Chapter 4. The Steady Years

In This Chapter

During the first half of the 1960s, Lawrence Braymer and his colleagues at Questar had largely finished work on solidifying their product offerings. Before his passing in December 1965, the company had implemented a number of design changes to its core 3.5-inch telescope, and it introduced a simplified version in the form of a modernized Field Model. Other products were in the works. The Duplex Questar was about to be introduced to the market, and the Questar Seven was not far behind.

After Lawrence Braymer’s death, his wife Marguerite inherited her husband’s assets. In January 1964, he drew up a will and named her the beneficiary of a trust fund he had established. Clearly showing the success he had with his business, Braymer’s estate was worth almost a half-million dollars when it entered probate.[1]

Marguerite Braymer also inherited Questar Corporation and assumed its helm.[2] The company was already a success. Under her control in the late 1960s and early 1970s, she kept Questar moving steadily along its existing course. Its bread and butter continued to be its 3.5-inch Maksutov-Cassegrain telescope mounted in various ways.

Whatever new products that Questar introduced during this period were mostly limited to accessories that friends of the company conceived of. Perhaps it was appropriate this way. When Lawrence Braymer was starting his company, he was not alone. Norbert Schell, John Schneck, David Bushnell, Thomas Cave, J.R. Cumberland, Frank Godwin, and other colleagues all helped get Questar going. When his wife Marguerite took over the company after his death, it was only fitting that she too had help.

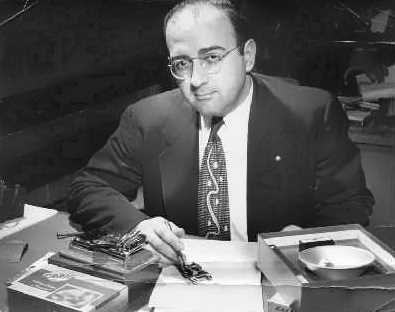

On the optical design front was Edward Kaprelian. As a young man during the Second World War—he was only 32 years old by the end of the conflict—Kaprelian served as head of the U.S. Army Signal Corps photo lab at Fort Monmouth in New Jersey. Later, he became chief engineer at Kalart Company, a manufacturer of cameras and projectors that was based in Connecticut.[3] Kaprelian eventually struck out on his own as an independent consultant. For Questar, he received and analyzed optical designs for a variety of the company’s instruments.[4] He was an inventor, too. Over the course of his entire career, he earned over fifty patents.[5] In his personal life, Kaprelian was an avid photographer. By the time of his death in 1997, he had amassed several hundred pieces of gear representing a wide sampling of the history of photography equipment.[6]

For many of its production needs, Questar turned to Robert Schwenk. Born in 1926, he spent his entire life in nearby Pottstown. After serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II, he got his start as an employee of Gerald Fegley, an independent machinist with whom the company had a strong relationship during its early years. Schwenk became one of Fegley’s best machinists. By the late 1960s or early 1970s, he struck out on his own and began Q Machinery. His one client was Questar. An old-school machinist who later was begrudgingly pulled into the world of numerical control and computer numerical control tooling, Schwenk did production work for the company until his retirement in 2000.[7]

Another friend of the company was Rodger Gordon. A native of eastern Pennsylvania, Gordon graduated from Pen Argyl High School in the upper two-fifths of his class in 1958. He later worked as a machine operator before landing a position at Edmund Scientific in New Jersey in 1967. His duties included providing customers with technical information and conducting optics tests on eyepieces and mirrors the company received from its supplier. In 1969, he returned to the Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania and redirected his career toward audio-visual sales for educational clients in the region.[8]

Gordon was also a serious amateur astronomer. At a Lehigh Valley Amateur Astronomical Society (LVAAS) Christmas party in December 1962, Gordon met his future wife, and the two were married in October 1963. His wife and his two children are all amateur astronomers. Gordon became a highly respected expert on eyepiece design. Over a number of years, he built a large collection of telescopes and other accessories.[9]

Not long after his graduation from high school, Gordon’s relationship with the company began the moment an elderly member of the LVAAS offered him a look through his Questar telescope. He was immediately hooked, but he could not afford one of his own. For the next eight years, he made do with what he had. His long-tube four-inch Unitron refractor and eight-inch reflector shook and shimmied more often than not when he tried to use them in a field that the locals called “Windy Hill farms.” In early 1966, he finally sold them, came up with another $200, and bought a Questar telescope in April. It was the first of five he eventually came to own. All of them stood up to the wind without any problem.[10]

In addition to his many testimonial letters which Questar included in its magazine advertising, Gordon also traveled with their telescopes and demonstrated them to interested parties as part of his dealings with educators at the elementary, secondary, and college/university levels.[11]

Questar also had an experienced group of in-house employees. John Schneck, Lawrence Braymer’s right-hand man for managing production, continued with the company.

Another individual that came onboard was Paul Schenkle. Born in New Jersey around 1926, his family had moved to Pennsylvania by the beginning of the 1940s.[12] Schenkle eventually pursued career as a professional optician. He was also a dedicated amateur astronomer who built his own telescopes. In April 1965, he joined the Lehigh Valley Amateur Astronomical Society and quickly accelerated his engagement with it. After serving as the club’s secretary and observing coordinator, he became its director in 1969.[13]

Schenkle came on board as one of Questar’s employees before the end of the 1960s.[14] Along with handling many other responsibilities, he applied the 3M Velvetone paint spot that shielded Questar’s secondary mirror.[15]

Outside of work, Paul Schenkle was close friends with Rodger Gordon. They along with Stan Wilkes and Bill McHugh were the “astronomical big four” who gathered every Saturday night regardless of the weather. If it was clear, they would observe. If the weather did not allow for observing, they sat and discussed optics and articles in the current issue of Sky and Telescope and Astronomy magazines. The group also compared and evaluated many eyepieces, telescopes, and accessories. With the “big four” meeting regularly, Gordon’s children grew up in a household steeped in astronomy. At the age of five, his daughter played chess with Shenkle and was later a member of her high school chess team.[16] His son became an amateur astronomer and Questar owner, too.

