair in New York. With the benefit of convenient light-proof film cartridges that went into compact cameras, home movie filmmakers quickly adopted the technology.[66]

Not long after introducing the Beaulieu R16ES, Questar began marketing the Beaulieu Super 8 movie camera. In spite of its smaller-format 8mm movie film, this “little giant,” in the words of Dorothy and Ralph Davis, was “a peach.” They attested to its complete automation, flexible filming rates, reflex viewfinder, and built-in light meter. The Beaulieu Super 8 made its first appearance in Questar’s magazine advertising in June 1967, and the company sold it for $699.[67]

That same month, Questar also began offering the Miller Fluid Head. Designed for smooth panning while making movie footage, this accessory operated using a semi-hydraulic construction. It could be used with any standard tripod.[68]

Beaulieu movie cameras continued to appear in Questar promotional literature until the late 1980s.

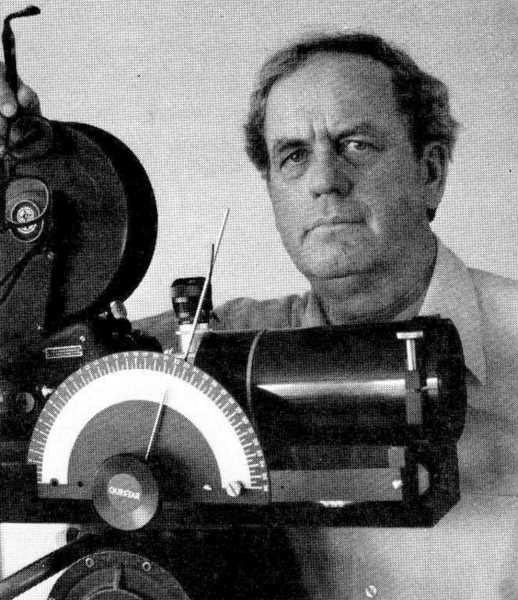

David Quaid and the Cinema Model

Soon, professional cinematographers were taking notice of what the Questar telescope could offer them. One such individual was David Quaid. Born in New York in 1920, he began learning his craft during the Great Depression. Without the benefit of a formal college education, Quaid and his friend Warren Rothenberger scrimped and saved for their first movie camera and taught themselves how to use it. In a lucky break, they caught the attention of Paramount’s news reel division when they used their first roll of film to capture a riot between police and union workers on film. Later, Quaid went on to serve as a battlefield cameraman in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Back home in the United States, he filmed television commercials before breaking into filming movie productions. Over a thirty-year period beginning in 1954, Quaid was the credited cinematographer for at least a dozen works.[69]

A perfectionist whose curiosity drove much of his career, Quaid developed new types of gels and filters, an automatic exposure system for stop-action photography, and camera modifications using X-ray technology that allowed for low-light motion picture filming. For The Swimmer (1968), a surreal drama starring Burt Lancaster, he used a zoom lens for the bulk of his filming work.[70]

The experience triggered an inspiration. Soon after finishing his work on The Swimmer, Quaid acquired a Questar telescope and continued his experiments with long-focus cinematography. He ultimately spent three years in a persistent effort to adapt an instrument that was designed primarily for astronomical observing and make it into a new and unique tool for moviemaking. At first, the individuals at Questar had been skeptical. But with their help, Quaid overcame challenges presented by the telescope’s long focal length, its susceptibility to vibration, and a focusing system that was primarily geared for working at infinity.[71]

