§ 2.2. Photography with the Questar

On This Page

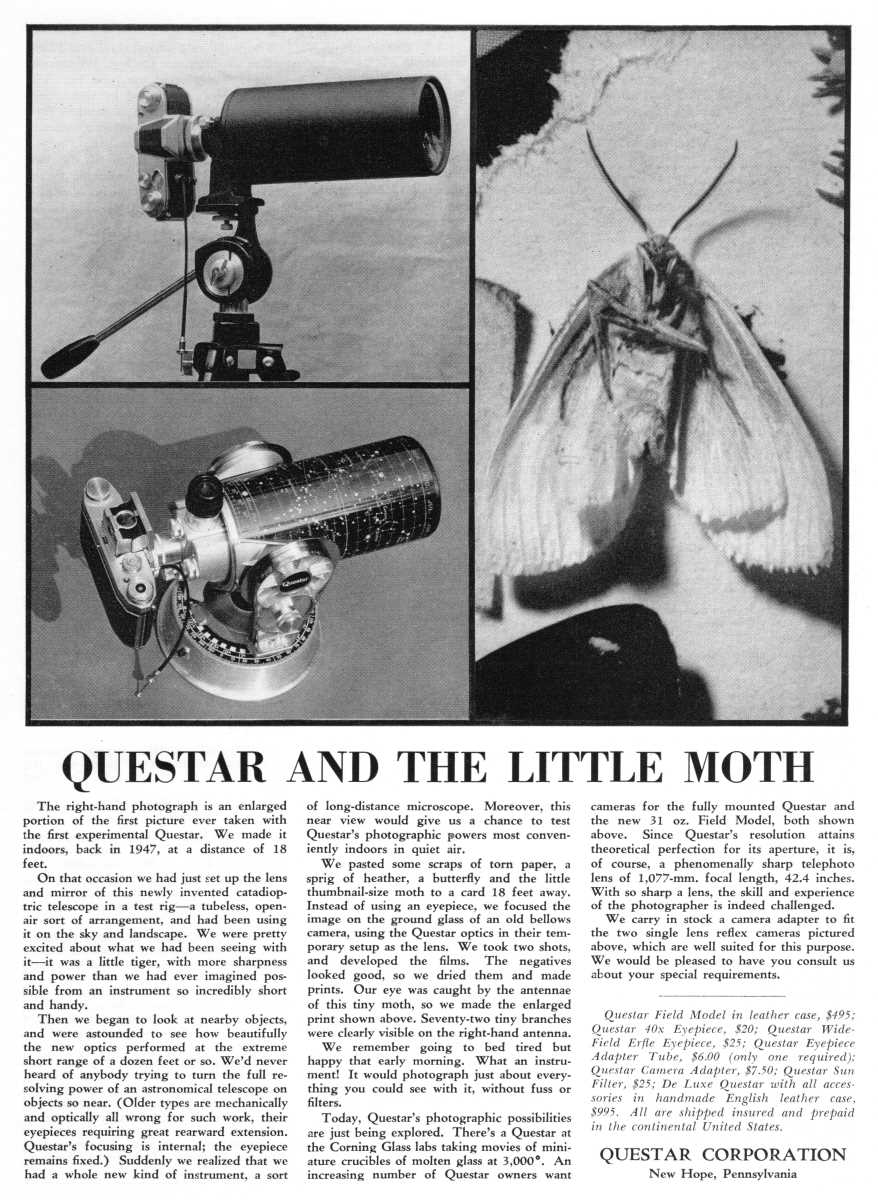

In 1947, Lawrence Braymer and his collaborators had just finished mounting a set of optics for a prototype catadioptric telescope in an open tubeless test rig. After using it to observe both celestial and terrestrial objects, “we were pretty excited about what we had been seeing with it,” he later remembered. “It was a little tiger, with more sharpness and power than we had ever imagined possible from an instrument so incredibly short and handy.”[1]

Next, he thought to use it to examine nearby objects. Such a task would have been impossible for more typical astronomical telescopes, but not so with an instrument that achieved focus by moving its primary mirror. With a camera attached to the test rig, Braymer aimed it at objects he found around him: scraps of torn paper, a butterfly, and a moth. He took two exposures, developed the film, and looked closely at the prints.[2]

His photograph of the moth—the first picture he took with the first experimental Questar—caught his eye. “Seventy-two tiny branches were clearly visible on the right-hand antenna,” he wrote. “We remember going to bed tired but happy that early morning. What an instrument! It would photograph just about everything you could see with it, without fuss or filters.” Nine years later, “Questar’s photographic possibilities are just being explored.”[3]

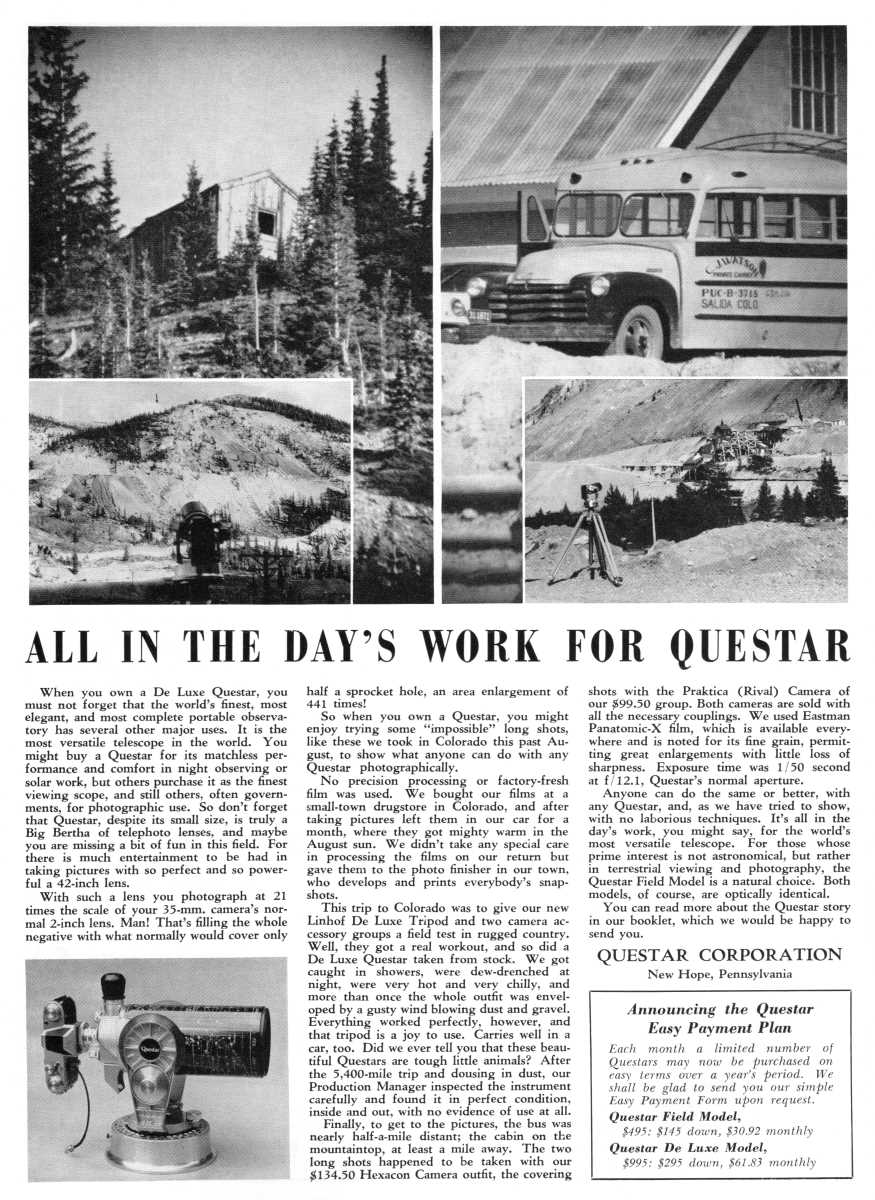

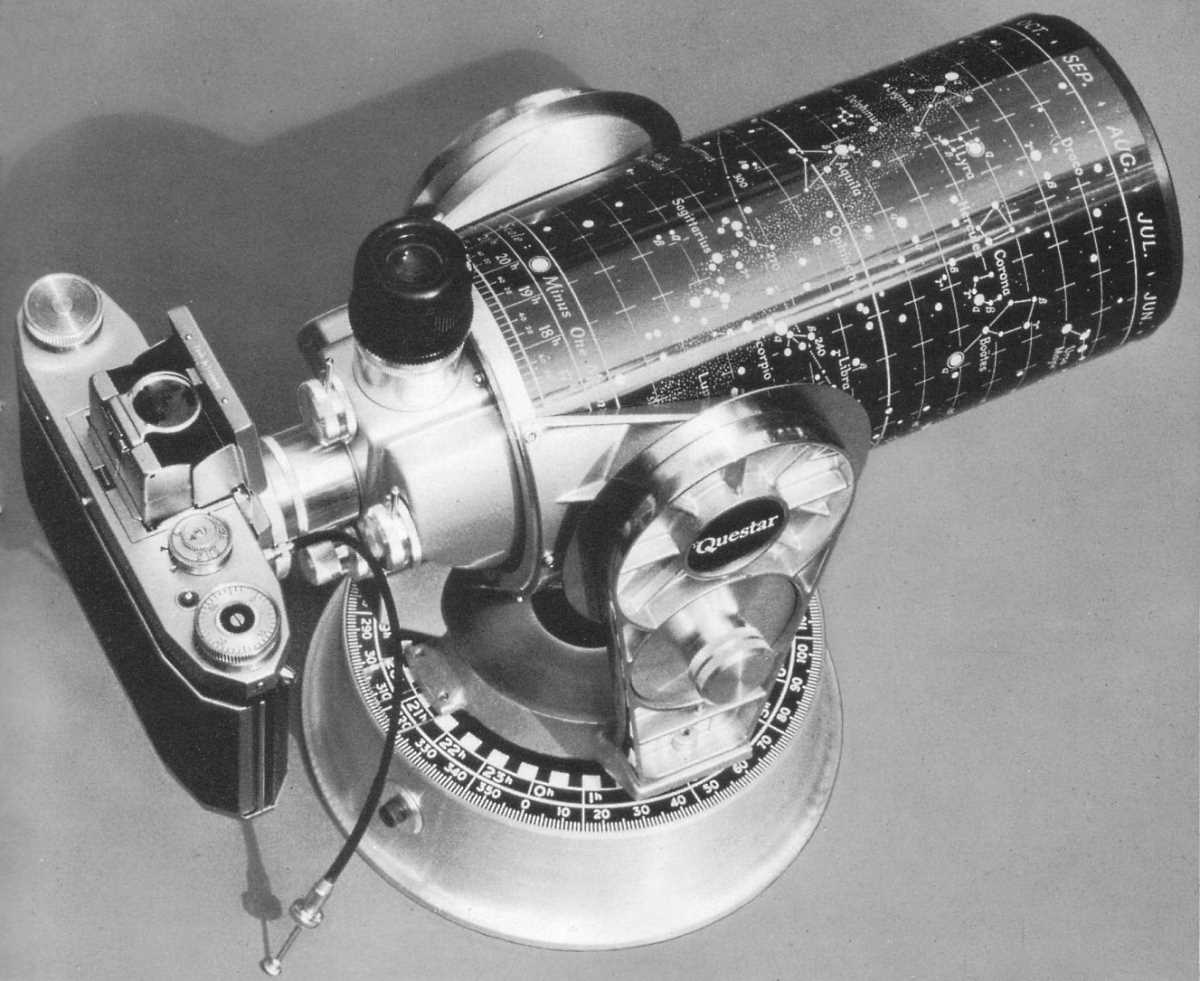

By the time his account appeared in the August 1956 issue of Sky and Telescope, photography had emerged as a topic that Braymer began to explore more deeply in his advertising. That summer, a travel companion joined him in Colorado to perform a series of field tests using a Hexacon camera attached to a Questar to photograph a variety of terrestrial objects. They “purchased Panatomic film in a small Colorado town, exposed it, carried it in our car during a hot August, had it developed and printed back home by our local photo service. No special fresh film, no special treatment, and a month of those high temperatures that cars suffer in summer sun. We wanted to prove that anybody could do good work without special effort.” Using their Hexacon camera’s self-timer to flip the mirror up a half-second before making the exposure, they avoided marring the image that would result from the mechanical jerk of the camera’s normal shutter action.[4]