Edward Kaprelian, Robert Schwenk, Rodger Gordon, John Schneck, and Paul Schenkle were only some of the individuals who were closely associated with Questar in various capacities during the late 1960s and early 1970s. They and many others like them played a key role in bring about new products, making refinements to existing ones, and contributing to the company’s success.

While others helped, there was no question that Marguerite Braymer exercised firm control of the company after Lawrence’s death in December 1965. Although she lacked a technical background, she nonetheless had years of invaluable experience working alongside her husband during the company’s first fifteen years of existence. By the beginning of 1966, Questar had become her company. Others lent a hand and made important contributions, but she had final say.[17]

Marguerite’s experience in the advertising industry early in her career put her in an excellent position to take over much of Questar’s marketing in the absence of her husband. Although he probably did most of the copywriting during the company’s first decade, she most likely assisted him. This involvement further primed her for guiding the company’s marketing efforts when she assumed control of the company. Marguerite continued many of the same advertising themes Questar had used in prior years, and she created new ones to suit the times.

Questar saw its adoption and influence grow during the late 1960s and early 1970s. More celebrities became clients of the company, and the Questar telescope also appeared in several exhibitions around the world.

Notes

1 Ralph Foss, “Lawrence E Braymer” (unpublished manuscript, June 11, 2006, revised June 26, 2006), typescript, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed October 15, 2019.

2 Contemporary Authors: A Bio-bibliographical Guide to Current Writers in Fiction, General Nonfiction, Poetry, Journalism, Drama, Motion Pictures, Television and Other Fields (Gale Research Company, 1969), 307, https://archive.org/details/contemporaryauth5-8gale/page/307/mode/1up, accessed June 3, 2022; Who’s Who in America, 1992-1993 (New Providence: Marquis Who’s Who, 1992), volume 1, 392, https://archive.org/details/isbn_0837901480_1/page/392/mode/1up, accessed June 3, 2022; Ralph Foss, “Lawrence E Braymer” (unpublished manuscript, June 11, 2006, revised June 26, 2006), typescript, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/files/FAQ/, accessed October 15, 2019.

3 Jo Lommen, “The Kalart Press Camera,” Jo Lommen, n.d., https://lommen9.home.xs4all.nl/kalartcamera/index.html, accessed January 25, 2021; “Kaprelian Camera Collection - Nov. 19, 2011,” Fuller’s LLC, November 19, 2011, https://www.liveauctioneers.com/catalog/27015_kaprelian-camera-collection-nov-19-2011/, accessed January 22, 2021.

4 Jim Perkins, “Questar Serial Number Systems” (unpublished manuscript, August 20, 2020), typescript; Rodger Gordon to the author, September 23, 2020.

5 Jo Lommen, “The Kalart Press Camera,” Jo Lommen, n.d., https://lommen9.home.xs4all.nl/kalartcamera/index.html, accessed January 25, 2021.

6 “Kaprelian Camera Collection - Nov. 19, 2011,” Fuller’s LLC, November 19, 2011, https://www.liveauctioneers.com/catalog/27015_kaprelian-camera-collection-nov-19-2011/, accessed January 22, 2021.

7 Jim Perkins, email message to author, November 30, 2020; “John Robert Schwenk,” FindAGrave.com, n.d., https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/167183259/john-robert-schwenk, accessed January 25, 2021.

8 Rodger Gordon to the author, September 23, 2020.

9 Rodger Gordon to the author, September 23, 2020; “A Closer Look at High Magnification,” Brayebrook Observatory, n.d., http://www.brayebrookobservatory.org/BrayObsWebSite/HOMEPAGE/forum/highmagnifications.html, accessed August 15, 2020.

10 Rodger Gordon in discussion with the author, August 15, 2020; Rodger Gordon to the author, September 23, 2020.

11 Rodger Gordon in discussion with the author, August 15, 2020; Rodger Gordon to the author, September 23, 2020.

12 “Paul G Shenkle in the 1940 Census,” Ancestry.com, n.d., https://www.ancestry.com/1940-census/usa/Pennsylvania/Paul-G-Shenkle_rg004, accessed January 25, 2021.

13 Sandy Mesics, “Paul Shenkle at the Helm in 1969,” The Observer (Lehigh Valley Amateur Astronomical Society), January 2019, 12, https://lvaas.org/observer/The_Observer_January_2019.pdf, accessed August 15, 2020.

14 Sandy Mesics, “Paul Shenkle at the Helm in 1969,” The Observer (Lehigh Valley Amateur Astronomical Society), January 2019, 12, https://lvaas.org/observer/The_Observer_January_2019.pdf, accessed August 15, 2020.

15 DAVIDG, online forum posting, Cloudy Nights, January 1, 2014, https://www.cloudynights.com/topic/446639-quantum-telescopes/?p=5786873, accessed August 15, 2020.

16 Rodger Gordon to the author, September 23, 2020.

17 Rodger Gordon to the author, September 23, 2020.