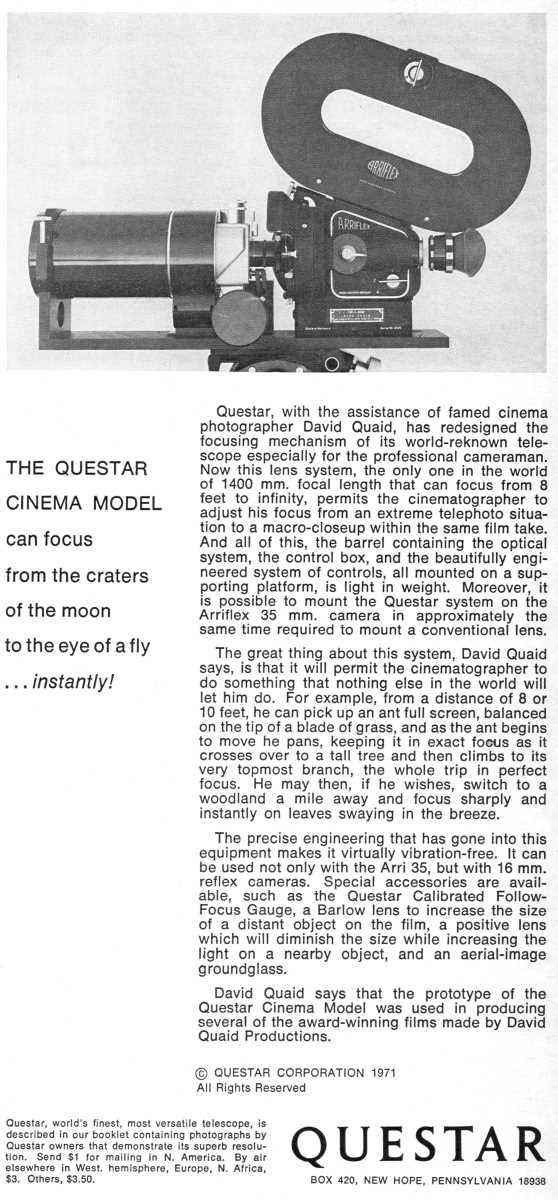

In June 1971, the results of his work appeared in passing mention in one of Questar’s advertisements in Scientific American magazine.[72] Four months later, the company made an all-out announcement of its new product, the Cinema Model. In its advertisement, Questar boasted that it could “focus from the craters of the moon to the eye of a fly... instantly!” The company continued to write that, with David Quaid’s assistance, Questar “has redesigned the focusing mechanism of its world-reknown [sic] telescope especially for the professional cameraman.” It allowed the cinematographer to adjust focus from extreme telephotographic targets to extreme closeups in a same take. The lightweight apparatus was mounted on its own platform and accepted the Arriflex 35mm camera and 16mm reflex cameras. “The great thing about this system, David Quaid says, is that it will permit the cinematographer to do something that nothing else in the world will let him do.” For example, it could keep an ant in focus and pan with it as it moves to the topmost branch of a tree. Available accessories included the Questar Calibrated Follow-Focus Gauge, a Barlow lens, a positive lens, and an aerial-image ground glass.[73]

In the April 1972 issue of Scientific American, Questar described how David Quaid used the Cinema Model to create a reel of test footage. He filmed a number of subjects—a moonset and sunset, a train running along the Hudson River, the New York skyline, a grazing cow, and two aircraft taking off from Newark Airport—all at long distance. At no point did Quaid change lenses.[74]

In spite of its ingeniousness, the Cinema Model was never more than a niche product. It made its last appearance in the company’s printed literature in 1987.[75]

Fast Focus

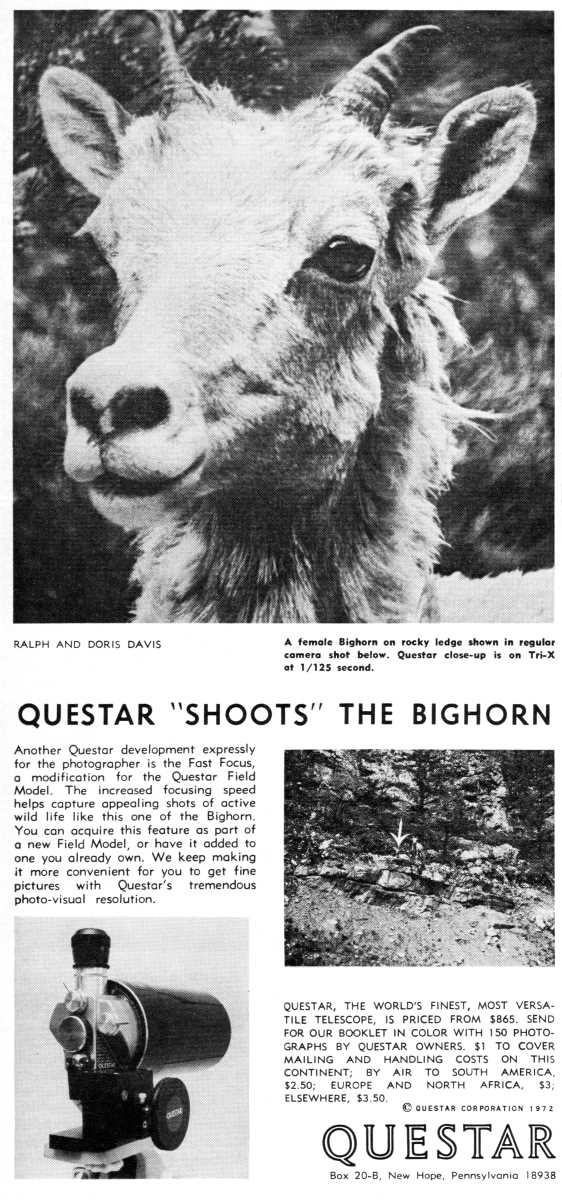

After David Quaid helped Questar develop the Cinema Model, the company took what it had learned about modifying its focuser and adapted the changes for more general use with the Field Model.