During that journey, Braymer captured a series of photographs that he and his company would use in advertisements for years. One pair showed a mining operation while another showed an abandoned cabin. Using a perspective-detail technique that appeared in Questar’s advertising time and again, he demonstrated not only the resolving capability of his product but also its usefulness for high-powered photography.

Paging through issues of Sky and Telescope from the mid-1950s, one rarely sees evidence that telescope manufactures put any serious effort into making accommodations for photography. With the Questar, however, Braymer very much thought of it as a central application, one that emerged in his design process even at its earliest stage.

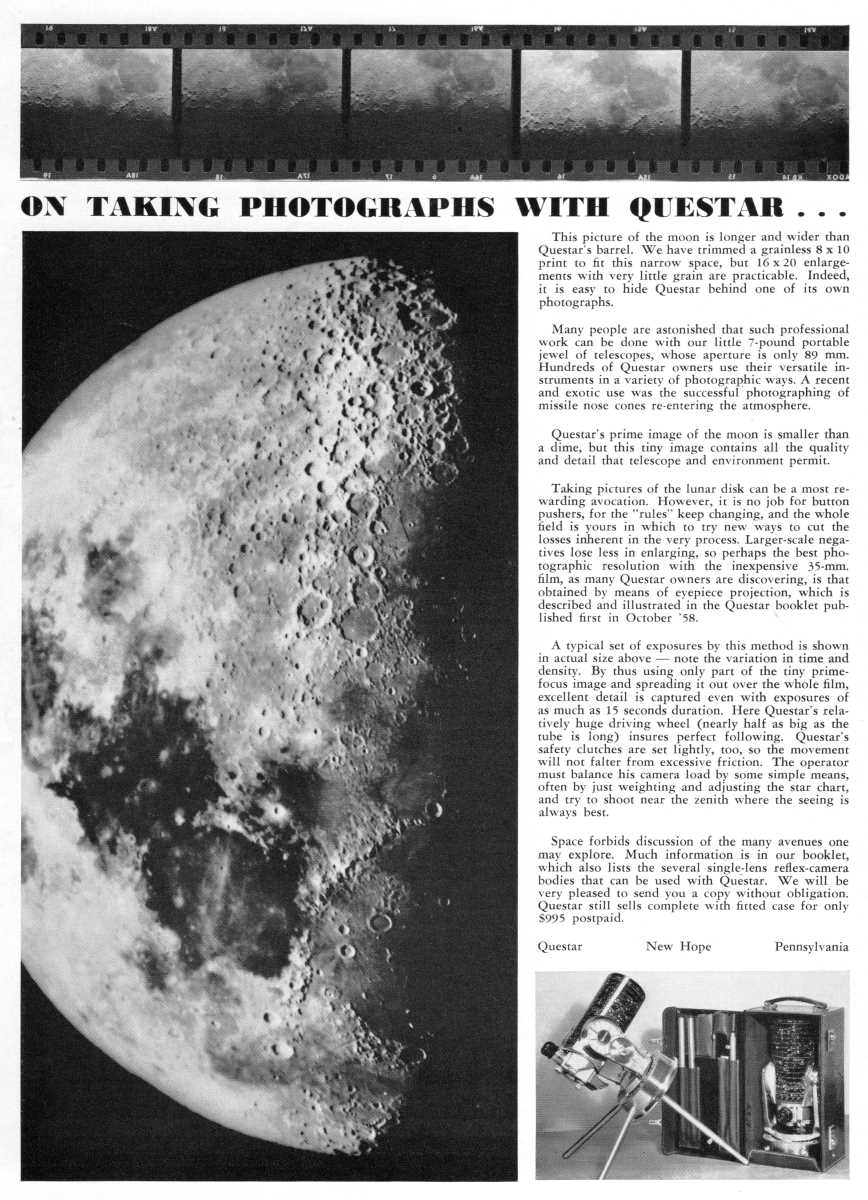

Perhaps other companies did not give telescopic photography much consideration because it was such a special, new, and largely unexplored area. Braymer was fully aware of this reality. In his advertisement that appeared in the December 1959 issue of Sky and Telescope, he wrote that “taking pictures of the lunar disk can be a most rewarding avocation. However, it is no job for button pushers, for the ‘rules’ keep changing, and the whole field is yours in which to try new ways to cut the losses inherent in the very process.”[5]

Braymer continued to offer extensive commentary on photographic techniques with the Questar telescope not only in his magazine advertising but also in editions of the Questar booklet that appeared in the late 1950s and after. And in 1960, he completed a four-page leaflet entitled “Telescopic Photography,” which offered general advice and specific tips on using a Questar for photography. After printing it, he enthusiastically sent it to all of the company’s clients on record.[6] In his leaflet, Braymer wrote:

It seems to us that this pastime combines two arts. Not two sciences, but two arts—the art of taking pictures and the art of correctly using the classical high resolution astronomical telescope. To those who ask where the art enters, let us at once reply that while anyone can push a button or look through a glass, only the fine artist, the skilled worker, can truly wring the utmost out of either enterprise.[7]

By undertaking the challenge, the photographer faced a daunting set of problems.

Impediments to Overcome

Poor Seeing

Even before he undertook the design and development of the Questar telescope, Lawrence Braymer had already expressed a general interest in telescopic photography. In his essay “Wanted: A Tube,” which appeared in the November 1945 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, he commented on the use of cameras with large observatory telescopes. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, astronomers had been moving away from making purely visual observations and were moving instead toward capturing light on photographic plates. The 200-inch telescope at Palomar represented the apex of this trend. Other smaller observatory instruments found new purposes, too. “Telescopes computed for the eye were soon adapted to their new career as cameras.”[8]

But there was a limit to what astronomers could achieve. On one hand, the slight amount of glow that was naturally present in the night sky decreased the contrast in exposures, a problem that was compounded by light pollution from nearby cities. “But the real villain is bad seeing,” Braymer wrote. The air is in motion, and parcels of air with differing temperatures caused the stars to twinkle as the atmosphere bent their light and distorted their appearance. Even during nights with good seeing, the observer only has a fraction of a second to glimpse fine planetary detail before the image blurs again. Foreshadowing his later argument in favor of the small and ultraportable Questar, he wrote that “large telescopes suffer most from poor seeing, since, as size increases, light from one side and light from the other are unequally bent by their differing paths through turbulent air.” But he also conceded that smaller apertures also presented problems. “‘Stopping down’ by diaphragm would only coarsen the image, which is small in proportion as the aperture is large.”[9]

In his 1945 essay, Braymer went on to speculate about electronic solutions that helped compensate for poor seeing, an option that would not have been available to an amateur handling a camera attached to a Questar telescope until much later. Nonetheless, there were other measures for dealing with poor seeing that were within reach.

In his 1960 essay “Telescopic Photography,” Braymer revisited the problem of poor seeing specifically within the context of offering advice to his clients who attempted to take photographs with their telescopes. When using an instrument with long focal lengths of several feet, heat waves become magnified several times more than what we see with the naked eye. Using eyepiece projection to achieve still higher magnifications is possible with the Questar telescope, but photographers will find that using the native focal length of the telescope is usually the best approach. He offered other tips, too. Early morning seeing is typically best. Experiment to find the best time of day for your location. Always keep your line of sight as high above the earth as possible to avoid turbulent mirage waves from marring the image. Avoid photographing over blacktop, dark fields, or black shingled roofs. At night, avoid imaging objects immediately above the horizon. Wait until they are as overhead as possible.[10]

Vibration

Another woe that photographers encountered when they attempted to use their single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras with their Questars was the effect of mirror slap and shutter shock. “Vibration during exposure is our chief enemy,” Braymer wrote. When a user triggers the camera’s shutter, the movement of its internal mechanisms occurred precisely when the photographer made a film exposure. Using a camera attached to a high-magnification instrument like a Questar telescope only made this problem more acute.[11]

Braymer observed that using a camera’s self-timer provided some good results, as mirror slap was dampened a second before exposure. But he got the best results by using a black card in front of the telescope. By keeping the camera’s shutter open, one could quickly move the card away from and back in front of the telescope before closing the shutter. In effect, one’s arms and hands became the shutter mechanism for the camera.[12]

Focus

Achieving sharp focus was still another problem the telescopic photographer encountered. When an instrument was used visually, focusing an image in the eyepiece was usually a straightforward thing. But using a camera’s ground glass to focus an image as sharply as possible was far more difficult. Most “are too coarse-grained to be sufficiently transparent,” Braymer believed. One potential solution was to polish the ground glass with optical rouge in a water paste.[13]

Taking pictures of nearby objects presented other problems. Braymer claimed that the Questar telescope has the ability to form perfect diffraction disks with one narrow ring. Focusing on nearby images causes that disk to leave the central dot and form extra rings around it. Extension tubes offered one potential route toward better resolution as did using a reticule divided into thousandths of an inch to estimate the lineal diameter of Questar’s diffraction disk.[14]

Correct Exposure

The task of determining the correct shutter speed for a given subject added to the challenges the photographer faced. Braymer pointed out that assembling exposure tables, which photographers commonly used in an era before cameras with built-in light meters, was a futile task where high-powered telescopic photography was concerned. It was impossible to anticipate the wide variety of conditions—“the variables of location, sun’s intensity, water vapor, time of year and day”—that varied dramatically from one instance to the next. The main challenge was creating a high-quality negative. “The sharp negative for us is a thin one. We must try to get all the detail possible as thin as possible on the negative, the thin ‘high acutance’ emulsion.” For the finest images, Braymer suggested choosing fine-grain films that achieved thin negatives, films that had become increasingly available by the early 1960s.[15]

He also advised that the photographer should bracket, or make as many exposures as possible. This was the only way to get a perfect picture. Avoid trying to achieve the perfect exposure using reference tables and the like. “Film is cheap. Stick to one film until you get the feel for it.... There is no substitute for taking lots and lots of pictures.”[16]

Equipment

Camera Bodies

In its 1958 booklet, the company identified a number of SLR cameras—Zeiss Ikon’s Contax D and S, the Asahi Pentax, and so on—that could be attached to a Questar telescope. They all furnished three essential attributes: a ground glass focusing screen, a focal plane shutter, and a removable lens whose mount flange could accept a coupler. The Questar essentially became the camera’s lens. Rangefinder camera bodies such as the Leica’s various models could not be used with the Questar without a bulky reflex housing. SLRs that used Compur-style between-the-lens leaf shutters were also unsuitable.[17]

Considering the state of the camera market in the mid- to late 1950s and the fact that rangefinder cameras were at the height of their popularity then, Braymer’s early gravitation to the SLR is remarkable. To be sure, rangefinders, which by this time most often featured a focusing mechanism that was coupled with the rangefinder apparatus itself, were by their very nature incompatible with any kind of non-rangefinder lens without additional and cumbersome adapters. Having the ability to look through the camera’s viewfinder and see what the lens also “saw” was another critical requirement that rangefinders could not satisfy. But during the 1950s, the SLR had yet to find the level of widespread acceptance that it would achieve in the following decade. The fact that Braymer encouraged his customers to consider SLRs at such an early point underscores the degree to which he understood and adopted the latest developments in photographic technology.

Braymer also recognized that most early SLRs on the market had their shortcomings, and he was not shy about offering criticism where he felt it was warranted. He complained that, in all the time since the Ihagee Kamerawerk’s Kine Exakta, the first regularly-produced SLR which was introduced in 1936, manufacturers had been indifferent about building cameras without the whack of the reflex mirror that occurred just before the movement of the shutter curtain delivered another jolt.[18] In spite of this, he still managed to identify a handful of camera bodies that minimized the effect of mirror slap and shutter shock, and he worked with camera technicians to modify a selection of other camera bodies to make them better suited for use with a high-powered instrument like the Questar telescope.

Hexacon

First appearing in Questar’s August 1956 advertisement in Sky and Telescope was one camera body, the Hexacon.[19] A name variant of the Pentacon, which itself was the export derivative of the Zeiss Ikon Contax D of 1952, these later versions found their roots in the groundbreaking Contax S of 1949, the first SLR to feature a pentaprism viewfinder. In the mid- to late 1950s, later models included further refinements. The Contax/Pentacon F of 1956 featured an in-body lens diaphragm release mechanism, bigger reflex mirror, and other improvements. Two years later, the Contax/Pentacon FM implemented a split-image prism rangefinder embedded in the viewscreen. Later models included built-in light meters.[20]

The Hexacon-branded version of the Contax D found a place in Questar’s growing list of camera body offerings. The company listed it for sale at $134.50 beginning in January 1957.[21]

Under its other moniker, the camera appeared in Questar’s marketing as late as September 1960, when Lawrence Braymer wrote that Questar had acquired fifty Pentacon cameras with f/2.8 lenses from a large dealer of photographic equipment. “We are mighty pleased to have these, because they are the very cameras sold beneath the pasted-on nameplate ‘Hexacon.’”[22]

In the same advertisement, Braymer went on to complain about byzantine practices in retail camera pricing, and he added that there was “no use trying to understand today’s mad and senseless camera market.”[23]

As far as ever-shifting product names were concerned, such changes may have stemmed largely from major upheavals in the German camera industry, which had miraculously rebuilt itself after being shattered by World War II and its immediate aftermath. In 1948 after a series of trademark disputes, the East and West German parts of Zeiss Ikon were formally separated into two separate companies: the state-owned Zeiss Ikon VEB of Dresden, East Germany, and Zeiss Ikon AB of Stuttgart, West Germany. As part of the agreement, Zeiss Ikon VEB could no longer use the Contax name and instead adopted Pentacon (a merging of Pentaprism and Contax) for the name of its export version of the Contax D. Further conflict over trademarks ensued until 1958, when Zeiss Ikon VEB was renamed VEB Kinowerke Dresden. In 1959, that company and several others were amalgamated into a single entity called VEB Kamera- und Kinowerke Dresden, which in 1964 became known as VEB Pentacon Dresden. Other reorganizations and name changes occurred in subsequent years.[24]

Praktica

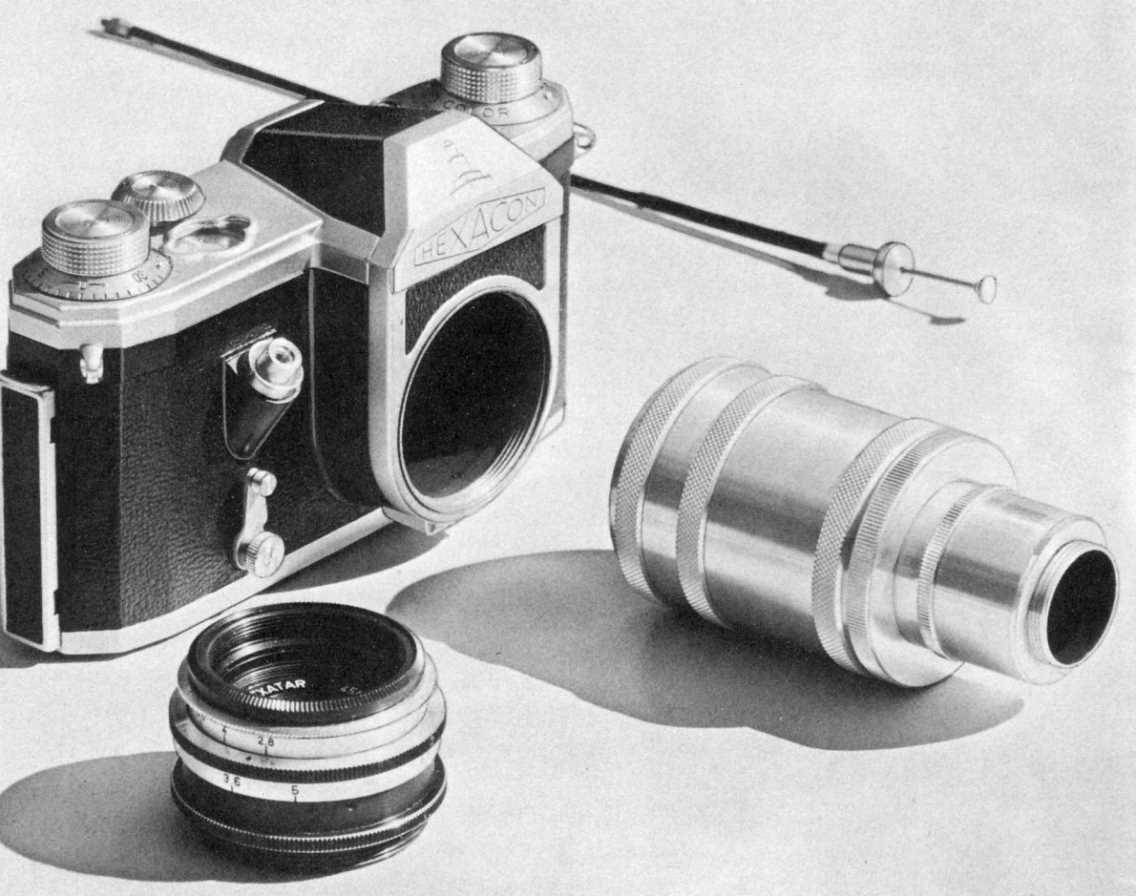

One of the East German companies that found itself placed under the VEB Kamera- und Kinowerke name in 1959 was Kamera Werk (KW) of Niedersedlitz, a suburb of Dresden. The company found its roots in Germany’s early twentieth century camera industry and, like its peers, endured a great deal of adversity around the time of the Second World War.[25] KW manufactured two cameras that caught the attention of Lawrence Braymer.

As early as the May 1956 issue of Sky and Telescope, Questar depicted a Rival Reflex camera, a rebranded import of the Praktica FX, attached to a Questar telescope.[26] Introduced in its original form in 1949, when KW had been known as Kamera-Werkstaetten, the Praktica featured an M42 x 1mm screw-in lens mount and a built-in waist-level finder with magnifying glass.[27]

Questar began offering the Praktica for $99.50 in its January 1957 advertisement in Sky and Telescope.[28] But its longevity in the company’s stable of products was short lived. A small rendering of a well-used marketing image depicting a Praktica camera body attached to a Questar made its last appearance in company advertising in the July 1962 issue of Sky and Telescope.[29] In all likelihood, Questar had already stopped offering it well before then.