In an undated flyer, Questar offered more details about what it called the Fast Focus option. “Unlike the regular threaded rod which takes 10 turns to go from infinity to 25 feet,” the Fast Focus mechanism “consists of a sliding focus rod whose position is accurately determined by a cam moved by a handwheel.... The main advantage of the Fast Focus is the speedier acquisition and focus of active wildlife.” Because of its greater bulk, this option was available only with the Field Model. The fork mount of the Standard Questar prevented its implementation on that instrument.[76]

The earliest indication that Questar had incorporated the Fast Focus option into the Field Model emerged in a brief advertisement in the June-July 1972 issue of Natural History magazine.[77] Later in December, Questar published more details about the Fast Focus modification in Scientific American. “The increased focusing speed helps capture appealing shots of active wild life.... You can acquire this feature as part of a new Field Model, or have it added to one you already own.”[78]

Between 1983 and 1989, Questar offered the Fast Focus II option, which replaced the complex and bulky cam-based mechanism of the earlier version with a simplified and more compact rack-and-pinion assembly.[79]

Television Equipment

Questar did not limit itself to accomodating movie film cameras. Two other products geared specifically for television applications appeared briefly during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

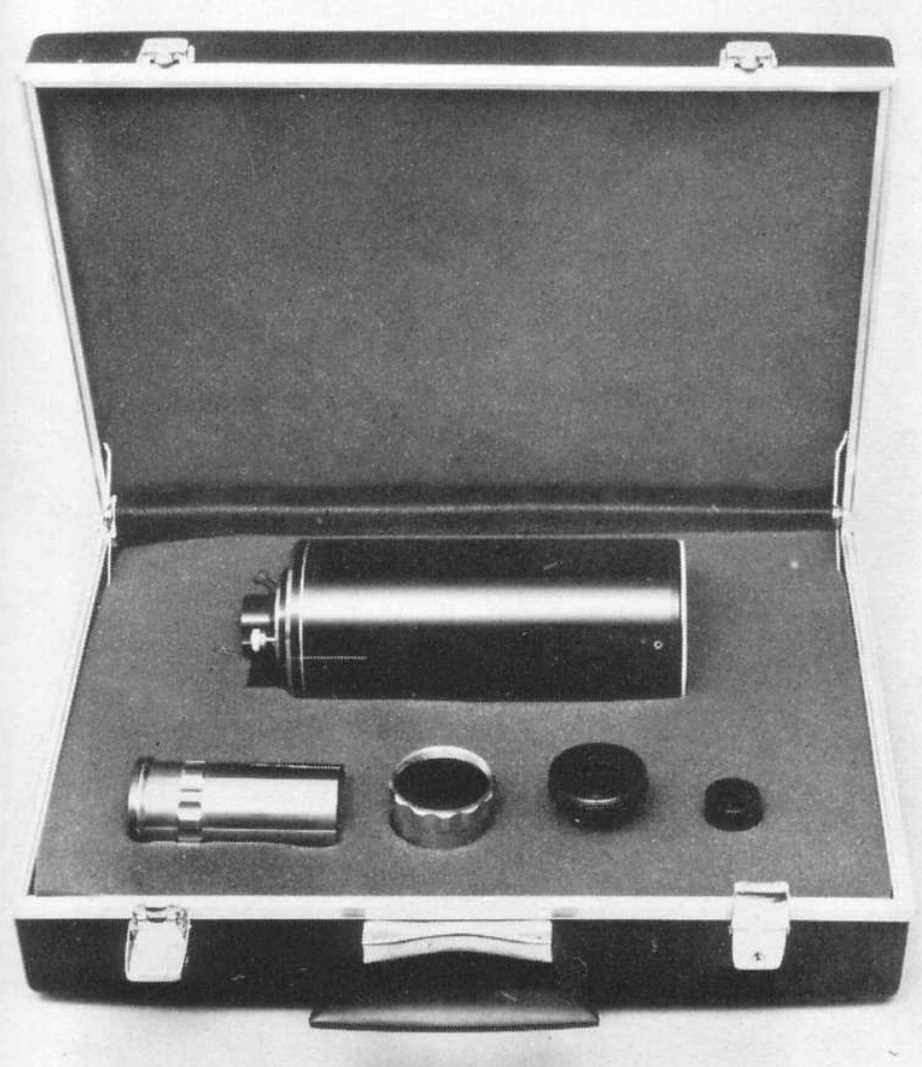

Questar TV Model

In Questar’s April 1966 price catalog, the company featured the Questar TV Model. It bore striking resemblance to the Field Model, and it even included the same hard-shell carrying case. But it represented more of a stripped-down unit that lacked key features like a control box. Otherwise, it contained the same optical system as all other instruments made by Questar. Developed with the assistance of a crew equipped with a field truck and television cameras, the unit could focus on objects as close as 25 feet away given the television camera’s ortho tube could accommodate such a distance. It was compatible with RCA’s lens turret. Questar sold the TV Model for $1000.[80]

Not long after Questar introduced the TV Model, ABC used it with a television camera onboard the U.S.S. Guadalcanal to photograph the recovery of Gemini 10, which landed on July 21, 1966. “The Questar is a great lens,” wrote William Waterbury, “especially when the parachute and capsule fill the vertical frame at 7 1/2 miles, as they did on GT-9.”[81]

ABC also used Questar optics during its coverage of the Winter Olympics at Innsbruck in 1964 and at Grenoble in 1968.[82]

The Questar TV Model appears to have been short lived. After making another appearance in Questar’s September 1967 price catalog, it vanished from the company’s marketing literature.[83]

Questar Television Camera

Another fleeting offering was the similarly-named Questar Television Camera, which first appeared in the company’s magazine advertising in the June 1971 issue of Scientific American.[84] This relatively compact product served a variety of applications including the monitoring of machining processes at a safe distance, the inspection of tall structures without the need for hazardous climbing, or the viewing of medical operations without distracting the surgeon. But its most obvious use was for video surveillance.[85]

Although the Questar Television camera continued to show up in marketing literature illustrations as late as the early 1980s, the instrument’s appearance in Questar magazine advertisements was short-lived. The company mentioned the Questar Television Camera for the last time in the October 1972 issue of Modern Photography.[86]

While the late 1960s and early 1970s were heady times for photographic innovations at Questar, other developments of a more general nature were unfolding for the company’s instruments.

Notes

1 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript; Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, July 1964, 25-36.

2 C.L. Stong, “The Amateur Scientist,” Scientific American, December 1965, 106; Dan Harrison, “Robert Little Is Dead at 77,” Eyepiece: Journal of the Amateur Astronomers Association of New York, January 2011, 1, https://www.aaa.org/EyepieceFiles/aaa/2011_01_January_Eyepiece.pdf, accessed August 3, 2020.

3 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, November 1960, 11.

4 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1968, inside front cover.

5 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, October 1958, with addenda, June 1959, 28.

6 Questar Corporation, price catalog, 1964.

7 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, September 1965, inside front cover.

8 Questar Corporation, price catalog, April 1, 1966.

9 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1970, inside front cover.

10 Questar Corporation, “Instructions—Varitrac II,” n.d.

11 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1968, 16-17.

12 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, February 1969, inside front cover.

13 Terence Dickinson, “World’s Finest Portable Telescope,” ‘Scope, vol. 7, no. 2, (March 1969).

14 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1970, inside front cover; Jim Perkins, “Questar Serial Number Systems” (unpublished manuscript, August 20, 2020), typescript.

15 Ralph Foss, “Questar Timeline” (unpublished manuscript, September 22, 2007, revised September 19, 2009), typescript.

16 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1970, inside front cover.

17 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, April 1970, inside front cover.

18 Robert T. Little, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, November 1976, 353.

19 Dan Harrison, “Robert Little Is Dead at 77,” Eyepiece: Journal of the Amateur Astronomers Association of New York, January 2011, 1, 12, 14, https://www.aaa.org/EyepieceFiles/aaa/2011_01_January_Eyepiece.pdf, accessed August 3, 2020.

20 J. Patrick Coolican, “Hubert Entrop Helped Make Airplanes Safe and Boats Fast,” Seattle Times, November 4, 2003, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=20031104&slug=entropobit04m, accessed May 13, 2020.