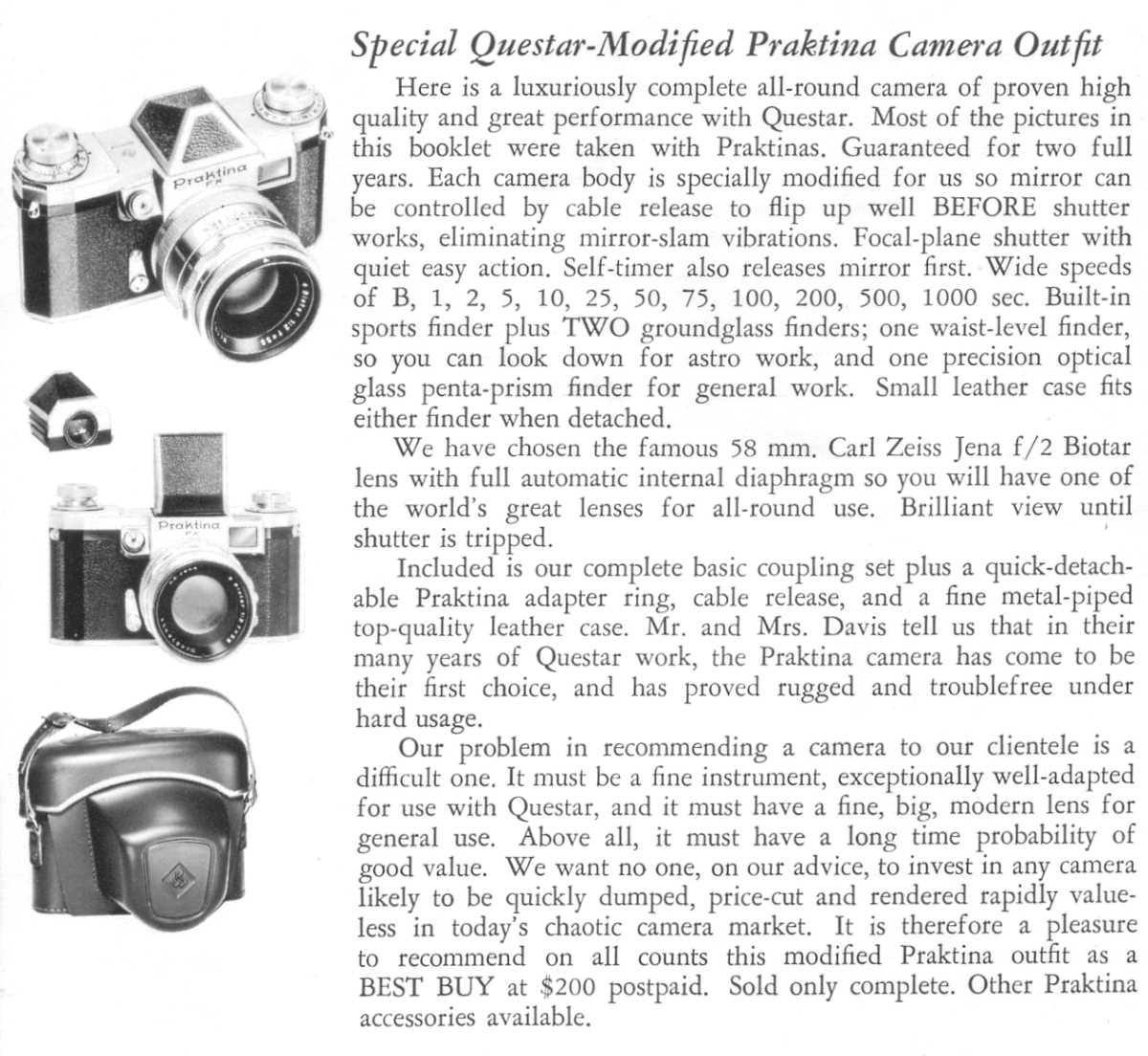

Praktina

In 1952, KW introduced what later became another of Questar’s brief but perhaps more significant camera body offerings: the Praktina. Similar in certain superficial respects to the much simpler Praktica, the more professionally-oriented Praktina featured a unique and robust breech-lock lens mount, a semi-automatic stop-down lens aperture, and a number of interchangeable viewfinders, ground glass focusing screens, and other accessories.[30] As camera enthusiast Mike Eckman writes, the Praktina was the first “system” SLR camera. Eckman argues that other manufacturers like Nikon and Canon drew from the Praktina when they designed their own premium lines later in the 1950s.[31]

The Praktina FX, an improved model that appeared about a year after the original version,[32] enjoyed a place in Questar’s offerings for only a few years during the late 1950s or early 1960s. In its November 1960 booklet, the only place the Praktina made an appearance in Questar’s marketing literature, the company wrote that “each camera body is specially modified for us so [the] mirror can be controlled by cable release to flip up well BEFORE shutter works, eliminating mirror-slam vibrations.” The camera’s self-timer also released the mirror before its shutter curtains swept from side to side to make an exposure. Questar included Carl Zeiss Jena’s famed 58mm f/2 Biotar lens, a basic coupling set, a Praktina adapter ring, a cable release, and a leather case, all for $200.[33]

That amount was significantly lower than Standard Camera Corporation’s advertised list price of $297.50 for an equivalent regular production camera body and f/2 Biotar lens in 1957 and 1958. But Standard’s price for that very same package had dropped to $149.50 by the time Questar marketed its specially modified Praktina FX in November 1960.[34] Other retailers would further slash their price for the Praktina in the months ahead.

The Praktina FX appears to have been the first Questar-modified camera body that the company sold. But the short-lived nature of that offering matched the fortunes of the Praktina as a whole. Even though KW announced a slightly improved Praktina IIA in 1955 and began producing it three years later, it would take another three years for the updated model to become available in the United States. Even before that point, though, it had become clear that the more refined IIA would never attract many buyers to the Praktina. By the time American buyers could finally access the improved model on the domestic market in 1961, KW had already discontinued production of the entire line in May 1960.[35]

As the Praktina faded into obscurity, another camera from the other side of the world quickly surpassed it. The new entry outmatched all the others, too.

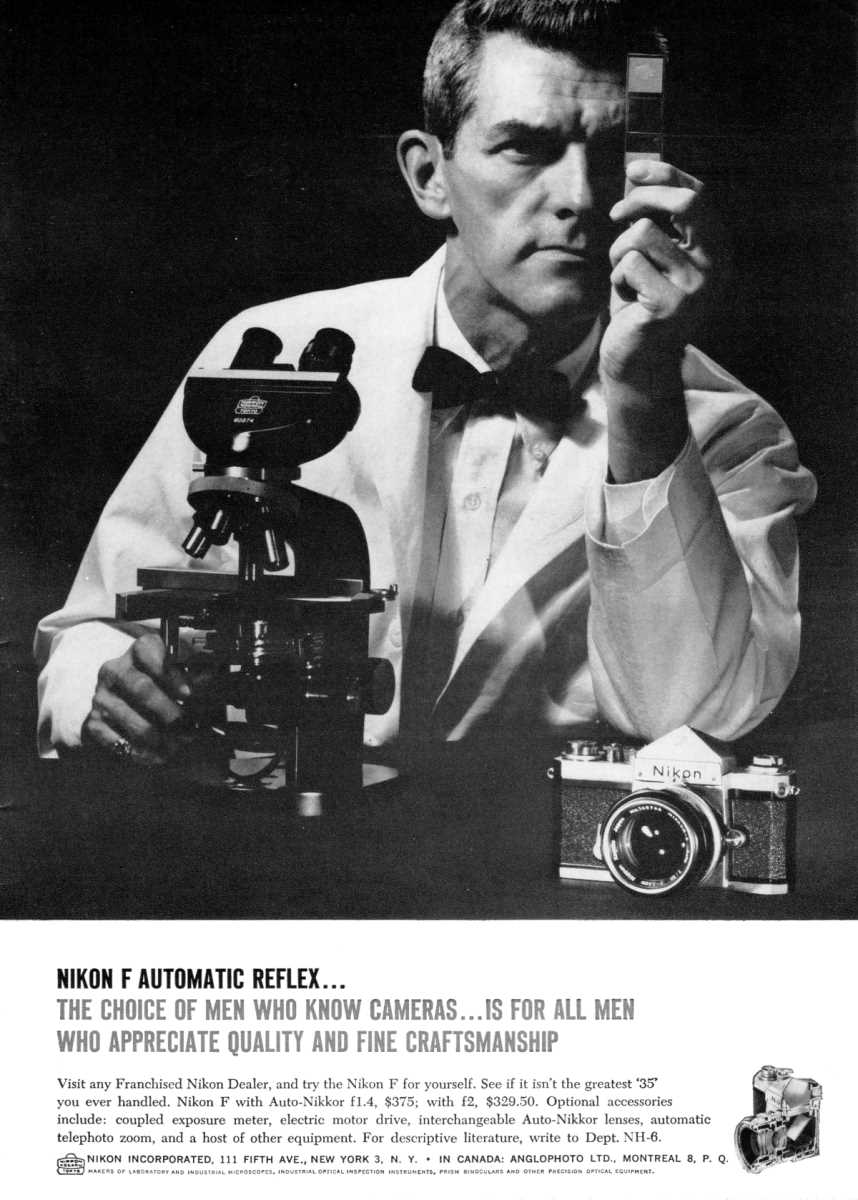

Nikon F

Eclipsing the trailblazing Praktina and marking the rise of the Japanese camera industry over German competitors overall, the Nikon F took the photographic world by storm. Mirroring its general market success, it became the most prominent camera by far in Questar’s early product offerings.

Introduced in April 1959 by Nippon Kogaku, K.K. (Japan Optical Company),[36] the Nikon F took design cues from a number of earlier SLRs like the Praktina.[37] But this milestone camera was a far more clever and dependable gadget—the prominent New York camera repairman Marty Forscher famously called it a hockey puck—and its commercial success during the 1960s was completely unsurpassed.

The Nikon F broke new ground as the first truly modern SLR. Its multitude of advanced features—lenses with fully automatic aperture diaphragms, an instant-return reflex mirror, a single shutter speed dial, and a modular “system” construction that accommodated a vast and ever-expanding universe of accessories—had all appeared earlier in other cameras but never together in a single model.[38] Perhaps above all else, the Nikon F did more than any other camera to show photographers the advantages of the SLR design and to end the age of the rangefinder.

Ever attuned to the latest developments in the camera industry, Lawrence Braymer did not take long to notice the Nikon F and bring it into the fold. Using the same September 1960 advertisement in which he noted Questar’s acquisition of fifty Pentacon cameras, Braymer also noted that his company had become an authorized dealer of Nikon equipment, which “seems to be, in our considered opinion, the best obtainable.” The Nikon F, he continued to say, has the least shutter recoil, and the shutter can be operated with the mirror locked up. It was not cheap: sellers including Questar sold the Nikon F for between $220 (camera body alone) to $375 (body with 50mm f/1.4 lens), prices that were roughly a quarter to a third of what an entire new Standard Questar cost. Yet Braymer did not hesitate to sing its praises. “Every Nikon product is so beautifully made that you sense its quality at first glance.”[39]

At least for photographers who wished to use the Nikon F with their Questars, the mirror lock-up feature that Braymer noted had its shortcomings. In order to move the reflex mirror into its upward position and allow the assembly to settle down before making an exposure, one had to turn the mirror locking knob next to the lens mount and then fire the shutter. This indeed moved and locked the mirror up, but it did so immediately before making an exposure, causing the type of image-blurring vibrations one sought to avoid while the film was being exposed at least for one frame. Using the standard lock-up mechanism effectively forced one to waste an exposure, in other words.[40]

Another problem existed. After the mirror had been flipped up, it stayed there and blocked the camera’s viewfinder, making it impossible to recompose the next photograph or refocus if necessary. To use the viewfinder again, the user was forced to disengage the locking mechanism, return the mirror to its downward position, recompose or refocus, and begin the whole exposure-wasting process over again.

In May 1963, the company announced that it had taken an additional step to solve these problems. “May we tell you about the first wholly satisfactory camera body for use with Questar? It is a special Questar-modified Nikon F, obtainable only from us.”[41]

It seemed to solve all of the problems that Braymer had outlined in his past writing. “For the first time,” the company wrote in a February 1964 advertisement, “Questar has a true photographic model, and a camera without mirror slap, shutter vibration, or too-dim focusing.”[42]

The modification was relatively simple. By depressing a small added button not found on normal production Nikon F camera bodies, the photographer could release the reflex mirror and allow the entire assembly to settle down before pressing the shutter button. After making the exposure, the mirror would then return to its original position.[43] The Questar modification, in other words, completely separated the reflex mirror flip-up action from the shutter mechanism. The photographer was free to use the viewfinder as necessary and could flip the mirror up without having to operate the shutter and waste an exposure in the process.