21 J. Patrick Coolican, “Hubert Entrop Helped Make Airplanes Safe and Boats Fast,” Seattle Times, November 4, 2003, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=20031104&slug=entropobit04m, accessed May 13, 2020; Alan Macfarlane, “Hugh Entrop: SAS’s Pioneer Astrophotographer,” Webfooted Astronomer, October 2002, 3, http://archive.seattleastro.org/webfoot/WebOct02.pdf, accessed May 13, 2020.

22 “Outboard Racing Legends - Past & Present,” Quincy Looper, n.d., http://www.quincylooperracing.us/gpage5.html, accessed May 13, 2020.

23 “Outboard Motor World Speed Record,” Seabuddy on Boats, 2009, http://www.seabuddyonboats.com/motors-and-power/outboard-motor-world-speed-record/, accessed May 13, 2020; “Outboard Racing Legends - Past & Present,” Quincy Looper, n.d., http://www.quincylooperracing.us/gpage5.html, accessed May 13, 2020; J. Patrick Coolican, “Hubert Entrop Helped Make Airplanes Safe and Boats Fast,” Seattle Times, November 4, 2003, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=20031104&slug=entropobit04m, accessed May 13, 2020.

24 “100 MPH Club, Gulf Oil Corporation, 1949-1968,” The Vintage Hydroplanes, n.d., https://www.vintagehydroplanes.com/apba_history/100_mph_club/gulf100mphclub.html, accessed May 13, 2020.

25 “Powerboat Results,” Sports Illustrated, November 16, 1959, https://vault.si.com/vault/1959/11/16/powerboat-results, accessed May 13, 2020.

26 “Outboard Racing Legends - Past & Present,” Quincy Looper, n.d., http://www.quincylooperracing.us/gpage5.html, accessed May 13, 2020.

27 J. Patrick Coolican, “Hubert Entrop Helped Make Airplanes Safe and Boats Fast,” Seattle Times, November 4, 2003, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=20031104&slug=entropobit04m, accessed May 13, 2020.

28 J. Patrick Coolican, “Hubert Entrop Helped Make Airplanes Safe and Boats Fast,” Seattle Times, November 4, 2003, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=20031104&slug=entropobit04m, accessed May 13, 2020.

29 Alan Macfarlane, “Hugh Entrop: SAS’s Pioneer Astrophotographer,” Webfooted Astronomer, October 2002, 3-4, http://archive.seattleastro.org/webfoot/WebOct02.pdf, accessed May 13, 2020; J. Patrick Coolican, “Hubert Entrop Helped Make Airplanes Safe and Boats Fast,” Seattle Times, November 4, 2003, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=20031104&slug=entropobit04m, accessed May 13, 2020.

30 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1990, inside front cover.

31 Alan Macfarlane, “Hugh Entrop: SAS’s Pioneer Astrophotographer,” Webfooted Astronomer, October 2002, 3, http://archive.seattleastro.org/webfoot/WebOct02.pdf, accessed May 13, 2020.

32 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1968, 23; Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1972, 21.

33 Alan Macfarlane, “Hugh Entrop: SAS’s Pioneer Astrophotographer,” Webfooted Astronomer, October 2002, 3-4, http://archive.seattleastro.org/webfoot/WebOct02.pdf, accessed May 13, 2020.

34 Questar Corporation, “Deep Sky Photography Through the Questar,” n.d.

35 Questar Corporation, “Deep Sky Photography Through the Questar,” n.d.

36 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1972, 5.

37 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1973, inside front cover.

38 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1973, inside front cover.

39 Alan Macfarlane, “Hugh Entrop: SAS’s Pioneer Astrophotographer,” Webfooted Astronomer, October 2002, 4, http://archive.seattleastro.org/webfoot/WebOct02.pdf, accessed May 13, 2020.

40 Questar Corporation, Questar Observations (Spring 1978).

41 Alan Macfarlane, “Hugh Entrop: SAS’s Pioneer Astrophotographer,” Webfooted Astronomer, October 2002, 4, http://archive.seattleastro.org/webfoot/WebOct02.pdf, accessed May 13, 2020.

42 Alan Macfarlane, “Hugh Entrop: SAS’s Pioneer Astrophotographer,” Webfooted Astronomer, October 2002, 3-4, http://archive.seattleastro.org/webfoot/WebOct02.pdf, accessed May 13, 2020.

43 Hubert Entrop Obituary, Seattle Times, October 30, 2003, https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/seattletimes/obituary.aspx?n=hubert-entrop-hugh&pid=1554109, accessed May 13, 2020.