Precisely who added this mirror release button to Nikon F camera bodies for Questar is unclear. On his extensive website detailing the Nikon F, Richard de Stoutz writes that the modification was made either by Questar or for the company by Ehrenreich Photo-Optical Industries (EPOI),[44] Nippon Kogaku’s exclusive importer in the United States at the time.[45] Nikon collector Matthew Lin speculates that Nippon Kogaku itself performed the modification for Questar.[46] And in his discussion of Nikon F variants, Stephen Gandy writes that Nikon implemented the additional button on most examples with perhaps Questar doing so on others.[47]

Over the camera’s long production run, Nikon made its own design refinements to the Nikon F. The most conspicuous changes added light metering to the camera. Upon introducing the camera to the market in 1959, Nikon offered a relatively simple clip-on selenium light meter that coupled with both the camera’s shutter speed dial and the lens aperture ring. But that accessory served only a temporary role while Nikon worked to incorporate more recent advances in light metering technology into the Nikon F system. In 1962, Nikon introduced the first Photomic viewfinder, which featured a cadmium sulfide (CdS) light metering photocell that was independent of the camera’s main light path. In 1965, the Photomic T appeared. It integrated through-the-lens (TTL) whole-field light metering with far more accurate readings than what an independent photocell could provide. In 1967, the Photomic Tn implemented a refined 60/40 center-weighted metering pattern that Nikon used for decades. And in 1968, Nikon began offering the Photomic FTn, which simplified the process of coupling the lens aperture to the meter, among other improvements.[48]

Questar adjusted its custom-modified Nikon F camera body offerings to keep up with developments. In its April 1966 price catalog, the company made the Photomic T viewfinder and its integrated light meter available to its customers. In addition to selling it as part of a complete camera package, Questar offered a service for converting older Nikon F bodies to accept the new viewfinder.[49] Later, Questar added the Photomic FTn viewfinder to its October 1968 price catalog.[50]

The beginning of the end for the Nikon F came with the introduction of the F2 in 1971. For a few years, Nikon produced both models concurrently. Notably, the missing feature that made the Questar-specific modification necessary—a mirror lock-up feature that operated independently from the shutter mechanism—became a standard feature on the newer model.[51] Nikon had mostly caught up with what Lawrence Braymer had been looking for in a camera body.

When the Nikon F’s fourteen-year production run finally ended in October 1973, Nikon had produced around 862,600 units.[52] But Questar-modified versions continued to be available for years thereafter. Perhaps because it had ample stock of its custom-modified camera bodies to work through, Questar marketed its special Nikon F as late as 1978.[53] The company never included the F2 in its product listings.

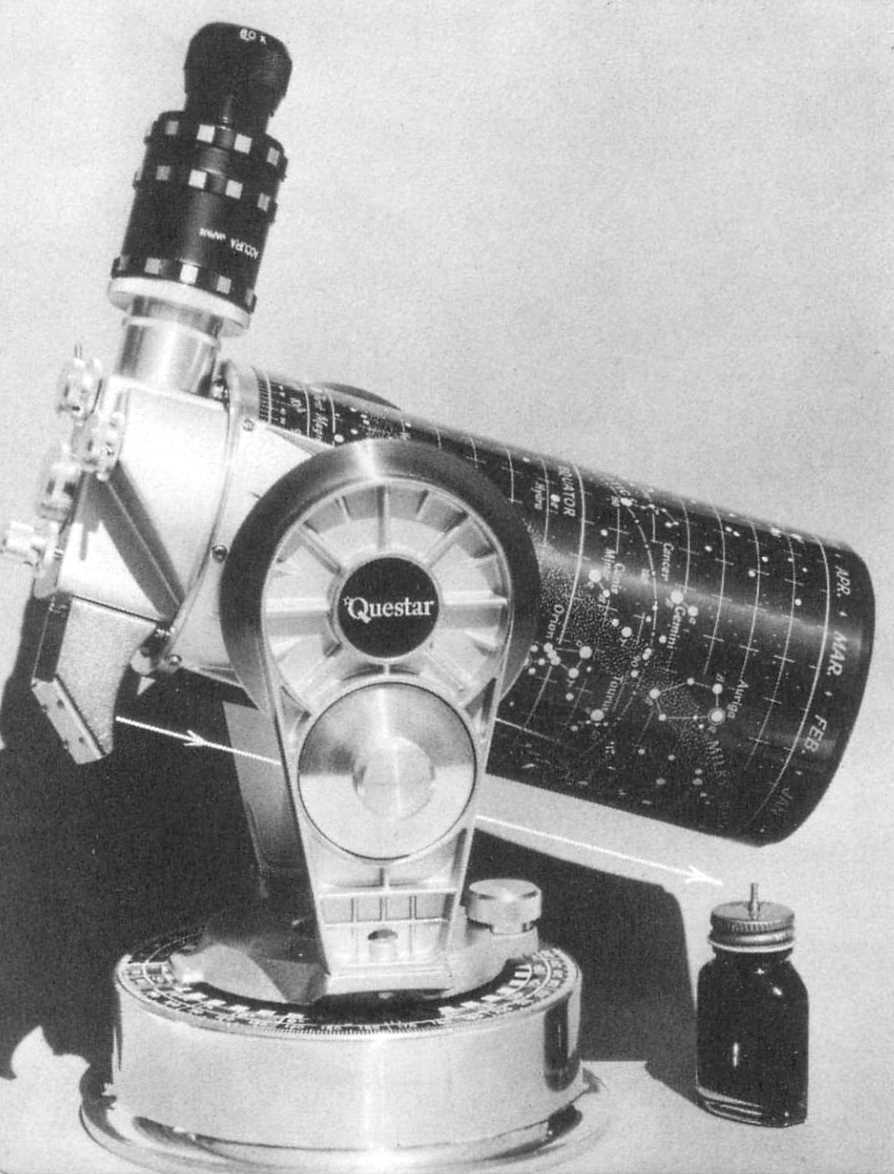

Camera Couplings

For attaching a camera to the Questar telescope, the company in its early years offered a basic coupler set. It consisted of two simple pieces. First, an additional eyepiece adapter tube with 0.925 male threads on one side and 1-3/16 x 32 female threads on the other side connected to the axial port’s 0.925 female threads on the instrument’s control box. Second, an additional adapter with 1-3/16 x 32 male threads on one side and Praktica/M42 male threads on the other side functioned as the contact point for the camera body. If one’s lens mount did not have the proper threads, an additional adapter was necessary.

During the first two years of Questar’s production, the company’s promotional literature spoke only in general terms about photographic applications. “Not only will Questar photograph everything that can be seen through it,” the company wrote in its 1954 booklet, “but it will do so in a variety of ways.” No additional filters, lenses, cradles, mountings, or focusing jackets were required. The “addition of merely a ground glass, filmholder and shutter, makes Questar a complete telephoto camera.”[54] But it included no specific indication of any camera coupler accessory that the company may have made available at that time, and it made no reference to the manner in which a camera body attached to a Questar.

The earliest indication that a camera coupler was available is a document dated April 1956 which depicts a Praktica/Pentacon camera adapter.[55] This suggests that the camera coupler made its first appearance around this time. If this is true—and the sudden proliferation of photography-related content in Questar’s magazine advertising beginning in the middle of 1956 seems to confirm this—the company waited nearly two years after production of the Standard Questar began to make a proper camera coupler available to its customers.

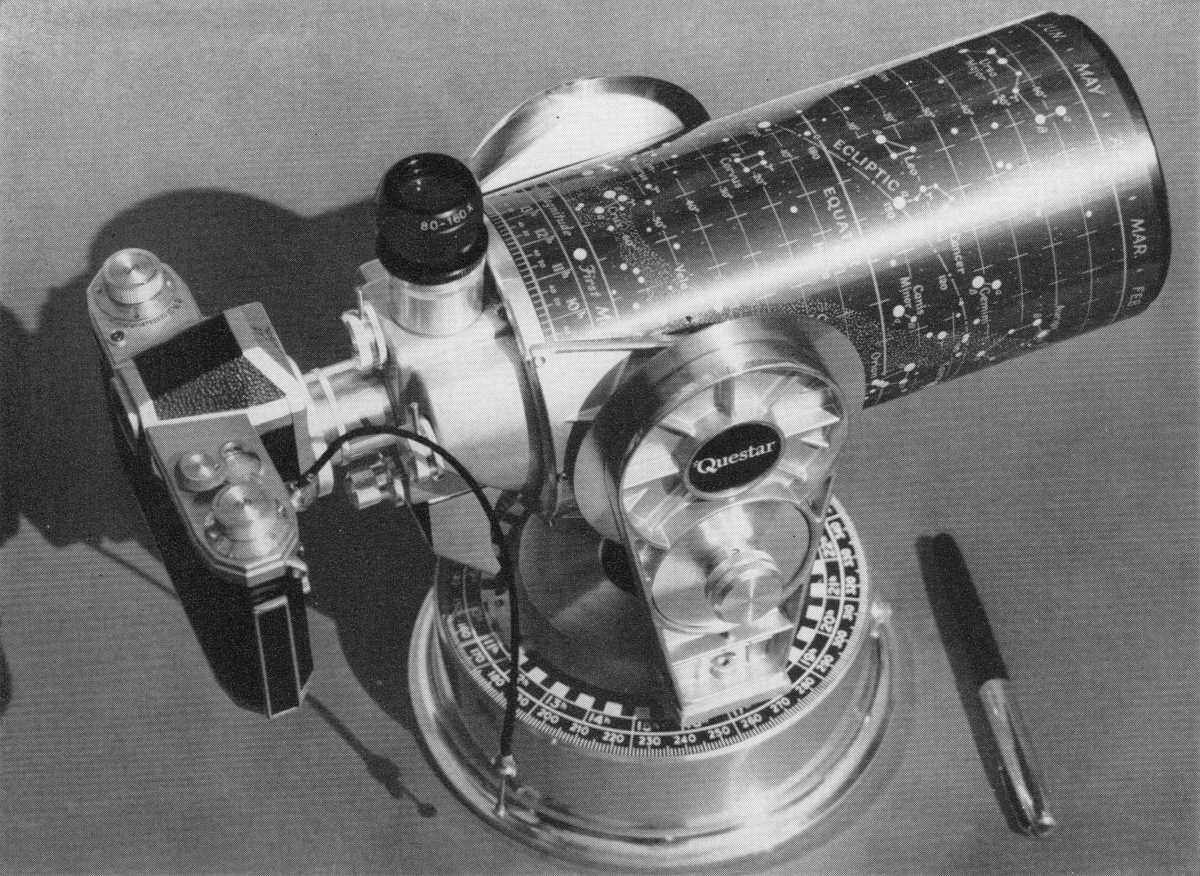

Extension Tubes

A photographer could opt to attach a camera closely with the telescope, resulting in a focal length of about 49 inches at f/14. Alternatively, one or more extension tubes with M42 threads could be employed for increasing the photographic focal length of the instrument 56 inches at f/16. “An important feature of this variable focusing,” as the 1958 Questar booklet pointed out, “is that it permits Questar to retain its very perfect correction at all distances.”[56]

Any extension tube set with M42 threads would have been suitable for this purpose. Questar offered an Accura-branded three-piece set that was manufactured in Japan. During its early years, the company depicted two types: one with a silver finish and knurled edges that appeared in the October 1958 Questar booklet and another with a black finish and silver squares as depicted in the November 1960 booklet.[57] When the company undertook the manufacture of its own extension tubes years later, it maintained the appearance of the latter.