44 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1968, 21.

45 “Beseler,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Beseler, accessed January 30, 2021; “Tokyo Kogaku,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/T%C5%8Dky%C5%8D_K%C5%8Dgaku, accessed January 30, 2021.

46 “Topcon RE Super,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Topcon_RE_Super, accessed January 30, 2021; “Pentax Spotmatic,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Pentax_Spotmatic, accessed November 11, 2021; Todd Gustavson, Camera: A History of Photography from Daguerreotype to Digital (New York: Sterling Innovation, 2009), 301.

47 Charles Beseler Company, advertisement, Scientific American, October 1967, 49.

48 Charles Beseler Company, advertisement, Scientific American, August 1968, 44.

49 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, August 1968, 45.

50 Charles Beseler Company, advertisement, Popular Photography, September 1968, 5.

51 Questar Corporation, “Additional Camera Information,” n.d.

52 Questar Corporation, Instruments and Accessories catalog, 1973, revision 3.

53 “Olympus OM-1/2/3/4,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Olympus_OM-1/2/3/4, accessed January 30, 2021.

54 Todd Gustavson, Camera: A History of Photography from Daguerreotype to Digital (New York: Sterling Innovation, 2009), 314.

55 John Wade, Retro Cameras: The Collector’s Guide to Vintage Film Photography (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 36.

56 Questar Corporation, price catalog, revised printing 1973, no. 3; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, September 1974, inside front cover; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, September 1974, 208.

57 Olympus OM-1 instructions, n.d., 29, https://www.cameramanuals.org/olympus_pdf/olympus_om-1.pdf, accessed January 30, 2021; Alt-Telescopes-Questar Majordomo list message, December 4, 1998, digest 307, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/Alt-Telescopes-Questar%20Digests/, accessed October 14, 2019; Ralph Foss, “Questar Timeline” (unpublished manuscript, September 22, 2007, revised September 19, 2009), typescript.

58 Questar Corporation, Instruments and Accessories catalog, 1987.

59 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, July 1964, 31.

60 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1968, 24-25.

61 “16 mm film,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/16_mm_film, accessed January 31, 2021.

62 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, November 1966, 6; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, November 1966, 9; “Beaulieu (company),” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaulieu_(company), accessed January 30, 2021.

63 Questar Corporation, price catalog, September 1, 1967.

64 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, November 1966, 6; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, November 1966, 9.

65 Questar Corporation, price catalog, April 1, 1966.

66 “Super 8 film,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Super_8_film, accessed January 31, 2021.

67 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, June-July 1967, 61; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, June 1967, 111.

68 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, June-July 1967, 61; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, June 1967, 111.

69 “David Quaid,” MyHeritage.com, n.d., https://www.myheritage.com/names/david_quaid, accessed December 19, 2020; “David Quaid,” Millimeter, May 1977, 35; “David Quaid, ASC,” International Photographer, March 1998, 40-41, 58-60; “David L. Quaid,” IMDB, n.d., https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0702779/, accessed January 30, 2021.

70 “David L. Quaid,” Chapman Family Funeral Homes, n.d., https://www.ccgfuneralhome.com/obit/david-l.-quaid, accessed February 17, 2020; “The Swimmer (film),” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Swimmer_(film), accessed January 30, 2021.

71 “David Quaid,” Millimeter, May 1977, 35; “David Quaid, ASC,” International Photographer, March 1998, 40-41, 58-60.

72 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, June 1971, 55.

73 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, October 1971, 41.

74 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, April 1972, 55.

75 Questar Corporation, instruction book, 1987, 35.

76 Questar Corporation, “Fast Focus,” n.d.

77 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, June-July 1972, 9.

78 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, December 1972, 82.

79 Billydee, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, November 16, 2017, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/598740-fast-focus-questar/?p=8218101, accessed April 22, 2021; Ben Langlotz, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, August 21 2019, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/673398-fast-focus-ii-technical-analysis/, accessed April 22, 2021.

80 Questar Corporation, price catalog, April 1, 1966.

81 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1972, 20.

82 Abby Rand, “The Winter Olympics,” TV Guide (Northern California), February 3-9, 1968. https://archive.org/details/vintage-tv-guides/TV%20Guide%201968-02-03%20Northern%20CA/page/n7/mode/2up, accessed November 16, 2022.

83 Questar Corporation, price catalog, September 1, 1967.

84 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, June 1971, 55.

85 Questar Corporation, price catalog, 1971.

86 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Modern Photography, October 1972, 8.