When used with an eyepiece ring that clamped between any two pieces of the extension tube set as supplied by Questar, one could also increase the effective focal length of the telescope for higher-magnification visual observing. This eyepiece ring, as Questar indicated in its November 1960 booklet, was “held between uppermost tube sections to lift [the] 80-160x eyepiece up to 2 more inches above the built-in amplifying lens for powers to about 300x. No need to buy expensive extra high-power eyepieces with tiny lenses, small fields and uncomfortably low eyepoints. This is the modern way to achieve high powers with a superb wide-field ocular of comfortable normal size. By changing sections to vary height you may choose your favorite degree of magnification.”[58]

Questar noted a third function of the extension tubes: eyepiece projection photography. With the eyepiece ring between the camera adapter and first tube, one could use the 80-160x eyepiece to project an image “64 mm. to film for full coverage of double frame at effective focal length of 17 feet.”[59]

In an addenda section of June and September 1959 editions of the October 1958 Questar booklet, the company noted still another function for the extension tube set, albeit one that would not have been completely obvious to most users. With the 80-160x eyepiece positioned on top of the full set of three tubes, a Questar owner could also use the finder system as a long-distance microscope. “No need for expensive photographic objectives and elaborate equipment. Only a standard coupling set is used to elevate [the] eyepiece—distance and power are determined by its height.”[60] This option presented the user with a novel and unique way to use one’s instrument indoors to explore a variety of objects under high magnification.

The Photography of Dorothy and Ralph Davis

With their cameras connected to their telescopes, Questar’s clients undoubted made good use of their equipment. But one particular couple stood out. Not long after they purchased their instrument, Dorothy and Ralph Davis emerged as especially prolific photographers who used their Questar telescope to image a variety of subjects. Their work regularly appeared in the company’s advertising over the course of decades.

Earlier in her life, Dorothy was named Doris Alice Mays before she married Ralph. Her friends sometimes used her nickname Dot. In 1943, she trained with the Women Airforce Service Pilots in class 43-8 at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas. While male pilots served in combat during World War II, WASP trained female pilots who later took on jobs that included testing and ferrying aircraft. Many became pilot instructors themselves. Settling in Florida with her husband after the war, Dorothy became active with the Sarasota Historical Society. Meanwhile, Ralph worked for the Sarasota County Engineering Department. The couple eventually moved into a house on Little Sarasota Bay. Their street would later be named Questar Lane.[61] In his capacity as a public employee, Ralph, who was in his late 30s by the mid-1950s and who sometimes went by the nickname Bud,[62] perhaps had enough influence with local authorities to persuade them to name the street he and his wife lived on after their favorite telescope.

Dorothy and Ralph eventually developed an enduring interest in using their Questar telescope for photography. With their hard-working Hexacon and Praktina cameras attached to their Questar,[63] the Davises first tried their hand at lunar imaging. Having acquired their Questar around April 1956,[64] Dorothy and Ralph began as “absolute novices” later that year in December. Their advancement was quick.[65]

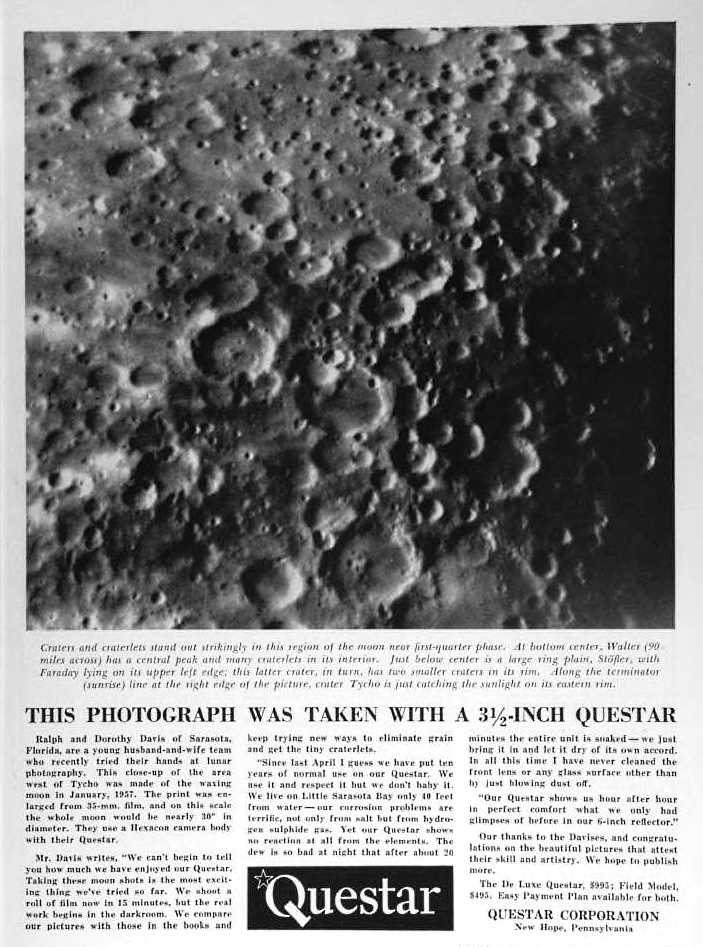

The Davises’ photography first appeared in a Questar advertisement in the March 1957 issue of Sky and Telescope. It was also the first occasion that the company had used its magazine advertising to feature a photograph of any astronomical object taken with a camera attached to a Questar telescope. The image was a close-up view of the lunar region to the west of Tycho as it appeared three months before in January.[66]

Ralph spoke for himself and Dorothy when he wrote that, in less than a year of use, they had put a decade of wear and tear on their Questar. “We use it and respect it but we don’t baby it.” Even in the extreme moisture and corrosive sea salts in the Florida air, Dorothy and Ralph were not shy about putting their instrument through its paces. He also commented on the way in which their darkroom technique had matured. For their part, Questar congratulated them on “their skill and artistry,” and the company hoped to publish more of their images.[67]

In the following months and years, Questar published many more. The company included numerous photographs of the lunar surface by the Davises in advertisements that appeared in Sky and Telescope and other publications throughout the rest of the 1950s and beyond.

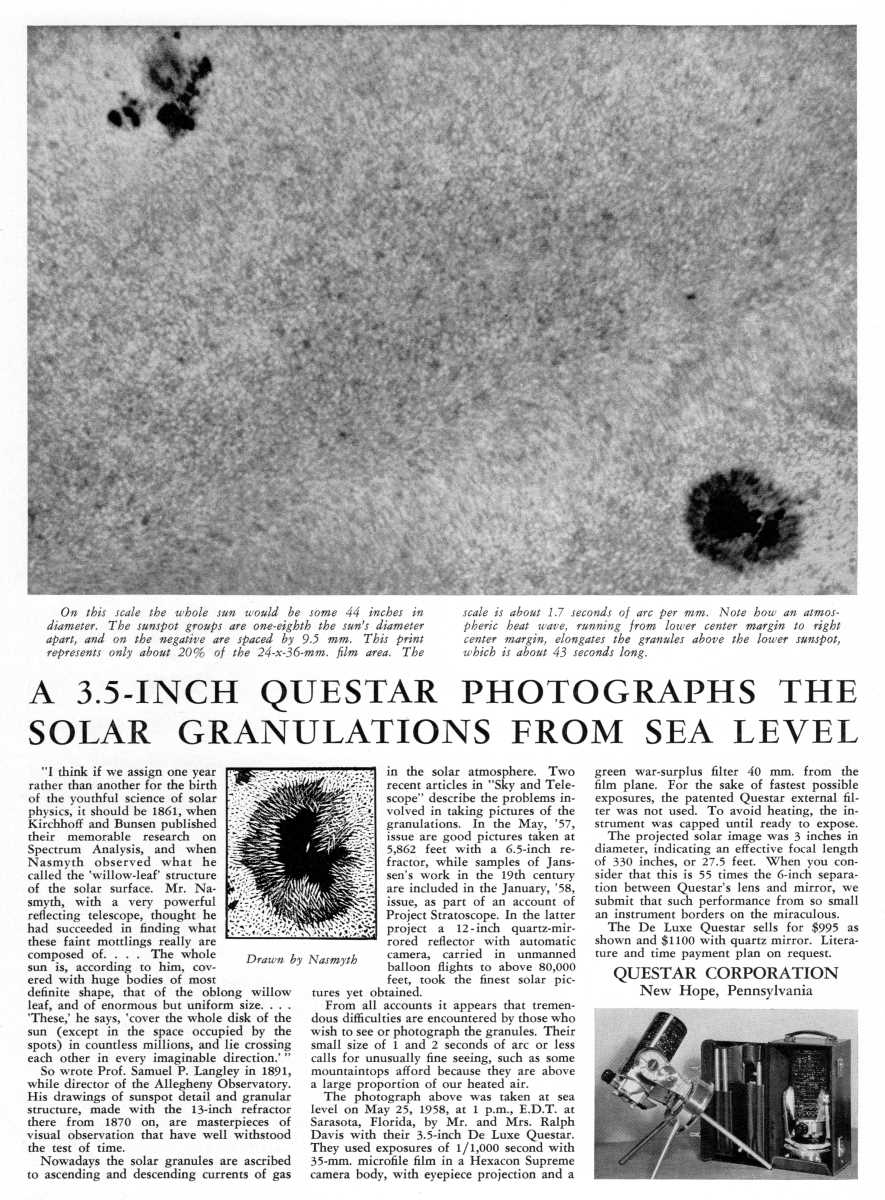

Dorothy and Ralph did not limit their repertoire to the Moon. In the August 1958 issue of Sky and Telescope, the company featured a remarkably well-resolved image of solar granulation by the Davises. The image was part of the first advertisement that Questar specifically dedicated to solar observing. With their Hexacon camera and a green filter near the focal plane, the Davises captured the photograph in May 1958 near their home in Sarasota. They used a technique that some might rightfully characterize as recklessly dangerous. “For the sake of fastest possible exposures, the patented Questar external filter was not used. To avoid heating, the instrument was capped until ready to expose.” Setting aside the risks involved with this technique, Questar considered the superb quality of the image that resulted from it. “We submit that such performance from so small an instrument borders on the miraculous.”[68] The company reproduced many other images by the Davises of sunspots and photospheric granulation in subsequent advertisements.

Questar sometimes offered additional comments on their technique. “It is probably Ralph Davis’ care in balancing and focusing his Questar that secures such superb negatives with only 3.5 inches of aperture, while Dorothy Davis will stick to a good negative in the darkroom for hours, making print after print until the right one comes just so,” the company admiringly wrote about their method.[69]

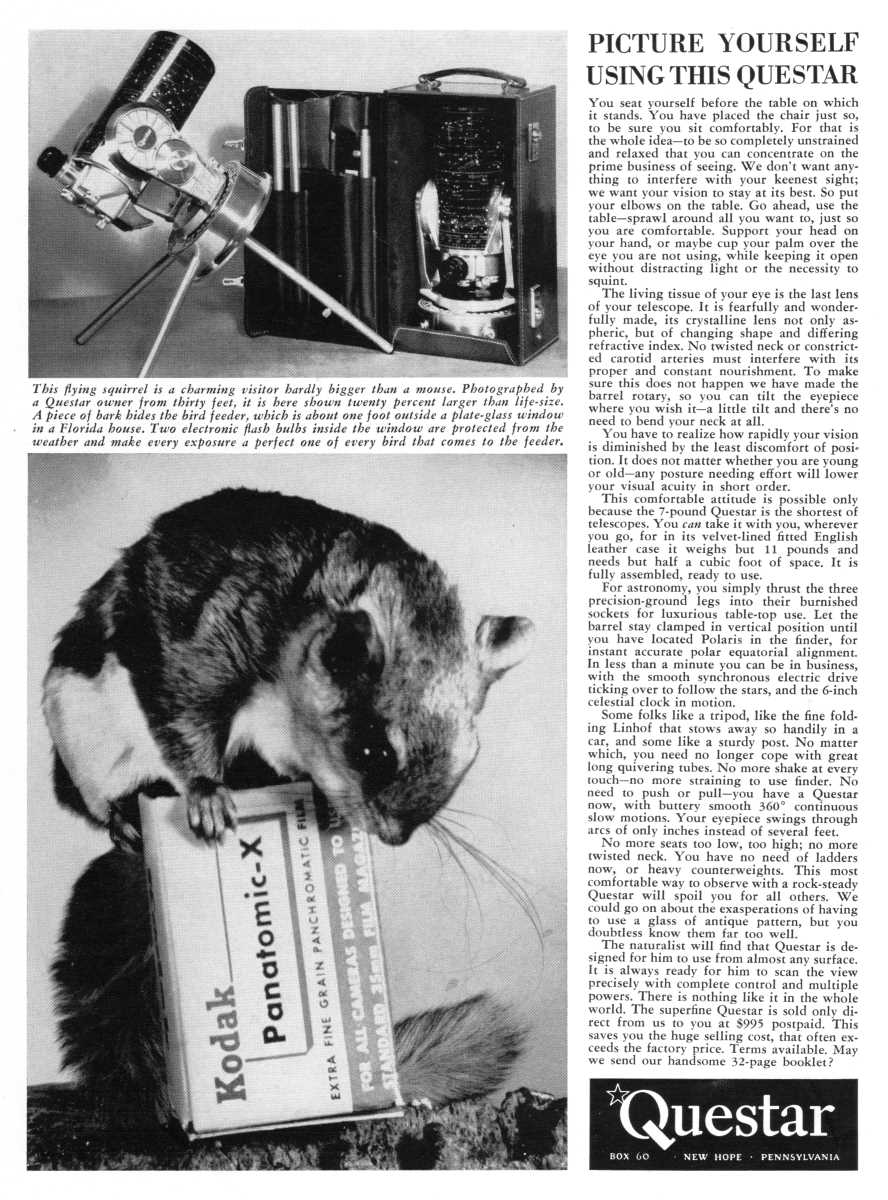

In addition to photographing the Moon, the Sun, and the planets, the Davises also imaged a wide variety of terrestrial and nature objects during the day. In the August-September 1960 issue of Natural History magazine, for instance, Questar featured a picture that Dorothy Davis captured of a flying squirrel perched on the packaging for a roll of Kodak Panatomic-X film.[70] It was an appropriate tribute to the photographic ability of the Questar telescope to record what one could see at the eyepiece.

In its advertising, the company often featured images that Questar owners like the Davises sent in. Magazines themselves took notice, too.

Questar’s Relationship with Modern Photography Magazine

Modern Photography dedicated its August 1962 issue to telephoto lenses of all kinds. As part of its coverage, the magazine’s publishers ran a photograph that Dorothy and Ralph Davis took with their Questar of a screech owl, an image that had first appeared in Questar’s magazine advertising earlier that year.[71]

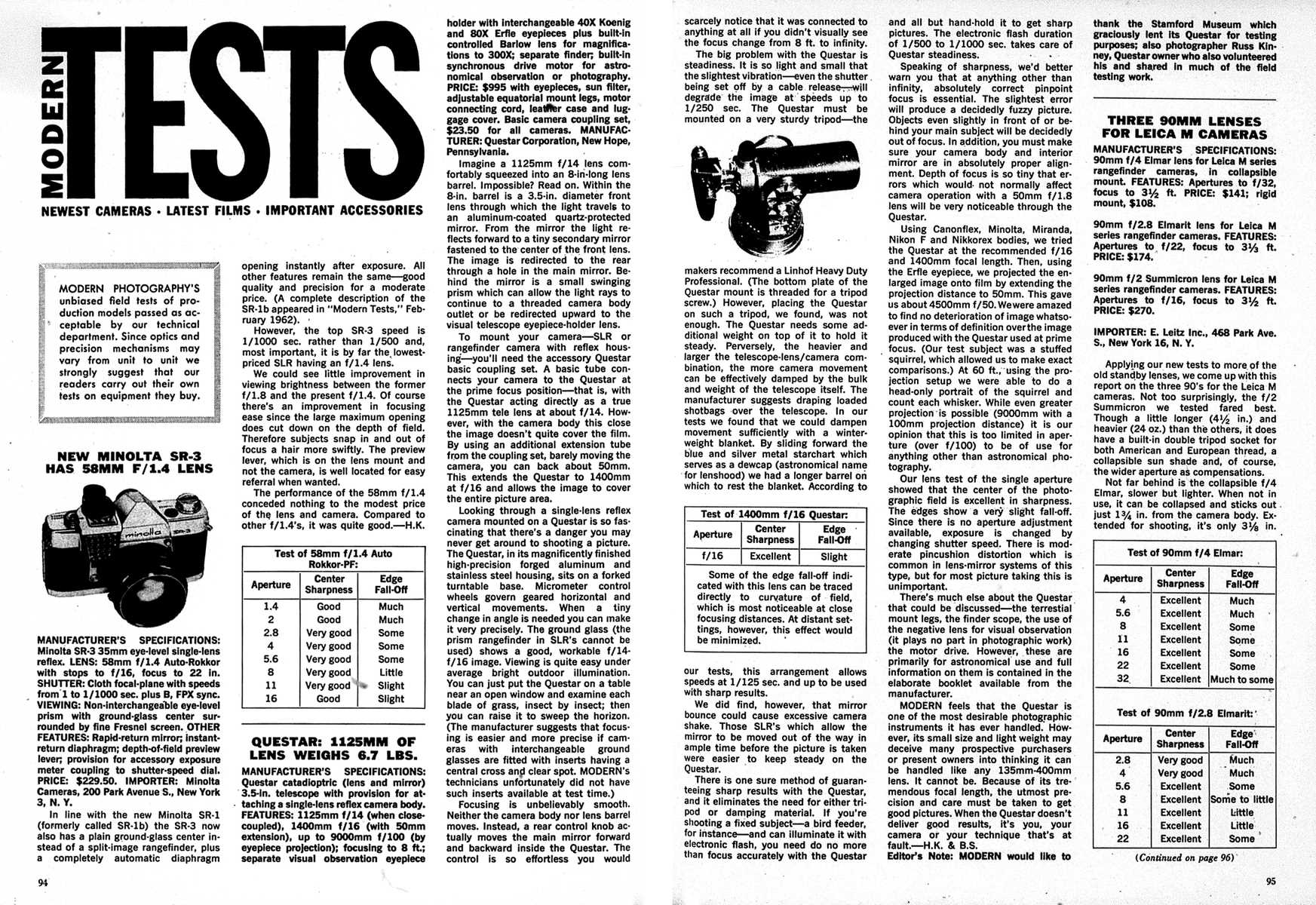

In the same issue, Modern Photography also published a report on the Standard Questar. Widely known for offering in-depth reviews of photography equipment in its monthly “Modern Tests” column, the publication gave the Questar the same highly practical field trials it applied to all the other gear it covered. In their writeup on the Questar telescope, Herbert Keppler and Bennett Sherman considered the instrument specifically in terms of how a photographer could use it as a long telephoto lens.

Keppler and Sherman began their article with a mental challenge: “Imagine a 1125mm f/14 lens comfortably squeezed into an 8-in-long lens barrel. Impossible? Read on.” After describing the Questar’s basic features and operation, they continued with a glowing evaluation. “Looking through a single-lens reflex camera mounted on a Questar is so fascinating that there’s a danger you may never get around to shooting a picture.” With the benefit of bright outdoor light, they wrote, one could use the instrument to survey objects in one’s surroundings no matter how minute and with incredible detail.[72]

The biggest problem with the Questar telescope, Keppler and Sherman admitted, “is steadiness.” Here, they echoed Lawrence Braymer’s own refrain not only about the effects of mirror slap and shutter shock on image sharpness but also about the importance of finding a camera that offered its user the ability to move the mirror out of the way prior to firing the shutter.[73]

Amplifying Braymer’s own warnings about the importance of focus, Keppler and Sherman stressed that “absolutely correct pinpoint focus is essential.” Noting the shallow depth of focus, they continued to say that “the slightest error will produce a decidedly fuzzy picture.” Alignment between camera body and internal reflex mirror was of critical importance. “Depth of focus is so tiny that errors which would not normally affect camera operation with a 50mm f/1.8 lens will be very noticeable through the Questar.”[74]

Having used a variety of camera bodies with their test Questar at prime focus, they “were amazed to find no deterioration of image whatsoever in terms of definition.” Using the higher-powered Erfle for eyepiece projection, they “were able to do a head-only portrait of [a] squirrel and count each whisker.”[75]

Speaking on behalf of the magazine, Keppler and Sherman left no doubt about their feelings. “Modern feels that the Questar is one of the most desirable photographic instruments it has ever handled.” Do not be fooled, they warned. The instrument could not be handled like any other more typical telephoto lens. “Because of its tremendous focal length, the utmost precision and care must be taken to get good pictures. When the Questar doesn’t deliver good results, it’s you, your camera or your technique that’s at fault.”[76]

More than three years after Modern Photography’s 1962 report appeared, Herbert Keppler remembered the lead-up to it. After requesting a test Questar and even offering to rent it, he and his colleagues “received a curt note thanking us for our interest with an explanation that Questars were never loaned for test reports since Questar was not interested in such publicity, did not wish to sell to photographers, and Questars weren’t available for rent either. Would we do Questar a favor and not mention it at all?”[77]

Undeterred, the writers at Modern Photography instead engaged with Stamford Museum, who owned a Questar and was willing to loan it to them. Photographer Russ Kinney also volunteered his own Questar and contributed his time to the kind of field test that Questar and presumably Lawrence Braymer himself did not wish them to do.[78]

After finishing their report, Keppler and his co-writers sent it to Braymer ostensibly to ask him “to check the specifications.” Any errors would then be his fault, not theirs. As far as the report itself was concerned, Keppler added that “our readers came first, not his desires.” Besides, a simple fact remained: “our readers wanted to know about the Questar.”[79]

Rather than draw his ire, Keppler and his colleagues won not only Braymer’s enthusiasm but also his friendship. Starting in September 1962, the month after its review of the Standard Questar appeared in Modern Photography, Braymer began advertising there regularly. In his first promotion appearing in that publication, he even used his advertising space to quote most of the concluding paragraph from Keppler and Sherman’s report.[80] With only a few gaps in an otherwise long and largely unbroken chain, his company would continue to promote the Questar telescope in Modern Photography until June 1981.

Lawrence and Marguerite Braymer’s advertisements in Modern Photography represented only a small fraction of their formidable marketing efforts.

Notes

1 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1956, 456.

2 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1956, 456.

3 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1956, 456.

4 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, December 1956, 98; Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, July 1964, 7.

5 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, December 1959, 132.

6 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, September 1960, 151.

7 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript.

8 Lawrence Braymer, “Wanted: A Tube,” Astounding Science Fiction, November 1945, 102, 104.

9 Lawrence Braymer, “Wanted: A Tube,” Astounding Science Fiction, November 1945, 109-110, 123.

10 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript.

11 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, May 1963, 188; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction, May 1963, 5.

12 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript.

13 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript.

14 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript.

15 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, May 1963, 188; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction, May 1963, 5.

16 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript.

17 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, October 1958, 21.

18 Lawrence Braymer, “Telescopic Photography” (unpublished manuscript, June 1960), typescript.

19 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1956, 456.

20 “Contax S,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Contax_S, accessed December 8, 2020; “Contax D VEB,” Mike’s Praktica / Pentacon Dresden Pages n.d., http://www.praktica-collector.de/092_Contax_D_VEB.htm, accessed December 18, 2022.

21 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, January 1957, 133.

22 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, September 1960, 151.

23 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, September 1960, 151.

24 “Contax S,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Contax_S, accessed December 18, 2022; “Zeiss Ikon,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Zeiss_Ikon, accessed December 18, 2022; “Pentacon,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Pentacon, accessed December 18, 2022.

25 “KW,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/KW, accessed December 19, 2022.

26 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, May 1956, 327.

27 “Praktica (1949),” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Praktica_(1949), accessed December 19, 2022.

28 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, January 1957, 133.

29 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, July 1962, inside front cover.

30 “Praktina,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Praktina, accessed December 18, 2022.

31 “Praktina FX (1953),” MikeEckman.com, November 14, 2017, https://www.mikeeckman.com/2017/11/praktina-fx-1953/, accessed December 8, 2020.

32 “Praktina,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Praktina, accessed December 18, 2022.

33 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, November 1960, 28.

34 Standard Camera Corporation, advertisement, Modern Photography, March 1957, 104, https://archive.org/details/sim_modern-photography_1957-03_21_3/page/104/mode/1up, accessed December 21, 2022; Standard Camera Corporation, advertisement, Modern Photography, February 1958, 123, https://archive.org/details/sim_modern-photography_1958-02_22_2/page/n124/mode/1up, accessed December 21, 2022; Standard Camera Corporation, advertisement, Modern Photography, November 1960, 5, https://archive.org/details/sim_modern-photography_1960-11_24_11/page/n4/mode/1up, accessed December 21, 2022.

35 “Praktina,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Praktina, accessed December 19, 2022; Alberto Taccheo, “Introduction to the Praktina System,” praktina.com, January 2022, http://www.praktina.com/h04_main.htm, accessed December 21, 2022; Herbert Keppler, “At Last: Praktina IIA 35mm Prism Reflex,” Modern Photography, December 1961, 130-131, https://archive.org/details/sim_modern-photography_1961-12_25_12/page/130/mode/2up, accessed December 27, 2022.

36 “Nikon F,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikon_F, accessed May 4, 2020.

37 “Praktina FX (1953),” MikeEckman.com, November 14, 2017, https://www.mikeeckman.com/2017/11/praktina-fx-1953/, accessed December 8, 2020.

38 Roger Hicks, A History of the 35mm Still Camera (London: Focal Press, 1984), 27-28.

39 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, September 1960, 151.

40 Online forum posting, Questar Users Group, July 20, 2008, https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Questar/conversations/messages/16868, accessed October 24, 2019.

41 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, May 1963, 188; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction, May 1963, 5.

42 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, February 1964, inside front cover; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, February 1964, 65; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Scientific American, February 1964, 26.

43 “Nikon F Camera with Mirror Releasing Button,” n.d.

44 Richard de Stoutz, “Nikon F with Mirror Pre-Release Modification,” n.d., https://www.destoutz.ch/typ_mirror_pre-release.html, accessed December 18, 2022.

45 “Joseph Ehrenreich, 65, Dead; Brought Nikon Camera Here,” New York Times, February 9, 1973, 27, https://www.nytimes.com/1973/02/09/archives/joseph-ehrenreich-65-dead-brought-nikon-camera-here.html, accessed MMMM DD, YYYY.

46 Matthew Lin, “Mirror-Up Modified Nikon F,” matthewlin.com, January 8, 2021, http://matthewlin.com/MyNikon/MirrorUp/MirrorUp.htm, accessed November 10, 2021.

47 Stephen Gandy, “Nikon F Variations,” cameraquest.com, November 26, 2003, https://cameraquest.com/nikonf.htm, accessed May 8, 2023

48 “Nikon F,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikon_F, accessed December 18, 2022; Stephen Gandy, “Nikon F Meters & Finders,” cameraquest.com, November 25, 2003, https://www.cameraquest.com/nfinder.htm, accessed December 18, 2022; Michael C. Liu, “Nikon F Metering Prisms and Meters,” mir.com, 1998, http://www.mir.com.my/rb/photography/hardwares/classics/michaeliu/cameras/nikonf/ffinders/fmeterprism.htm, accessed December 18, 2022; Peter Braczko, The Complete Nikon System: An Illustrated Equipment Guide (Rochester, NY: Silver Pixel Press, 2000), 53-57, https://archive.org/details/completenikonsys0000brac/, accessed December 19, 2022.

49 Questar Corporation, price catalog, April 1, 1966.

50 Questar Corporation, price catalog, October 1, 1968.

51 “Nikon F2,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikon_F2, accessed December 18, 2022; “Nikon F2,” Camera-Wiki.org, n.d., http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Nikon_F2, accessed December 18, 2022.

52 “Nikon F,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikon_F, accessed December 18, 2022.

53 Questar Corporation, Instruments and Accessories catalog, 1978 (second revision).

54 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, May 1954, 7.

55 Jim Perkins, “Questar Serial Number Systems” (unpublished manuscript, August 20, 2020), typescript.

56 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, October 1958, 21.

57 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, October 1958, 26; Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, November 1960, 26.

58 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, November 1960, 26.

59 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, November 1960, 26.

60 Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, October 1958, with addenda, June 1959, 28.

61 WASP Newsletter, volume 14 (December 1977), https://twudigital.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16283coll7/id/223, accessed December 11, 2020; “WASP Timeline,” wingsacrossamerica.us, n.d., http://www.wingsacrossamerica.us/wasp/resources/timeline.htm, accessed December 11, 2020; “Women Airforce Service Pilots,” Wikipedia, n.d., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_Airforce_Service_Pilots, accessed December 11, 2020; John B. Morrill et. al., “Hydrography of the Grand Canal and Heron Lagoon Waterways, Siesta Key, Florida” (Sarasota, Florida: Division of Natural Sciences, New College, 1974), http://www.sarasota.wateratlas.usf.edu/upload/documents/891_Hydrography%20of%20the%20Grand%20Canal%20and%20Heron%20Lagoon%20Waterways,%20Siesta%20Key,%20Florida.pdf, accessed March 26, 2020; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1957, 249.

62 Ralph F. Davis obituary, Sarasota Herald-Tribune, February 20, 2009, https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/heraldtribune/obituary.aspx?n=ralph-f-davis-bud&pid=124378648, accessed March 26, 2020.

63 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1957, 249; Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, November 1960, 28. In that booklet, Questar wrote, “Mr. and Mrs. Davis tell us that in their many years of Questar work, the Praktina camera has come to be their first choice, and has proved rugged and troublefree under hard usage.”

64 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1957, 249.

65 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1957, 486.

66 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1957, 249.

67 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, March 1957, 249.

68 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, August 1958, 532.

69 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Sky and Telescope, January 1959, 148.

70 Questar Corporation, advertisement, Natural History, August-September 1960, 4; Questar Corporation, Questar booklet, 1972, 15.

71 Dorothy and Ralph Davis, screech owl, Modern Photography, August 1962, 82.

72 Herbert Keppler and Bennett Sherman, “Questar: 1125mm of Lens Weighs 6.7 Lbs,” Modern Photography, August 1962, 94.

73 Herbert Keppler and Bennett Sherman, “Questar: 1125mm of Lens Weighs 6.7 Lbs,” Modern Photography, August 1962, 95.

74 Herbert Keppler and Bennett Sherman, “Questar: 1125mm of Lens Weighs 6.7 Lbs,” Modern Photography, August 1962, 95.

75 Herbert Keppler and Bennett Sherman, “Questar: 1125mm of Lens Weighs 6.7 Lbs,” Modern Photography, August 1962, 95.

76 Herbert Keppler and Bennett Sherman, “Questar: 1125mm of Lens Weighs 6.7 Lbs,” Modern Photography, August 1962, 95.

77 Herbert Keppler, untitled obituary for Lawrence Braymer, Modern Photography, March 1966, 82.

78 Herbert Keppler and Bennett Sherman, “Questar: 1125mm of Lens Weighs 6.7 Lbs,” Modern Photography, August 1962, 95; Herbert Keppler, untitled obituary for Lawrence Braymer, Modern Photography, March 1966, 82.

79 Herbert Keppler, untitled obituary for Lawrence Braymer, Modern Photography, March 1966, 82.

80 Herbert Keppler, untitled obituary for Lawrence Braymer, Modern Photography, March 1966, 82; Questar Corporation, advertisement, Modern Photography, September 1962, 96.